Why We Tell Stories

You could probably argue that every story is ultimately about the search for human connection …and the cost it extracted from you to get it. Every story is about whether you got what you wanted the most - or didn’t - and who you became in the process of trying.

I can sit here now and tell myself any number of things: “I used to see no way forward, but now I walk a lighted path. I used to be afraid, but now I know I can be brave. I used to think family was everything, but now I stand on my own two feet. I used to think I needed saving, but now I save myself.” There is a story - and a cost - to linking the first half of those sentences with the second. Am I willing to tell it? It seems I’ve been sitting on the fence about the matter. And the question today is, “Why?”

An Unexpected Journey

I was 20 years old and had never even been on a proper hike when I found myself trying to pack for seven weeks on a deserted island off the coast of Alaska. It was to be my first archaeological field school. My brand new purple hiker’s back pack gaped at me like some tubular gut parasite from the bed. Archaeologists, even and maybe especially, new ones know all about parasites in the field. It ain’t pretty, and I’ll admit, I was nervous. In the end, though, the only parasites we encountered there had nothing to do with the gut - they were just transparent and nearly invisible blood-sucking shrimp. Skinny dip in Alaskan waters at your own peril.

Mom had taught me how to roll my clothes to maximize the use of space, but I had been told to expect a year’s worth of weather (summer, fall, winter, and spring) within any given four-hour period up there; so I tried to find layers that could be mixed, matched, added and tossed aside at will. There would also be no laundry, however, or showers either for that matter, and we would be digging large excavation units by hand all day every day, toiling through mud to find clues to the ancient past. It wasn’t like I could pack for five days and simply recycle my outfits.

The other items I brought were loads of batteries to power my Walkman, several mixtapes, an optimistic little carry-on bottle of shampoo (just in case), and J.R.R. Tolkien’s Hobbit and Lord of the Rings series - all bound together in one immense tome, made gorgeous by the evocative painting of the dragon, Smaug, in gold filigree on the cover.

Around this same time, doctors had found proteins in Mom’s blood that would eventually turn into cancer and carry her away. Because there was only a 2 percent chance of that actually happening, however, my parents chose to keep the news to themselves. And so, although I didn’t know it yet, it was most fitting, in retrospect, to have packed the most famous hero’s journey ever written. For I was a Hobbit far from the Shire, and the wheels of my own fate had begun to turn. And little did I know that I, like Frodo before me, and Bilbo before him, would be a lot further “off the map” than a deserted island in Alaska before it was through.

At the end of the summer, I sat on the plane heading back home, and watched - as if through a periscope - my neighbors putting in drink orders and wrestling with their little Cheez-its and pretzel bags. I had just spent a summer living in a tent in the wilderness; digging our own latrine by hand. We slept to the sound of barking seals, and made a habit of observing a cadre of bald eagles overhead every day. We lugged supplies and a rescue beacon to the highest peak (which was NOT actually “high enough”) in case of tsunami, for we were right smack in the middle of the “Ring of Fire.” This is a hot spot in the Pacific basin for earthquakes and volcanic eruption, but it sounded like a dragon’s lair to me.

The world there had been soft - sand, mud, tundra, waves; mounded landscapes dotted with domed tents; sleeping bags, and soft bodies sitting shoulder to shoulder at meal times; sunrises and sunsets. Even the clouds were softer than anywhere else, often behaving more like liquid than vapor. I watched clouds pour over the top of our “mountain” one day, and glide down the slope like molasses, or maybe even a living organism. The only boundary in the whole world there was the curve of the island’s spit, which extended like a dancer’s arm into the sea.

In comparison, the surfaces and edges of the civilized world seemed impossibly hard, sterile, and obtuse - tray tables, overhead bins, door latches, seatbelts; floors, ceilings, windows, 90 degree angles everywhere. I felt…enclosed, jostled…and was overcome with a feeling that I wasn’t like these people anymore.

Something profound had happened to me and nobody could see it. I may have looked the same, but I wasn’t, and I never would be again. Alaska had given me more than just blood-sucking shrimp. It had given me “the bug.” I came home thirsty for life in a way I had never been before, and ever after, I only wanted to see, experience, learn, and do more. And so I found (or awakened?) the Seeker in me. It was the most important discovery I have ever made (and as an archaeologist, I’ve made a few), because without the Seeker, I’d have been long lost.

“You’ve got to stay curious,” Dad used to say. “Never stop learning, and you’ll always be okay.” Dad was a seeker too.

“That’s lucky,” I thought. “I love seeing new places and learning new things.” So between the ages of 20 and 42, I took the advice literally and did indeed see a lot more adventure, both at home and abroad, actively searching for the edge of my comfort zone, and thrilling when I bumped up against it. But have you figured out yet how I missed the real pearl in Dad’s advice?

It’s easy to be curious when you’re having fun.

Off the Map

Well, and so it was that, 22 years after my initial reentry into Civilization, I landed in a wilderness for the second time, but it was of a dark, different and most unwelcome sort.

