Rising Phoenix

I clicked the ferule of the pencil absentmindedly against my teeth - tick tick tick - then squeezed the eraser meatily between them, and stared at a blank spot above my head. Returning my attention to the small notebook in my lap, which was emblazoned with red metallic letters that read “I LOVE LISTS,” I made a quick calculation.

379

106

23 x 6

558

23

200

74

“Wow,” I thought, raising my eyebrows. “I made $1,478 last month on painting sales. And that’s just what I can remember.” I scribbled a few more figures and sat back again. “And…around $966 the month before. Hmm. What do you know? This is turning into a nice little side business.”

I dropped the pencil to my lap and pressed my fingertips into my eyes to ease a momentary stab of grief that, thankfully, left as quickly as it came. “Do you even know, Dad?” I said aloud to the empty room.

How Chinese Am I Really?

It’s only been three years since I picked up a Chinese brush for the first time. No, it’s even more amazing than that. Three years ago, I didn’t even know I could draw. The most artistic thing I had done was paint some cute cartoon-like winter scenes on glass balls I bought from Michael’s craft store and made them into Christmas tree ornaments for friends and relatives.

I met the man who would become my teacher, Bruce Iverson, at the local farmer’s market years ago and was instantly drawn to his beautiful Chinese artwork. There is definitely no one else around here - deep in New England - who does that kind of art. And from adolescence on, I’ve always had what I thought to be a far-fetched idea that I’d like to learn some Chinese calligraphy one day.