Dad had just died, and Mom had been gone for almost five years herself - one of the 2%, winner of the ultimate Booby Prize. I stood at the edge of a world that I did not recognize, nor know how to navigate. The forbidding landscape of a life without parents felt every bit as harrowing as the goblin tunnels of Mordor. And the last thing I felt was curious.

In those early, grief-addled days I was inundated - saturated - with memories. I compulsively reviewed my parents’ lives, especially Dad’s, which played across the screen in my mind like a summer blockbuster. If you’ve been reading along on this blog, or if you were lucky enough to know the man yourself, you’ll know what I am talking about: youthful hijinks, street fights, war; chases, captures, escapes; undercover missions, deadly illness, ghosts; inventions, true love, miracles. Dad’s life had it all. Just hearing about it made a person feel a little bit more invincible, a little bit more destined for greatness themselves.

I wasn’t consciously aware at the time, but the way I rummaged through stories and memories now was not unlike the way I had rummaged through shirts, socks, and hiking gear before a big trip. The first thing I always did before embarking on a journey was to lay out my supplies, and check my pack, making certain that I would have the four essential components: protection from the elements, sustenance, entertainment, and a good map and compass.

But there were no roads to where I was going; I was fairly certain that I had no clothes for these howling winds; and the hunger - for belonging, connection, purpose, love - was killing. What “sustenance” could ever satiate that? If memories and stories were all I had left, were they enough? I felt orphaned and homeless; how would I ever get “back to the Shire”?

And worse, I didn’t even have a “Shire” anymore, or so I told myself. This journey would be an inward one - an imaginary one - and would require me to find that sense of home, contentment, safety, and belonging…somewhere inside myself, where the landscape was currently ravaged. There would be no shelter there. But could there?

I had an idea that my map and compass, such as they could be, might be found in stories, memories. And I knew that if I had a map and compass, they would inevitably lead me…”Somewhere.” Because that’s what maps and compasses do. And Somewhere was bound to be better than Here. So I - the grieving archaeologist - continued to sift.

In the Beginning was Story

The playwright, Catherine Anne Jones, wrote that “every story has a sacred dimension, not because of gods, but because a man or woman’s sense of self and her world is created through [it].” Stories link people to their past, orient them, establish their reality, give meaning and purpose, and influence direction. Stories also reveal and clarify something essential within ourselves and are a vehicle for sharing that hard-won wisdom with others, providing a mirror: “what would you have done? And? Then what?”

To feel another’s pain, joy, regret, shame, love, or grief, awakens empathy. It also validates our own experiences and makes us feel the simple connection of being human.

The science of storytelling shows that stories that resonate raise the level of oxytocin - the “love drug” - in our brains. Neuroscientists at Princeton went further to examine the “neural coupling” that occurs between speaker and listener during effective communication (such as a good story). They found that the speakers’ and listeners’ brains exhibited joint, temporarily coupled, response patterns to each event. The significance is that brains that undergo a joint experience are, by definition, “not alone.”

What they also found was that while facts light up the data processing areas of our brain, stories light up our sensory centers. In other words, when we hear stories, we are there. So, while it may seem obvious to say that stories evoke emotion and create a sense of togetherness or connection, science tells us that this is literally what is happening.

“Stories […] are the signal within the noise.”

Storytelling is so foundational to the life experience, in fact, that it may be the thing that actually makes us human - not “bipedalism,” not “toolmaking,” not “opposable thumbs.” Our brains are hard-wired to detect patterns - not just in visual forms, like reading facial expressions or distinguishing between the footprints of predator and prey, but also in sound and in information. Franke Rose writes that “stories are recognizable patterns, and in those patterns we find meaning. […] We use stories to make sense of our world and to share that understanding with others. They are the signal within the noise” (“The Art of Immersion: Why We Tell Stories,” emphasis added).

Stories have been shared in every known culture, back to the Caves of Lascaux and beyond. In fact, although I can’t prove it, I will stake a claim here, as a Ph.D. in archaeology, and with some measure of expertise in early human origins. I believe that when paleontologists found the first evidence of the controlled use of fire, dating to some 1,000,000 million years ago, what they were really finding was the first evidence of Story.

Fire extended the natural daylight into night for the first time, freeing our ancestors from the tyranny of sunset. It warmed them, expanding their geographical range. It protected them from predators because most animals, including the big ones, knew enough to fear fire, even if hungry. But one couldn’t stray far from the fire after dark, and so what did one do, sitting huddled around the burning wood with other members of one’s troupe? Why, I imagine they communicated in some fashion about the day - the things they had done and seen, the animals they had observed, the water and tubers they had found, the narrow escape they had made, the successful hunt they had had and what had made it so.

Story is one way to weave facts together and communicate them to others, but it also happens to be the most effective way to do this because, the evocation of emotion makes facts more likely to be retained. Again, science. That is, you were much more likely to remember how to get out of a scrape with a cave bear if you knew the story of how Uncle Droog got his bear claw necklace.

Past, Present, and Future

There is another aspect to story and memory to consider. While stories link us to our past, and give us a moral compass, they also allow us to project ourselves into possible futures. How can we know where we are headed, or where else we might want or need to go, if we don’t know who we are or where we have been? Stories fulfill that purpose. Indeed, studies have shown that amnesiacs not only forget the past, but also actually lose the ability to imagine the future, a topic explored to great effect in a documentary recently out called “Tell Me Who I Am.” It follows the story of one man who suffers from amnesia and who has become dependent on his twin brother’s stories about their lives and childhood together for his sense of self. The tension arises when he discovers that the stories are all fabricated to hide dark family secrets. The amnesiac loses his past for a second time, and finds as a result, that he simply cannot move forward. We find that memory allows us to exist, and allows us to imagine a future. With it, we can feel that our lives have meant something, and if we are lucky, that we still have important work to do. Without it, we are lost at sea.

So if I found myself “living in the past” a lot after my parents died, I make no apologies. I was looking for the path forward.

Picking up the Pieces

When I was a teenager, banging out the front door to go hang out late with my friends, Dad would always call after me, “I’ll leave the light on for you, honey. If you need anything, call. We’ll come and get you.”

I imagined him now, quite clearly, walking just ahead of me, a shadowy figure holding a lantern high, and casting a circle of light at my feet - the light of his own life and example. I could feel Mom further up the path ahead, less visible, but a quiet, reassuring presence nonetheless - a place to get to. I need only follow their lead. I searched my mind for any crumb, any clue. Who knew which rock overturned might reveal the way out?

And so it was, lost in a jungle of grief, that I remembered a time when Dad had been lost - in a jungle in Burma - when he also did not know what to do or how to get out. Do you remember the story as told in Small Wonders? A friend who had gone ahead to scout several days before, turned up just in the nick of time, appearing far on down the trail. He beckoned Dad silently from each bend or fork in the path, as if to say “this way, come, follow me.” Dad had followed his friend’s signals like that all day long, leading his men to safety, and evading the Japanese ambush he had received intelligence was somewhere in the vicinity. But what he found at the end of the trail was his friend’s corpse, and a level of decomposition indicating that he had been dead for several days.

Maybe it wasn’t foolish to think there was otherworldly help to be had, when life has brought you to your knees or put you in grave danger. I sent a hopeful plea to my parents to not leave me alone and unaided in this dark wood. And indeed, in the last three years, I have glimpsed them both ahead of me on the trail, showing me the way - at least, in a metaphorical sense.

But it wasn’t just the stories that had gripped my imagination, and are a big part of this blog; I also had hundreds of war letters, and a box full of negatives from a life lived to the hilt. I had some personal musings, witty, clever and deep, scribbled into a pocket notebook. I instinctively knew that, in these sources, there was a template for many, and I was struck with the notion that this man - “Dad” - was not just for me. Soon after his death, I became obsessed with the idea of writing a book that would bring his wit, wisdom, clarity of purpose and, let’s not forget, bold, brash, swashbuckling badassery to the world.

The Problem - Whys and Wherefores

It would not be my first book. In 2007 I wrote Slavery in the Age of Reason: Archaeology at a New England Farm (University of Tennessee Press) based on my years of excavation at the Isaac Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford, MA. It was a labor of love and reviewed as “a beautifully written work of considerable ambition, intense curiosity and admirable inter-disciplinarity,” as well as a “work of real historical significance.” It is one of the offerings I am most proud of bringing out into the world. Professionally, it made my career and reputation and if you want to get an advanced degree in Historical Archaeology, or Atlantic and Global Studies, even as far away as in Germany, you have to know my work. That means something to me. A friend recently sent me a picture of my book on display - behind glass - at the Harvard Law School Library. That means something to me too.

But this...this was an entirely different animal. It would be the most vulnerable thing I had ever done. And worse, I couldn’t get clear on “what” - exactly - it was that I was trying to do. My primary sources were prodigious, but my mind buckled at all attempts to fit them together and present them in a coherent way. What would be the “story” I was trying to tell with all these hundreds of letters, pictures and parables? What would be the “signal within the noise”?

The obsession burned like fire; it was hot, hard to handle, and consumed me. This was no navel-gazing fever-dream I was in. It didn’t come out of nowhere. There is backstory to this; the post I called The Most Interesting Man in the World recounts the origin story for this lifelong dream of writing a book about Dad. His death simply felt like a call to action after a lifetime of consideration. Walking home by myself one night, after dark, I was overcome by the call and swooned into a fence where I heaved and sobbed the weighty burn of it into a clump of ivy. Another time, sitting in a pool of sunshine with a wise and much older friend, I choked up over a harvest salad, and she said “well, you have to write it; that much is clear. You are pregnant with it.” She could feel the “bulge” of it in the ether above me - a presence, looming, ready to burst. But still it wouldn’t come.