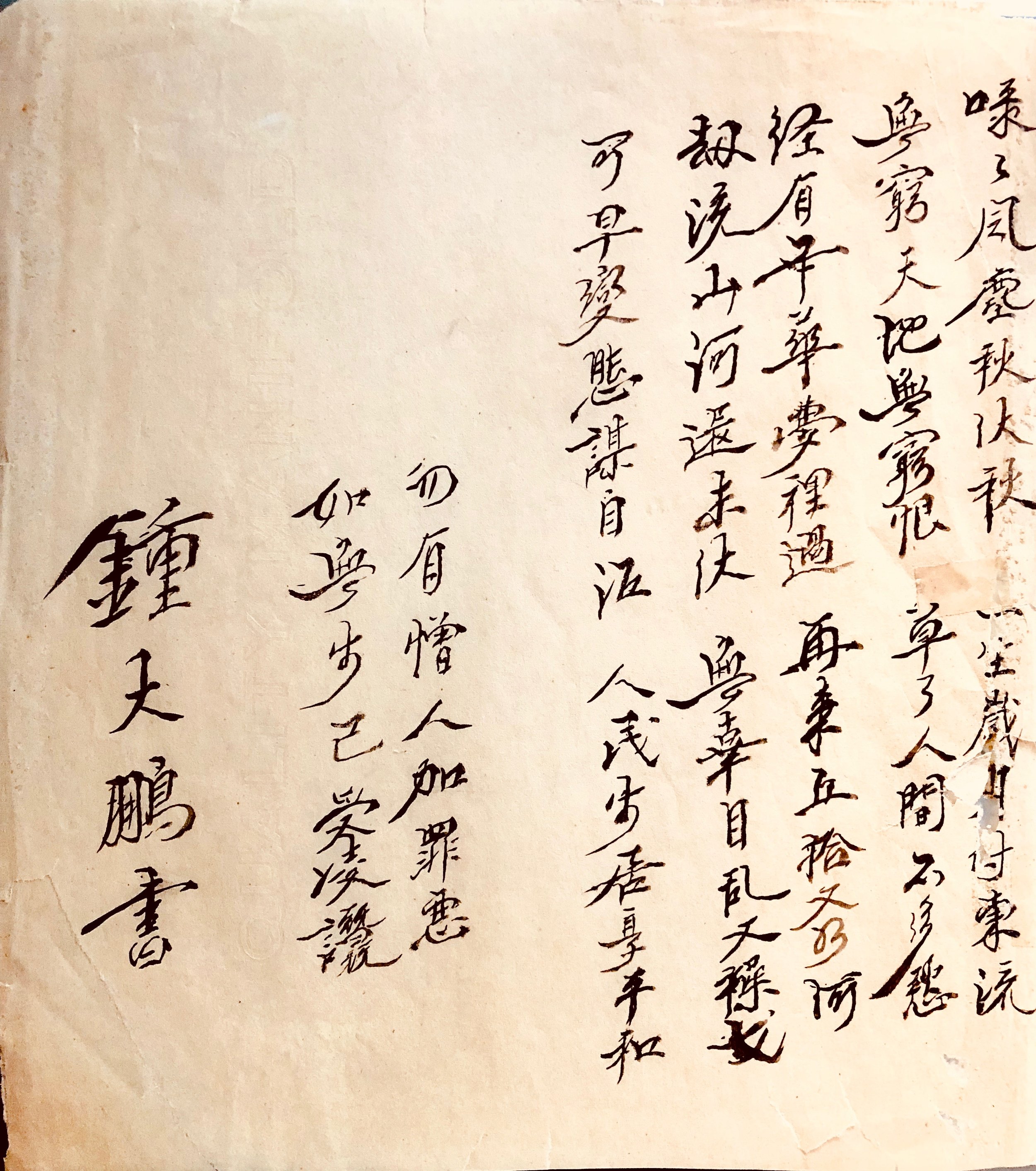

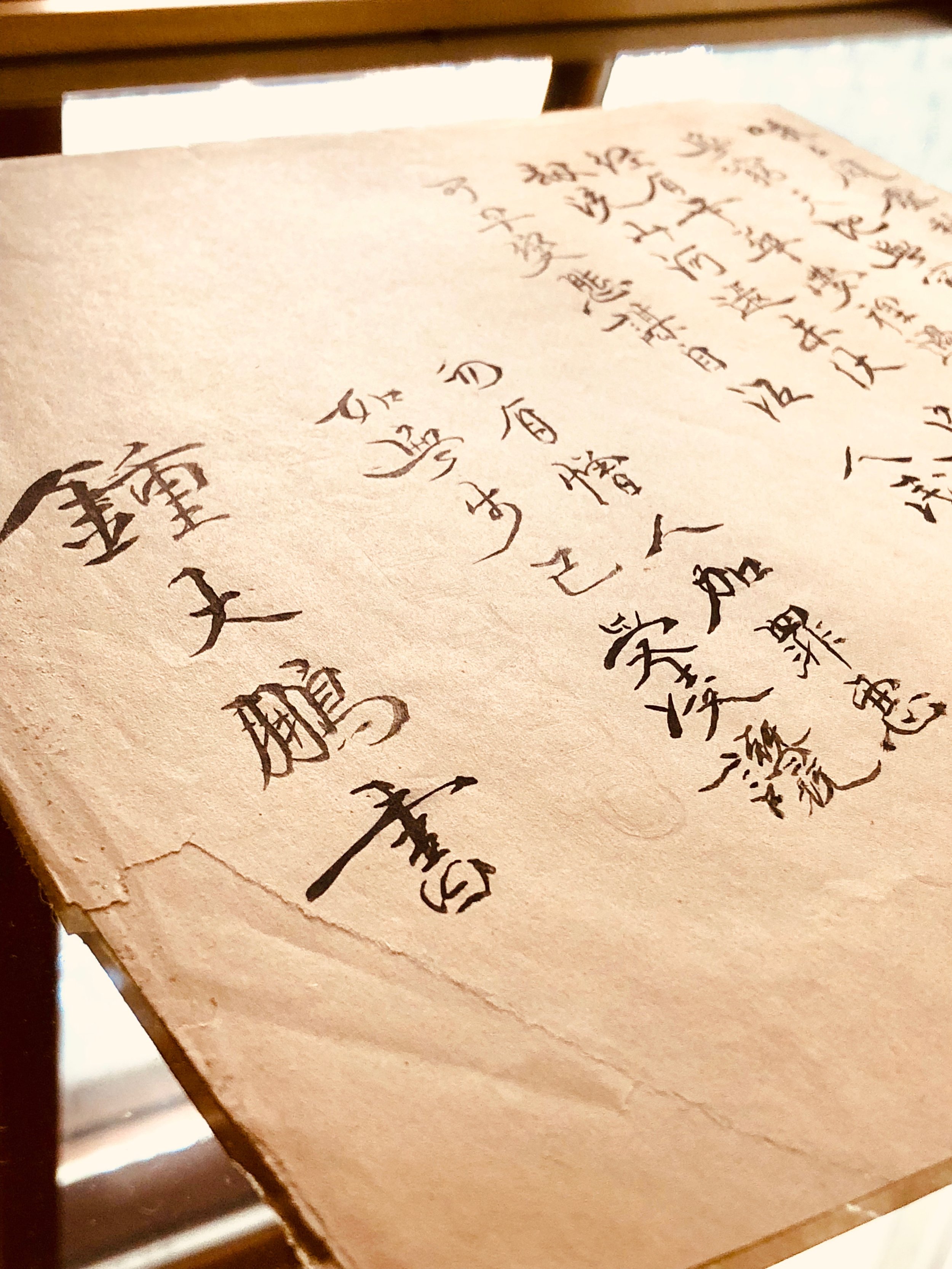

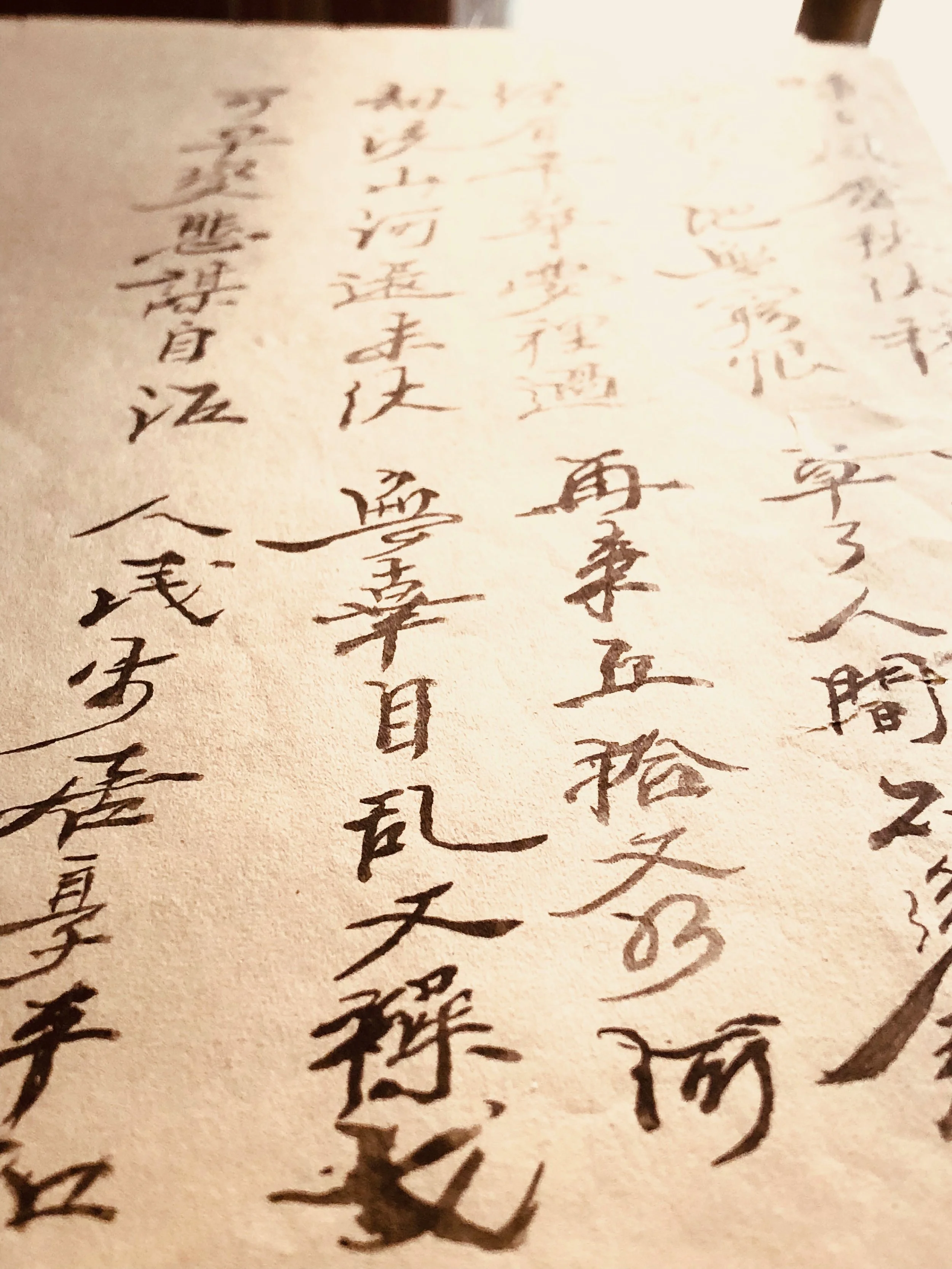

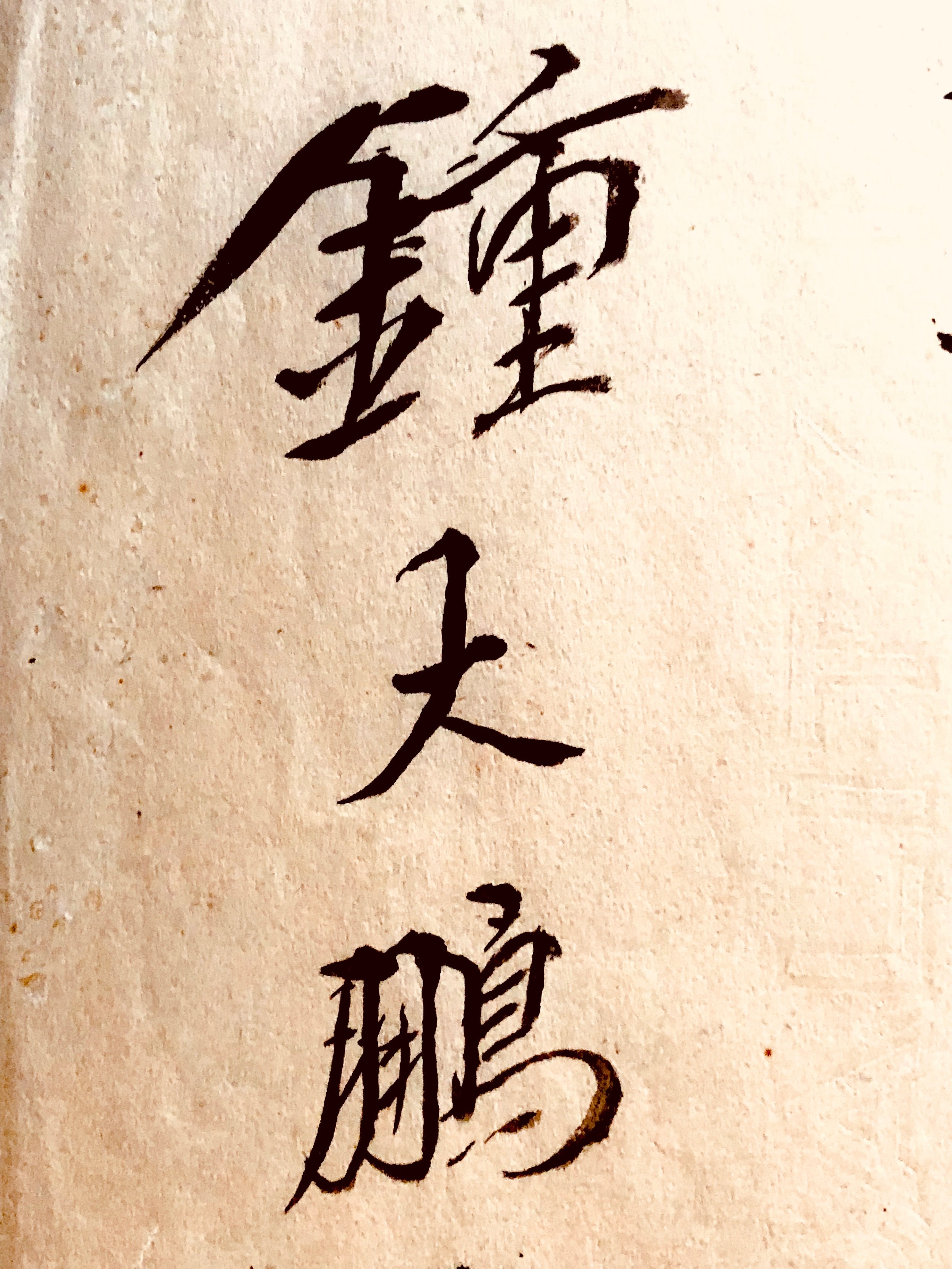

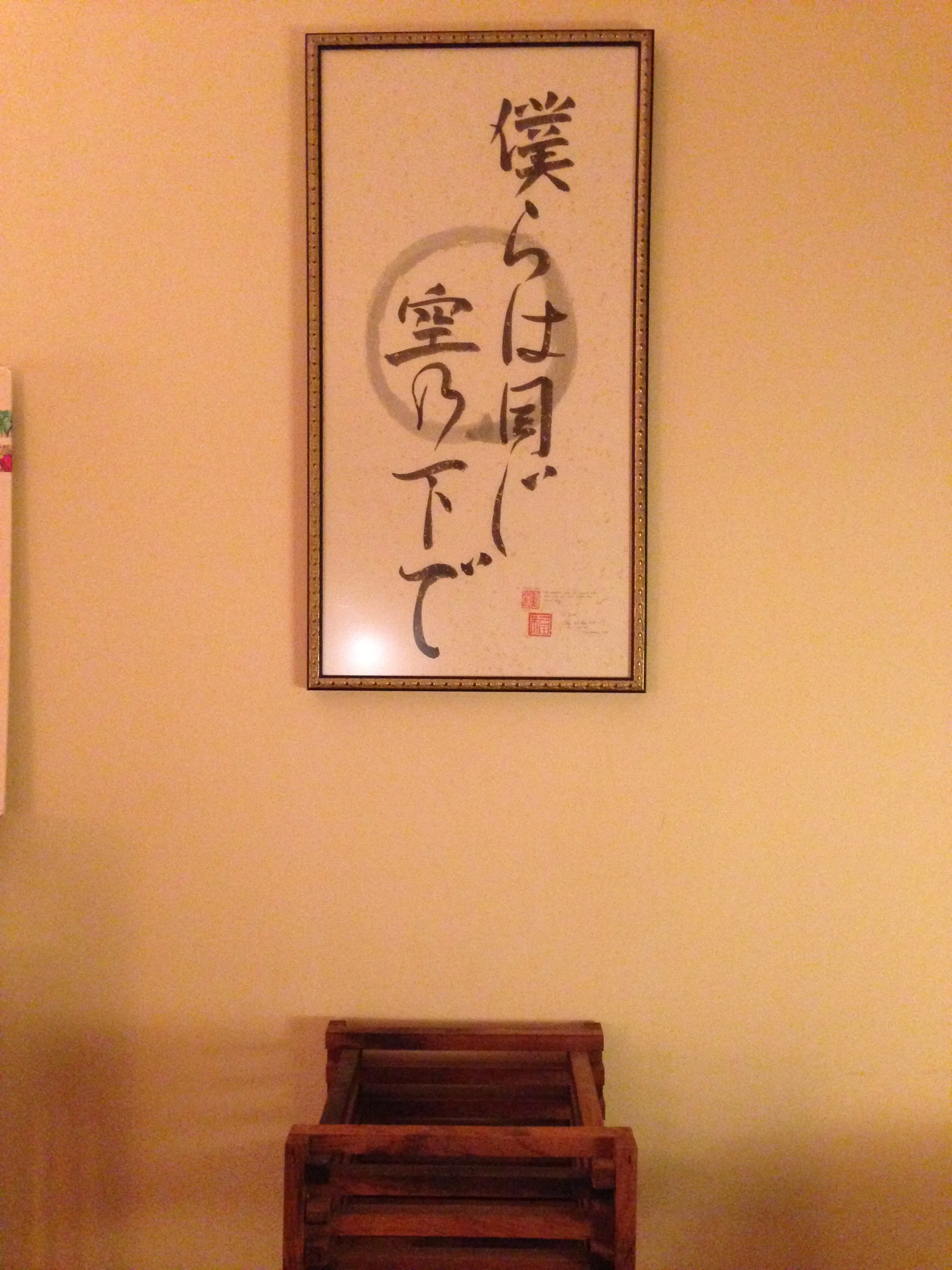

My “Grandpa Robbie,” as we called him in English, came from China and was reputedly a very elegant calligrapher. We have one of his poems on the thinnest, brittlest paper you can imagine. The spidery strokes and loops trickle down the page like water. Visually, you can appreciate his sense of balance and rhythm, his eye for composition on a page. I can’t read it, but I know that when Chinese people have seen it, their mouths have always fallen slightly open the longer they look at it. This makes me warm with pride, but also gives me the odd feeling of being left out because I’ll never be able to appreciate it on the level that they do.

“Your grandpa is so profound,” said one friend in grad school, in the cubicle office we shared. She was quite breathless with it, a tear glistening in the outer corner of her left eye. She was the first native-speaking Chinese person I had ever met and so I had shyly brought the poem in to the office one day to see if she could help me understand it. She struggled to translate it, for her English was functional, not fluent. And so, while I know now that it is a melancholic poem, written by an old man whose life did not turn out the way he had imagined, or even hoped, I cannot feel the poem the way a native speaker can. It cannot make me cry.

When I brought it to a Chinese couple I knew at the mall, the husband dropped the poem on the glass display case by the cash register and said firmly, “I think your grandpa is a very important person!” He told his wife to get her phone and try to “google him.”