If the book is a tapestry, and I think it will be, I started Chan’s Peking Kitchen as a place to start collecting the threads I wanted to see woven into it. The essays in this blog all touch on some part of what I want the book to be. And while the blog is not the book, it is also not NOT the book, if you know what I mean. Here is where I explore different themes and experiment with subject matter as well as narrative styles to figure out what resonates, what feels extraneous, what works and what doesn’t. It has also been a place of extraordinary healing for me. I wrote my way out of the despair of becoming orphaned. If nothing else, this blog is a detailed narrative of my road to wellness, and that, my friends, is a lot more than nothing.

But can’t it become more than that? Because I haven’t given up on my dream.

In my writer’s notebook, I asked myself the question one day, “So you want to write a book about Dad. What do you want out of this? And why?” I wrote the following in response:

I want to create something tangible that reflects what I feel inside about Dad. I want to make the world see and feel what I see and feel. I want to write a best-seller. Why? Because Dad’s life and deeds are transcendent, I know they contain multitudes and depths for many. I want to see, touch, smell, carry an object that is a physical manifestation of the beauty I see inside. I want the process of creating this chef d’oevre to resurrect the man - for all intents and purposes - because his soul will feel present to anyone who reads it. I want catharsis and connection (the catharsis in me will connect and elicit catharsis in you). I want Dad to be a magnificent, inimitable and inspiring figure, but through strange alchemy, abstracted enough to the idea of “Father” that in the minds of my readers, he could be their father, their colossus.

I was pleased with what I had written, and felt that it gave me the beginnings of a map forward. But while I am grateful for the courage and purpose it gave me in the beginning - I could not have started a blog without it - I soon found myself spinning my wheels, and the reason is clear: my statement consists almost exclusively of surface-level whys. Sure, there was a little bit of a “deeper why” there - catharsis, connection - but for the most part, reading it now, I see only a young woman in existential crisis, grasping desperately at something that is slipping through her fingers like sand, and using the idea of the book to try to shore it up. That something - whatever it turned out to be, and I had work to do to find it - would be the Deepest Why of all. And I was beginning to suspect that it wasn’t even the right why. This is a problem, because as long as I continue to write from anyplace but the right one, I am never going to get where I need to go.

What I’ve come up against is a reckoning: that I have been trying to tell the “wrong” story because I’ve only partially unpacked the whys and wherefores of my needing to do it. Did I even have a point, beyond “Hey, look at me! I’m the daughter of a great man”??? No one wants to read that story. And what does it say about me, if I need to tell it?

Hmmm, good question!

Building a Narrative Arc

A good story must track a journey, and present a driving problem for the protagonist that cannot be opted out of and that is painful or consequential enough to force the protagonist to make internal changes. Usually that problem is a deep-seated desire that some internal, limiting belief of the protagonist herself makes impossible for her to obtain. Will she figure it out or won’t she? What will she be asked to give up to get it? The stakes must get higher as the story progresses; the protagonist must be hindered by fundamental misbeliefs that threaten to keep her stagnant and stuck; the “aha moment,” when it comes - and it must - has to be earned, and come at real emotional cost. Story is not story without struggle and growth. The narrative arc must track a “state of becoming” that is not, however, guaranteed. Those are the stakes.

Take as an example the fictionalized account of true events I wrote in “The Third Rail,” where I explored the origin story of Dad’s own “fundamental misbelief.” This was the driving problem that shaped a lot of what he did or didn’t do, accomplished or failed to accomplish, in life. It gave rise to a narrative arc I saw as going from “control” into “command,” and it went a little something like this:

A mixed-race boy in the Jim Crow South thinks he must be twice as good as anyone else to get half the love. This unspoken anxiety creates a compulsion to control the world around him and his own destiny. He proceeds to spend the next 100 years bending the world to his will, attaining impressive achievements, and conducting shocking feats of derring-do that lead many to remember him as “almost magic.” Moral injury in war contributes to existing feelings of unworthiness, and destroys his relationship with his son who has his own misbeliefs. Ultimately, he discovers on his death bed that control is an illusion, he must let go of grudges and disappointments, and accept that he has been worthy all along. He reconciles with the youngest child, lets go the need to with the oldest, and deepens his connection with the middle. He crosses the threshold from control into command and soon thereafter releases himself to death.

The problem was that I couldn’t figure out a way to convey the emotional cost of my own arc, which mirrored Dad’s in its travel from control into command, without at least alluding to certain truths that might cause collateral damage to living people. I don’t want to hurt feelings, or make hard relationships harder. I am also undeniably touchy and protective about anything that might lay bare some of Dad’s own frailties and failures.

The realization of the latter - that I am mythologizing my family by refusing to speak hard truths - has been most vexing to me for I defiantly wrote in my journal that I DID NOT want to write an account that deified Dad or the Chan family, or to present one-dimensional characters that are hard to love in any realistic way. I recalled my Aunt GG’s own colorful words on the subject: “Our [family] lacked none of the faults that other families display: pettiness, gossip, criticism, coldness, misunderstandings, downright lies…..” (from a letter written in 1995).

I am also committed to the idea that the characters that uplift and give the most hope to the widest audience are the ones who achieve greatness despite themselves in some way. And I want readers to soar upon reading the last page, called to their own highest potential. In theory, the Chans were perfectly designed to effect this. Plenty of pettiness, tragedy, betrayal and lies within our ranks; plenty of magic, redemption and greatness.

Yet here I am, obstinately refusing to “go there” in order to tell the story of my own personal transformation. The obvious question is, whatever I might proclaim publicly, do I secretly need a legendary family to feel worthy of love and admiration? Why is that? And if true, is it any wonder that I haven’t been able to get past a certain point on this project? The basic proposition is ill-conceived; no work that is meant to go out into the world to help others shift and awaken can be infected by Ego.

So my work of late has been to get to the bottom of this misbelief I have been laboring under (that I need a mythic family to be seen and admired, and that my value lies primarily in how closely I can demonstrate my connection to them). To identify this false knowing, trace it to its origin, and then to release or to integrate it, so that I can get on with the business of telling the story I was meant to tell is “the work” for me now.

So how did I come to over-identify so thoroughly with my family, and my father in particular, that when he died and “the family” fell apart, it constituted total existential crisis? Where along the way did I lose so much faith in my own self that the only way to exist, let alone be worthy, seemed to be to write a book, spinning mythic tales of a legendary past belonging to a golden family that only half-existed, and therefore could never wholly be written? Well I have a couple of ideas and one of them started…

Up a Tree

We were visiting my Aunt GG’s house in Savannah, GA, as we did every summer and I was having a sleepover of my own while there. Oh joy! My cousin, Chan’s, girlfriend at the time had two kids, Tammy and Eric, whom she would bring around to play with me when we were in town, and tonight they were having a sleepover with me. Tammy was probably about a year older than I, maybe two, with strawberry blonde waves, a freckled nose and a bright and sassy temperament that I found irresistible. She did all kinds of things I was too afraid to do, and it thrilled me.

Tammy was a free spirit. She liked to sneakily slide down the banister even when GG had told her not to. The precocious child of a single mom, she more or less did what she wanted, and when I think of her, she is always running around in circles, laughing, conspiring, thumbing her nose. What she thought of me, I really don’t know, but I considered her to be one of my best friends.

So when Tammy shook me awake in the dead of night during our sleepover, and beckoned me from my sleeping bag on the floor, I rubbed my eyes groggily and I followed. It was dark, the whole house was sleeping, and I could only just make out the glow of her white night gown slipping silently down the stairs in front of me. She stopped at the squeaky stair and turned to look at me over her shoulder, with a finger to her lips. Carefully skipping that stair, she led me to the front door and started fiddling with the lock, causing alarm bells to go off in my head.

“Ummm, I don’t think we’re supposed to go out there,” I said, louder than I had intended.

“Shhh!” she said. “Don’t be a party-pooper. You said yourself you like to climb trees!”

“Not in the middle of the night!” I said, flummoxed. The lock clicked and she turned the doorknob, pulling the door a crack open. I felt the humid air of a Georgia summer seep in and hit my bare toes, which curled into the wood of the floor as if to anchor me there. “You can’t do that,” I cried, getting desperate. “I’m…I’m telling!”

“You better not,” she said, closing the door and giving me a look that made me drop that option immediately.

And so out we went, down a further set of stairs to the street level and over to the tree that shaded GG’s second-floor porch. Tiny pebbles stuck to my feet, which I continually brushed off on the opposite calf. I looked nervously around me, up and down the dark, cobbled street. All was quiet. I gave Tammy a leg up to the first branch. From there, she scrabbled right up to the top and leaned way out, her bare feet against the trunk to steady hersef and peered avidly through the windows, which were now at eye level. She called down, “I can see everything from up here!”

She came down and then gave me a leg up. I actually did like to climb trees. This was the biggest tree I had climbed, and since there was no point to doing it unless I went up high enough to peek in the windows, that’s what I did. It didn’t seem nearly so scary as I had imagined, until I turned to come back down and found that I couldn’t.

Tammy stamped her feet on the earth far below me and whisper-shouted at me to come on, cut it out and just do it. The mortification of disappointing her forced me down a branch or two, but I soon realized that I was well and truly stuck. The next branch was too far, and I wasn’t strong enough. I was terrified, shaking, dizzy, and also deeply embarrassed. What a party-pooper! And then came the tears, which made it worse. “Go get help,” I wailed.

Tammy was beside herself. “NO WAY!” she said, “You’re going to get us in so much trouble! Just climb down!”