“Ohhhh,” I thought, “you mean, like, a historically important person?!” I knew Grandpa had come to America in exile for his role in the revolution against the Empress Dowager Cixi, but it hadn’t occurred to me that he might actually be a footnote in history. I waited, interested but skeptical, while they searched. They didn’t turn anything up on him and I relaxed back into daily life.

I wasn’t disappointed. Far from it. There are many heroes who aren’t famous. It was enough to know that he was making waves with his poetry and penmanship 65 years after his death.

I am of partial Chinese ancestry, but like many people I’ve heard refer to themselves as, for example, “non-practicing” Catholics or Jews, my Chineseness is mostly aesthetic. I have a fondness for jade jewelry and the warm glow of a rice paper lamp. I love that I tan easily and only rarely have to shave. And then there’s the love of soup! I was at a Filippino friend’s house one day, and eagerly gobbled down a special soup they had prepared and asked for seconds. One of the old aunties in the house spoke something in Tagalog, causing everyone in the room to erupt in appreciative laughter, while they shoved another bowl at me. I looked to my friend for a translation. She said, “They say, ‘Of course she wants seconds. Chinese people love soup.’”

Is that so? I had no idea. I smiled a little sheepishly but then shrugged it off; if eating soup was wrong, then I didn’t want to be right. And if it made me Chinese, then so be it. How does it work with chili sauce? Because I love that too. You should try it on cucumbers.

Sometimes we go to Chinatown for dim sum and silly hats or to watch the Lion Dance at Chinese New Year, but on the spectrum of “tourist” to “native” we probably count as “informed tourists.”

What I loathe is self-promotion, and I seem to have picked up on - and passed to my children - a tacit, and classically Chinese, understanding that you don’t act a fool in public because you represent The Family. “You’re a Chan,” Dad would say. “Act like one.”

Welcoming Pines

At the farmer’s market that day in 2014, when I first met Bruce, I had a deep seated attraction to, and curiosity about, all things Chinese, but had spent a lifetime hovering on the margins, coming only into fleeting contact with my family history and traditions. The internal pull of Asian art, stumbled upon in a farmer’s market in New England, overcame my natural introversion in the public square. I approached Bruce’s stand like an entranced Teletubby and bought a framed picture of a sleeping cat, which reminded me of my Aunt GG and her cats, Miranda and Frodo, as well as little Ptah. I also signed up for his mailing list.

A full year passed and one spring night I found myself walking the three blocks to his “Welcoming Pines” home studio for my first work shop in Chinese calligraphy. A life-long dream was finally coming true. Stepping through the white metal screen door, and into the converted garage for the first time, my senses were bombarded with the unfamiliar familiar. I knew and didn’t know everything around me and there was no place else on earth I wanted to be at that moment. My spirit soared for reasons I could not quite articulate.

An old pool table that had been covered to make a large painting surface that the class could gather around took up the majority of the space. Narrow tables and shelves lined the perimeter of the room. To my right were brushes, the elegance of which I had never seen, a small violet-colored orchid, some whimsical bits of driftwood, and a little CD player that was issuing low, evocative strains from an erhu.