“I caaaaaaaan’t! I can’t do it, I don’t know how, I’m going to fall! Help! HELP MEEEEEE!”

“Oh my god. SHHHHHHH! Be quiet!” Finally admitting defeat, she turned on her heel and stomped up the stairs to GG’s front door. She shook her head at me in disgust before she flounced through the front door and, presumably, went to wake the adults.

Within a minute or two the lights started coming on and I could hear the commotion coming toward the door as adults tripped over each other to come see what was going on. The door yanked open, and a blessed yellow glow fell on my face from the hall light, dispersing the dark. There was Dad, first in confusion and alarm, looking this way and that. Then, having located me in his sights, his body relaxed and his face broke into a bubbling mirth. He walked to the banister at the front edge of the second-floor porch and found himself eye-to-eye with his six-year-old daughter, perched in a tree. Like a possum.

“Oh. There you are. What’s the matter, you can’t get down?” he said. Relief flooded my veins. I shook my head. I don’t remember exactly how the rescue happened. I think there was some noisy rummaging in the street-level basement, and a ladder involved, possibly some mild shouting among adults over best practices. Tammy defended herself in the background, “Okaa-ay! I’m sorry! How was I supposed to know she can’t climb trees?!” And our friendship was never really the same again after that.

Don’t trust yourself to take risks, I learned that day. You’ll only get yourself and others into trouble, and if you screw up they might not like you anymore.

The Fat Alaskan Indian and Special Ed

I was born with a rich fantasy life and vivid imagination that frequently carried me right out of this world (and which, I might add, now invites others to the same through my writing, my photography, and my art). So it is one of the treasured gifts I have received from my childhood self. To my peers and in the early years, however, it might have made me a little dreamy and inscrutable, and therefore an object of curiosity and/or derision. Up until I was about nine or ten, I was pure and innocent about it. I steeped myself in small pleasures all day without questioning whether I was worthy of them. I was already keenly aware of being “a Chan,” too, as if that’s all a person ever had to be. I felt that it set us apart somehow, made us a little bit special. And you can’t really blame me; “old Chan magic” is a real thing; nobody is immune (see Small Wonders). I was still very connected to this inner “bigness," because as a last-minute second chance for both of my parents, I was, at home, precious, extraordinary, and uniquely delightful. I had never experienced anything different.

Mom and Dad let me know in many ways that I was beautiful to them, supplying me with their attention and presence, meaningful compliments, encouragement, and, importantly, a number of ethnically ambiguous dolls. My eyes lit up with those because I saw how beautiful they were and could not help but see myself in them. I never cut my hair because beautiful girls had long hair, like my dolls, I thought. So my hair hung around my hips in disheveled strands because, while I loved to play with dolls, I was also irrepressibly curious and spent a good portion of my time crawling up trees (ones I knew how to get down from) and building forts in the underbrush. Baths were definitely boring.

I loved worms, mud pies, burritos and plenty of ice cream. I had favorite clothes that rarely had to do with whether they fit or were in style or not. Usually it was just the red or purple color I loved, the flouncy ruffle, or because Mom had put butterfly or rainbow patches on the knees to cover the holes. I was a sucker for pearlescent buttons and all things satin and velour. These little details, seen only for themselves, sparked such joy in me when I wore them that I pulled up sharply the first time I overheard myself described at school as “a walking garage sale.”

And then there was Karl Hauser (names have been changed to protect the guilty), the boy I had had a secret crush on since 1st grade because he was the class clown. He was bombastic and in your face and made me feel inexplicably lame, but I was drawn to it regardless. I hated my shyness and had always hovered longingly in proximity to those I perceived to be more socially adept than I.

I came upon him and a group of our classmates at the school library one day. His back was to me and I thought about scuttling around back of the group to slip out the door unnoticed, but then I did a surprising thing. With my innards churning, I stopped and said hello.

In fourth grade a group of advanced students had been separated out from our classes for an “extended studies program,” or ESP as it was called. The students in it joked that the acronym stood for Especially Smart People, and as a serious student with excellent grades, I expected to be part of this group. But I wasn’t, and it felt like the End of Everything. I was inconsolable at home, which eventually convinced my parents - not normally ones to intervene - to go to the school for feedback on why I wasn’t selected and whether there was anything I could do to be selected next time. They came back with the message: my grades weren’t the problem; my social skills were. And so Dad embarked on a year-long coaching regimen with me. He knew that while you can’t change a person’s character, you can do a lot to change behavior, and a shy person can learn to pretend she is not so shy as she really is. I’m pretending to this day!