To my left were shelves and cubbyholes stuffed with rice paper rolls; a desk of sorts, wonderfully disheveled with stacks of books, cups of brushes, fanning themselves in a circle, and white ceramic paint dishes stacked in a tower. An easel faced the large central table, where Bruce would demonstrate techniques for us to copy. In the far right-hand corner, there was a utility sink with several slate ink stones on its edge, freshly rinsed and ready for use. Students already there were filling old plastic Chinese take-out containers with water to rinse their brushes. There was a slightly burnt smell in the air, too, which I could not identify at the time, but which I now know was the smell of Chinese ink.

At the end of that first 2-hour class, I walked out into the warm May evening, feeling as relaxed as if I had just emerged from a natural hot spring on one of Japan’s snow-covered hillsides. My limbs felt made of rubber and a warm sense of well-being was bubbling up from my belly. The ceaseless chatter of my “monkey mind” - alerting me to non-existent dangers, reminding me of my to-do lists, shoving worries in my face (“you haven’t forgotten THESE have you?!”) - was also, amazingly, silent.

I had no expectations for myself in signing up with Bruce, no aspirations beyond the simplest and most heart-felt desire to just “feel good.” At that point in my life it seemed to be the one thing I couldn’t do. Mom was gone, Dad was failing, and I felt helpless, hundreds of miles away. When I wasn’t loving my little boys, I was wretched. I needed an active intervention, a great disruptor, something that would shock my system with such newness that just in order to get my bearings, I would have no choice but to focus away from my now-habitual feelings of fear, grief and overwhelm.

Mythic Rare

“I need to do something for myself,” I told Brent one day. “Something that has no functional, earthly value except to delight me.” When I had turned 40 the year before, Brent had bought me piano lessons for that very reason; he also encouraged me at that point to take at least one day a week and “make it mine.” I may tease him about being a “Giant Sea Otter” - committed only to play and eating clams in a reclined position - but Brent is wiser than I sometimes want to admit about the difference between a “human doing” and a “human being.” He enthusiastically supported my taking calligraphy lessons and said he’d take care of the little guys’ dinner and bed time on those nights.

Well, I loved it. I went in wanting to feel good, and I came out feeling great. I signed up to learn some calligraphy, and went on to learn all kinds of Chinese brush painting methods, techniques and traditions. Every few months, when Bruce’s emails came around, I found another class I wanted to take - Iris; Bamboo; Birds, Bugs, and Beasts. I learned wash techniques, mounting techniques, uses of color, the effects of different media - wet brushes, dry brushes, practice paper, shuen paper, flat paper, crinkled paper. We read poems from the ancients and talked about some of the philosophies and traditions behind different painting styles. It was wonderful and although I didn’t feel that I showed any particular talent for it, it didn’t matter to me at all. I was proud of what I was doing and most importantly, I was having fun with other people - veterans, divorcees, widows, retirees - who, like me, were living proof that it’s never too late and never “the wrong time” to try something new.