“The first thing you’ve got to do is learn to say ‘hello,’ Honey” he said. “And make sure you look them in the eye when you say it,” he said, demonstrating a friendly level-eyed gaze, which was the default look on his face anyway. He made it look so easy. “And if you really want to make an impression, use their name. Don’t just say, ‘Hi.’ Say, ‘Hi, Jack! Hi, Sally!’ People will remember and like you better if you use their names. It’s just human nature.” So I spent the whole of 4th Grade walking to school, staring at my feet and talking to myself, “Good MORNING, Mrs. Edgar! How are YOU today? Good MORNING, Mrs. Edgar!” Then I forced myself to lift my face up and give a wide smile to the air in front of me. “I’m fine, thank you, how are YOU? Good MORNING, Mrs. Edgar!”

And do you know what happened next? A miracle! At the end of 4th Grade, on the basis of my “remarkable progress” that year in interacting with my teachers and classmates, I was admitted to the Extended Studies Program. It had worked! I had set my mind to something and done it! It was empowering.

So, this was why I had gathered up the nerve to override my flight response in the library and say hello to Karl Hauser and his friends (who were not, by the way, part of ESP). But my confidence was new and fragile, and the seconds dripped like centuries while my words hung in the air like doom. Karl turned around, his face lit up as if he was glad to see me, and for a second I thought it had worked. But then just like that, and without missing a beat, he said, “Oh look! It’s the fat Alaskan Indian! Here for more books?” For the record, I am neither Alaskan nor Native; this was a coarse play on the sound of my name (a-LESH-ka, Alaska…) and a nod to my waste-length black hair and tan skin. It also took my proudest accomplishment of getting into ESP and made it feel shameful. Don’t shine too bright, I learned. It’s unbecoming.

My stomach flipped and the blood turned to ice in my veins. For a moment I couldn’t hear through the rushing in my ears, but I could see the others laughing. I was suddenly acutely aware of the too-small turtleneck I had on. I was ashamed of the pretty little strawberries all over it and my lavender suede Nikes. And then, I did what the only instinct I had left told me to do: I laughed along with them, when really I was dying inside. Fat Alaskan Indian. Good one.

Anyway, and then to add insult to injury, I found myself sitting on the bus one afternoon soon thereafter that would take us to the Highschool for swim class. I stared out the window in a peaceful reverie, tracing movements of leaves in the trees, watching a cat on a clear mission slink under a hedge, and probably thinking about Halloween and how much I’d like to be able to fly, as these were strong preoccupations for me. Suddenly, however, I became aware that the two girls across the aisle were talking about me.

“I don’t know. I’ve never seen her before,” said one, in an amused whisper.

“Yeah,” said the other, giggling. “Me neither. She must be in Special Ed.”

I came back to myself. Special Ed? And then the gut punch… SPECIAL ED?! I was in ESP!!! Humiliations galore! I pulled back to observe myself: odd clothing was a given, but there I was also, sitting hunched over my arms, which hugged my body laxly, palms up and fingers curled aimlessly in my lap; forehead against the glass; and, horror of horrors, mouth hanging wide open for no other reason than that I was completely relaxed and not used to thinking about how I might look to others. I closed my mouth cautiously, so as not to alert the girls that I had heard them, and then I eased myself “casually” into a more upright and dignified position. She must be in Special Ed.

My dad was magic. I could see that much for myself. My aunts and uncles and grandparents were storied. I had just begun to think that I, too, might be able to control my own destiny - I just won myself a place in ESP! But in 4th and 5th grade, a rift began to open up, between how I saw myself, and how I realized, for the first time, I was being perceived by others - namely, not brilliant; not precious or extraordinary; and definitely not magic. Just a fat Alaskan Indian. In funny clothes. And probably in Special Ed.

These were challenging years, as I first became aware of myself outside the safe and protected womb of my home life, where I greeted the idea, with some astonishment, that I even had an identity separate from my family. I was the Chan Clan. The Chan Clan was me.

Not so, I learned. An accident of genetics. I am chubby and strange and slightly ridiculous. It’s only natural that only my family would really love me. What right do I have to take up space or attention out there in the world?

The final nail in the coffin for me, though, just as I was beginning to founder in this way, was likely…

The First and Last Time I Heard Dad Say Fuck

I was ten years old and suddenly speechless. It was high summer and the greenery sped past the window behind his head in a dense, lush blur that contrasted with the steeliness of his face in profile. “That fucking son of a bitch,” he said through his teeth, “I’m going to crucify him by his nuts.”

My eyes widened and I stared down at my legs, pulling my hands closer into my lap. Fuck AND nuts in the same sentence!! For a moment I forgot to breathe. I glanced sideways at him from the passenger seat and could see his hands on the steering wheel in a vice-like grip, his teeth bared, clenched around the stem of his pipe, and lips moving as he continued to spit and hiss incoherently. Dad didn’t swear – oh, the occasional “goddammit” and “S.O.B.” might fly around here or there – but nothing like this. This level of rage would have scared me in and of itself, but today it made my blood run cold because it meant that I had been in real danger, maybe even worse than I imagined. And, too, there was the inescapable implication of his words.

“Y-…you know who it was?” I asked, scanning images through my mind of all of our neighbors up and down the street. All the UNICEF collections, all the trick or treating, all the hellos, smiles and waves….