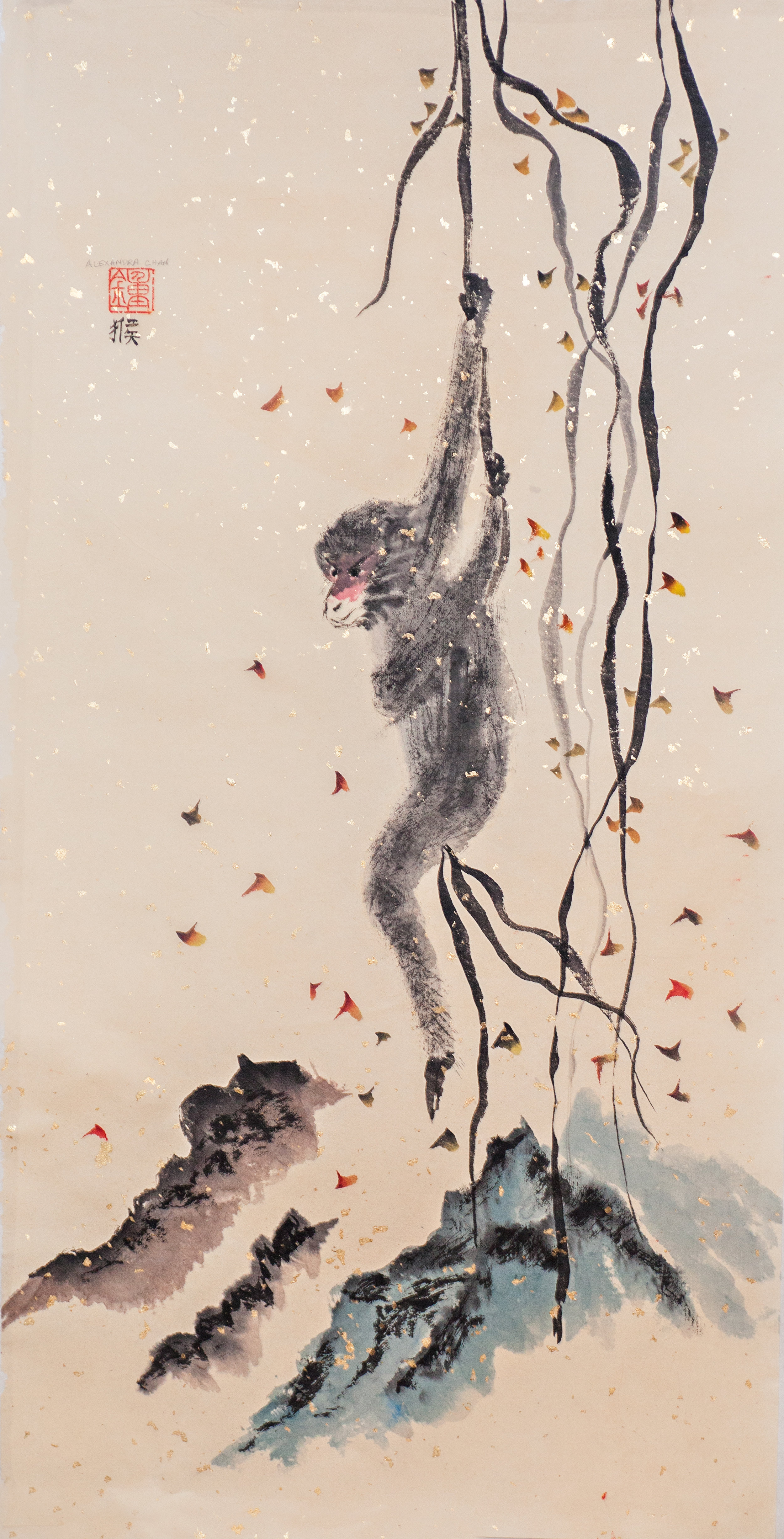

In between workshops, I practiced a lot. Bruce is spectacularly talented but his specialty is flowers and landscapes, while I felt a quickening at the animal energies. I watched YouTube videos and tried to paint along - fish, birds, pandas, amphibians, insects. And what I found was that in painting them, even poorly, I seemed to pick up elements of their energy in myself. This, it seemed, was the whole idea behind Chinese brush painting - that in the creation and contemplation of it, you can absorb and transmit certain universal energies.

Eventually I began to refer to it as “calling it in.” And different paintings will invite very different energies into your space. Through painting, I tapped in to my near-forgotten whimsy (panda); peaceful sure-footedness (heron); quiet power and equanimity in the face of danger (tiger); higher perspectives and clear sighted seizure of goals (eagle); feelings of optimism and rebirth (frog); perseverance (turtle); contentment (cat).

It was balm for my sad and weary heart. Sometimes I didn’t paint anything for months, and felt the sticky energies of fear and grief creep back in and take root, tainting everything. Then I went into a flurry of activity for weeks at at time and felt myself blessedly wash free of them - for a spell.

I liked to challenge myself and try to surpass my previous best. I often chose subject matter that was way above my skill level, but kept at it anyway, undeterred and unashamed. The harder it was, the “cleaner” I felt when I was done. It was its own reward. And eventually, my abilities did begin to rise to the task.

Once I shared a monkey swinging in vines that I was especially proud of with my friends on Facebook and received a private message from a Vietnamese acquaintance I hadn’t seen since we went to high school together. “Can I buy that monkey?” he asked. Incredulous, I responded that it was just something I was playing with, it wasn’t very refined, there seemed to be a little smudge on the paper, and it was irregular size and would be hard and/or expensive to frame. “I also don’t know how to back or mount it,” I wrote. I asked if I could do another one, better maybe, and to his size specifications. “No,” he said. “I want that one.” So I sold it to him. “Well, THAT just happened,” I thought. An Old World Asian saw my stuff and didn’t snicker up his sleeve, he asked to buy it. How about them apples?

As I got better control over the brush, I began to make little gifts, tucking a Chinese character (“love,” “joy,” or “tranquility,” for example) into my Christmas cards. For Dad’s 101st Christmas, I painted a calligraphy message on a long sheet of gold-fleck shuen paper and had it framed. “No matter the distance,” it said, “we are under one sky.” He hung it on his bedroom wall, where I could see it over his shoulder every time we FaceTimed. I also gave him some misshapen goldfish that were supposed to be swirling around each other in a bowl, which he received with equal admiration and gratitude. Dad was always my biggest fan and found outsized ways to express it.

“You should change your career,” he said, turning the mangled goldfish from side to side to see them from all the angles. I rolled my eyes.

Preposterous! I only just started a year ago! And had he forgotten so soon that I had quite recently, actually “changed my career” when I left 20 years of archaeology and “The Academy” to become a full-time photographer? “You’re probably the best photographer in the world,” he had said about that. I fumed in humiliation at the hyperbole. “I’m serious,” he had said. “You don’t believe me? You don’t trust my judgment?”

“No,” I thought, although I didn’t say it. He was pulling rank on me as the first professional photographer in the family. To argue with him on this point would, in some way, come across as impugning his expertise, so I had had to let it go. Listen, I had a dad who actually literally thought that I was the best cook, the best writer, the best photographer, the best parent (“perfect” I believe was the word he used, and without a hint of irony), and the most beautiful woman on earth.

These were not opinions to him, but facts in his world. And to be these things, not in the estimation of some hapless rube, but in the estimation of Colonel Robert Earl Chan, The Most Interesting Man in the World? How lucky am I? I tell you, sometimes you just have to know how to take a compliment and move on. I also wondered, if I weren’t all these things to him, where might I be today? Probably nowhere nearly as special.

Never underestimate what your faith in someone can empower them to do and to be.

One day, after I had taken several workshops with Bruce, Jin and I ran into him on one of our walks into town. Bruce was wearing cargo shorts and sandals with a windbreaker on and a worn and faded cloth baseball cap. We chatted on the sidewalk for a bit and then waved and went our separate ways.

“Who was that?” asked Jin. I pulled up with a jerk, while Jin kept walking; it hadn’t occurred to me until just then that my family had never had occasion to meet Bruce before.

“I thought you knew! That’s my brush painting teacher,” I said, trotting to catch up. Now Jin stopped dead in his tracks.

“That white guy is Bruce?!” he said with all the animation you’d expect from an 8 year old who’d just had his world rocked.

“Yeah,” I chuckled. “I never told you he was white?”

“No,” said Jin, “I imagined him looking like Grandpa, but with a topknot on his head and one of those stringy little mustaches and beards.”

“A ‘fu-manchu’,” I filled in for him.

“Yeah! I thought he’d be an old Chinese guy with a fu-manchu. Maybe some robes.” Not an unreasonable assumption, I suppose. I mean, his name is Bruce.

“Whoa,” he continued, reliving the moment of revelation, “Bruce is, like, mythic rare.”

“Mythic rare.” An ingenious use of language! I took it and tucked it away like a lucky charm, to bring out and remind myself at any time of things to be grateful for. To me, the entire experience of stumbling into Chinese brush painting the way that I had - exactly when I needed it and without knowing what I needed - was itself mythic rare.

The Alchemy of the Brush

About a year after this, I was topping 40mph on skis at the resort at Sunday River, in Maine, my lungs and thighs burning, when the phone in my breast pocket rang. The boys were in ski school. Thinking one of them could have had an accident, I grabbed my glove in my teeth and pulled my fingers free to unzip my coat and fetch the phone. “Hello?!” I yelled over the wind.

It was not the ski school, but Dad’s home care case manager. I pulled in at the base of the slope and practically ran out of my skis, heading for the lodge where I would be able to hear better. I made it through the door before needing to find a wall. I fell against it and slid un-self-consciously to the floor while ski boots clumped heavily all around me, in a whirl of color, this way and that, red, yellow, white, silver and blue. Dad had been put on home hospice and I should come home. Aware that I was sitting crumpled on the floor and crying openly into a phone in a high-traffic area, I felt a small voice try to assert itself for a moment, “You’re a Chan, act like one” but it was soon drowned out and swept away.

We drove through the night to get home, and when we arrived early the next morning, I was heartened to see Dad sitting up in bed and quite cogent, albeit with an oxygen tube up his nose, “strictly for comfort.” Maybe it’s not as bad as all that, I thought. And indeed we did have three wonderful days, where Dad rallied and remained interested, engaged, and amused by the boys.

They took turns enticing him with lemonade through a straw, and banana pancakes. “Open wide, Grandpa,” said Jin, flying the fork toward Dad’s mouth like an airplane. Dad followed instructions and made grunting sounds of pleasure at the old familiar taste. And then opened his mouth again expectantly. So unimaginably cute, those two. Jin, who was a pretty good reader at this point, also brought out the Frog and Toad books - which Dad had read to me when I was little, and I had read to them - and climbed into bed with Dad and read out loud to him. Dad laughed out loud at “The List” just like he always did, when Toad lost his to-do list to the wind and couldn’t run after it because, well, it wasn’t on the list.

When Jin and Seu had to return to NH to go back to school, I saw Dad fold in on himself. He had saved the best for his boys and now he had to rest. One day I was compulsively clearing some clutter by the bed, trying to stay active and busy, when he turned his head to me. The quiet hum of the oxygen machine whirred in the background.

“Hey, Honey,” he said, gasping a little. It took some effort to talk. “Why don’t you change your career and start selling those paintings you make?”

“Oh Dad,” I said, shaking my head, speechless. Not again. Not now. I would have thrown gasoline on all of my painting supplies and gladly see them burn at that point - the idea that I should have thought anything in the world could make me feel better was, I realized, pure farce. I was certain I would not survive this - not in any form recognizable to me. I was also deeply cognizant of the fact that this might be one of the last times I would ever be cheered on so faithfully in my life.

“Never underestimate what your faith in someone can empower them to do and to be.”

That was indeed the last lucid thing he said to me. He died in my arms three days later, the greatest cataclysm I have ever experienced and the most sacred gift I have ever received.

You don’t forget a parent’s final words to you. You put them in your pocket and rub them like a worry stone, this way and that, examining them from every angle. They take on depth, meaning and symbolism that you perhaps missed in the moment; whether good or bad, they are also like to sink in and become a personal mantra for you. You hear them day in and day out, over and over and over again, maybe for the rest of your life. Gradually, I was deeply sad to discover, I couldn’t hear his voice saying them anymore. Just the words remained, echoing. Start selling those paintings you make. Start selling those paintings.

Grinding the Ink - On the Meditation of Mortar and Pestle

It wasn’t a week before I was back home and wandered in a daze back into my painting studio, unwashed, ungroomed, and uncaring of much, but seeking relief of any kind. I swung my wooden drafting surface up to level and laid out the felt on top. I drew a tall stool up behind me and, dressed in loose-fitting, comfortable clothes, rested on the edge of the seat. Then I reached for the glass eyedropper of water, the ink stick, and the slate grinding stone. The tinkling of the dropper against the glass bottle was a merry sound that I appreciated. Tink, tink, tink.

Some people want to rush the grinding of the ink because they just want to get painting, but this is a mistake and you'll pay for it one way or another if you do not attend the grinding of the ink as you should. Your ink will be thin and weak, your painting or calligraphy sloppy-looking. Rather than thinking of it as something you have to get through, look forward to making your ink, as a time that you have permission to let go of all worries and frustrations, all to-do lists and deadlines. My sole purpose, for the moment, was simply to grind.

Chinese ink comes in the shape of a stick, composed of some mysterious recipe of charcoal and glue, which, when mixed with water, and ground in slow circles in a slate dish, turns first to a paste, and then finally into a smooth, silky and viscous liquid. As the ink began to form, the faint but sharp smell of charred wood rose in a little ribbon. I inhaled the ancient smell as far as it would go and relaxed further into my task.

I heard, but paid no attention to outside sounds - the muffled thuds and flops of three cat bodies tumbling playfully outside the door, street sounds through the window, the occasional phone ringing. While I sometimes, in such a meditative state, begin to contemplate the work I am about to create - the strokes and composition, the color, etc. - on this day, I contemplated nothing at all, and sank further into the blessed silence.

The intensity and depth of concentration required for Chinese calligraphy and brush painting makes the grinding of the ink much more than a simple preparation of materials. It is a form of meditation in its own right, and in undertaking it, you are also preparing your mind and body for the task to come. The artist prepares herself as she prepares her ink. It is said that in engaging in this process, or even in watching it from outside, one can gain a glimpse of the Tao.

I quickly learned that there was no other thing that alleviated my pain as well as Chinese brush painting and so, soon after Dad died, I began to paint with abandon. I bubbled with raw and ragged energy, but one's state of "flow" I learned (that is, one's level of immersion in a task, whatever it may be), is like a vessel. It is built to contain whatever you have to give it. So deep and so wide, in fact, that it can receive the whole of a broken heart, and even, through strange alchemy, create a joyful one.

Grief flowed into the brush, lightness and renewal flowed out.

“one’s state of ‘flow’ I learned (that is, one’s level of immersion in a task, whatever it may be), is like a vessel. It is built to contain whatever you have to give it.”

One day, I walked in to my studio defiant. I suppose I was in one of the “stages of grief.” I didn’t want “relief,” or “beauty” or “peace.” I was mad as hell and wanted my personal power back. I decided to paint a tiger.

To me, big cat energy is about quiet power and intensity; supreme competence matched with utter equanimity. There is no hysterical judging of a situation or task as either good or bad, possible or impossible. A tiger simply sees what needs to be done...and then does it. Imagine if I could see a life without Mom and Dad…and then live it? That’s the kind of power I was talking about. I wanted that kind of power.

What came of that session is now one of my best-sellers, “Tiger Lapping at a Stream” (video shown below). But when I painted the first one, in the weeks after Dad’s death, I made unintentional “eye contact” with the tiger and a peculiar thing happened. I felt the energy actually start to rise in me. The sinuous coil of his body, always at the ready.... Relaxed but never taking his eyes from the target. Of course, I had painted the thing myself, but somehow, even just looking at it, I felt those energies coiling in me. In the bottom corner, I added calligraphy for the old Asian proverb, “Fall down seven times, get up eight.” I walked out of the studio that day feeling a totally different person than when I had walked in. It was so stark, it could not be denied. There is Big Magic in there, I thought.

I found, over time, that Tiger energy is good for low vibrations of fear, loss, grief, fatigue or overwhelm. You don’t have to have lost a loved one to know what I’m talking about. The world today offers plenty of opportunity for these low vibrations to take root and make us feel like we can’t go on. But I also found I could call in tiger energy when I was taking on new, exciting but perhaps intimidating, endeavors: a new business, a new life milestone (marriage, parenthood, a new job, a big move). I found that I could tap into Tiger and he would let me know that I can and will succeed. And I couldn’t help but “feel good” about that (Music “Feelin’ Good” by Nina Simone below):

Calligraphy on the piece above, which I painted for a coffee shop downtown, reads “True victory is victory over oneself.” It’s about releasing limiting beliefs we have about ourselves that inadvertently keep us from getting what we truly want in this life.

After that first “tiger encounter,” I began to pay close attention to how different animal energies made me “feel” and started treating their creation and contemplation as Big Medicine for myself. Too serious? Getting down-trodden by estate settlement? Take two pandas and call me in the morning. Feeling lonely and disconnected from even your best friends and family? Nothing a little pig or a Dutch rabbit can’t help you out with. Does life seem too painful, the future yawning before you, colorless and tasting of ash? Make yourself infinitesimally small and take a journey on a sampan through a clouded gorge.

“My path is mine to me,” I wrote down the side of that one, “I treasure it and follow it to the end.” To me, that means that no person can walk our path for us, nor can we walk any path but our own. To fully step into the mantle of your own journey (fully inhabiting it, and without squawking, judging, wishing, sighing) is the highest calling one can answer, and the greatest form of respect we can give ourselves and the people and forces that gave us life in the first place. I found that this painting reminded me that no matter the steep cliff faces I may encounter, nor the mist that may cloud my path along the way, my path is my own and should be embraced for all that it brings me to.

By the way, have you ever “fallen” into a painting before? It’s fun. Try it with me now, in Sampans in a Clouded Gorge. Buckle your seatbelts:

Rising Phoenix

Another symbol that I found myself rallying around in those early days was that of a phoenix. Within hours of Dad’s death, I began to encounter phoenixes, in every manner conceivable - starting with a book that lay face down on the living room floor beneath his body bag. When the coroner’s office strapped Dad’s body to the gurney and then raised it up and rolled it out the front door, I saw the book and picked it up. It was an old collection of fairytales that I didn’t recognize, and smelled musty and sweet. How it got on the floor like that I do not know. On the cover was a phoenix rising to the heavens.

At the time, I thought immediately of Grandpa Robbie, whose real name was Dah P’eng, or Great Phoenix. In some inexplicable, grief-clouded way, the book with the phoenix on it, left for me while my father’s body was rolled out the front door, made me feel less alone - like it was a gentle reassurance of another presence by my side as well as a directive for myself to “rise from the ashes” and know and embrace the transformative power of fire (pain).

But then I began to encounter phoenixes everywhere - EVERYWHERE! In readings, on television, in poetry and paintings, in a library display case of porcelain, on textiles, and then one day a friend sent a picture of her son in costume for some show or another and what was he dressed as? I knew it before I knew it: a phoenix. Did I mention that I live in New England where the iconography of rustic cottages and boat and anchor themes reign supreme?

In the midst of all this, I also went to another of Bruce’s brush painting seminars and the first character we were to do - part of a larger piece - was none other than the character for P'eng, a large mythical bird from Chinese mythology and my Grandpa’s own name. A chill went through me.

The saying we were to paint was pengchengwanli ( 鵬程萬里,)- literally, "P'eng Carries You 10,000 Li," or more loosely, "Blessings for a bright/unlimited future." It is an appropriate gift for graduations, a new job, opening a new business, or for anyone who is experiencing a life transition (divorce, bereavement, etc.). P'eng symbolizes greatness - great accomplishments as well as great promise. The phoenix symbolizes the power of self-transformation, the ability to lose oneself completely, and rise again "from the ashes" of one's former self. In a literal sense, though, I could also interpret it so: my grandpa, the Great Phoenix, would carry me far. My embrace of the transformative power of pain would carry me far. I felt sure this message was for me, an auspicious blessing for a new venture.

For four months I did almost nothing but paint in this manner, and when I came up for air and to look around, I found myself nearly buried by my own production. It was well-rounded production, too, I noticed - large, medium and small works, numerous animal energies including the entire Chinese zodiac, scrolls and framed works, calligraphy of all kinds. “Not for nothing,” I said to Brent, “but it’s almost like the inventory of a small store.”

You should sell those paintings you’ve been making.

Gradually I began to see a new path, and an unexpected way forward, leading to a future self I hadn't imagined before.

No, I had never imagined such a future for me. But Dad had. My throat closed over the thought, indescribably moving, of my father, in his final days, taking me by the hand and inviting me to visualize a future without him. With his simple but profound statement - you should sell those paintings you've been making - he was drawing my attention away from the present moment and casting it into the future. He did it for me, because he knew that I could not. He knew that I looked ahead and saw nothing but darkness, festooned with pain. So he used his last strength to show me how it was done. In essence, he was “leaving the light on” for me so I could find my way in the dark when he was gone.

In July of 2016, I pressed “PUBLISH” on my new Chinese brush painting store, Rising Phoenix Arts, and burst into tears. I had no idea what I was doing. But the next morning, like magic, I had three orders waiting for me when I checked my email.

My path is mine to me.

The phoenix carries me 10,000 Li.

Dad, do you even know?

Like, Comment, Share!

Although the buttons below work, Squarespace is currently struggling with a bug that erases the tracking at random. Please don’t let low or no numbers shown deter you. Likes and shares still help boost my visibility, even if the numbers don’t stick around to show it. Thank you!