“Yeah, I know.”

“How do you know?”

“I just do,” the thought of which seemed to unleash a new wave of fury. “That goddamn pervert,” he said, starting to half-laugh, maniacally. “I’m going to string him up BY HIS DICK.”

Dick??? I looked at my feet dangling below me and noticed that they were dirty, and still bare. There had been no time for shoes. The man on the other end of the line had asked if I would talk to him while he masturbated. And then suggested he come over so we could “play doctor.” The only reason I even knew the word masturbation was because I had read the YA classic novel Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret. With my stomach at my feet, I fumbled for the words.

“Um, my dad is here,” I stuttered – lamely. Desperately.

“Oh, I don’t think so,” the voice said, amused and breathy. Excited. “I just saw him leave a few minutes ago. He won’t be back for a while, I guess. You know how he likes to kill time at the diner. I’ve been watching you for a long time now. You and your mother and sister, too. Karen and MeeRa. Yes, I know you all. Such beautiful girls, I see you at church and around town….” And then, with desperate, almost strangled conviction, “I’m coming over right now.”

I dropped the phone as a shower of ice and fire shot up and down my spine, my scalp prickling hotly, while drops of sweat popped up at the hair line around the back of my neck. I raced out the back door, scanning the yard and street – up and down. All was quiet. I grabbed my bike, which was a new “big kid” 10-speed. Built as it was for more serious cyclists than the typical 10-and-under crowd, though, it had sharp pedal spikes to prevent slippage. Now those spikes stabbed painfully into the bottoms of my bare feet, as I pumped my legs. I stood up to get more leverage, tried to stay upright while checking frenziedly over my shoulder to see if I was being followed, and winced as my ankles lost stability, jerking forward and backward without warning. My toes scraped the pavement each time, picking up bloody lacerations. I knew where Dad was and so ignored the pain in my feet for four blocks, a whooshing sound thundering in my ears, until I reached his favorite hangout - the Calico Kitchen, the local diner on our sleepy little Small-Town Main Street.

He’d be eating chicken noodle soup and a Belgian waffle, I told myself, or donuts and coffee. He would certainly be mid-laugh when I found him because that was his way. I held that image in front of me like a talisman. When I reached the corner where the diner was, I jumped off the bike before it had even come to a stop, sending it into a cacophonous clatter to the pavement. I stumbled through the door, sobbing and emitting strangled screams, searching wildly for Dad and causing, I imagine, considerable consternation among the other customers. But I had no eyes for them for there he was, just as I knew he would be, having lunch and laughing with the waitress; I felt all my fears fall away from me and collapsed onto him in a heap.

I don’t really remember what happened after that. The next thing I knew, we were speeding down a winding and secluded road and I was getting a lesson on the verbal proximity of fear to rage. Because I didn’t know it at the time, but Dad was scared. Maybe as scared as he had ever been. An undefeated boxer in his youth, 33-0; a Colonel in the US Army, who had taught guerilla warfare training; a man who had survived capture, sniper’s bullets, malaria, typhus, mortal hand-to-hand combat; who had hijacked a plane to fly himself back over enemy lines to freedom; and who had relieved three men of a knife in Harlem one night, which he still kept sitting on his desk as a reminder of what he was capable of. But he couldn’t protect his own daughter from the man across the street. And It shook him.

He took me to Letchworth State Park that afternoon – the “Grand Canyon of the East.” Magnificently scenic, it was a good 35 miles south of Rochester, and a bit of a drive. I don’t recall that we did much talking either. Just driving in silence, and sometimes getting out and looking. There were gorges and canyons, waterfalls and roaring streams. Water, wind, and birdsong competed for center stage. I knew that Dad liked to go there and take pictures. He had one of Mom from their dating days on his desk; she looked elegant with a bun low on her neck, staring wistfully out over the canyon, legs crossed, and perched on a stone wall. Letchworth meant good things to him - new love, second chances, limitless future.

I think he didn’t know what else to do, other than to take us to a beautiful place, his beautiful place. A place that reminded him somehow of what it is we’re all doing here anyway.

Some words can’t be healed with more words.

Sometimes silence and togetherness are not only enough, they are all that remain. I thought that myself, years later, when I sat by his bedside, holding his hand before he died. I remembered the drive to Letchworth Park that day and took comfort in the feeling that I was doing all that was needed.

We never spoke about what happened again. I never found out who it was that called me that day, although I have an idea. I know one thing, though; although no one on my street ever turned up strung up by the dick, I never got another phone call. And I know monsters don’t stop monstering unless somebody makes them. And I know you don’t want Bob Chan making you do anything.

Dad saved me. The world is a big and scary place, I learned. You’ll never make it on your own. Find the saviors and champions, never let them go. It’s taken me 37 years to start unraveling that knot. Writing - and telling stories - is a big part of that.

Reparenting

Things happen, you know? A series of events. In a particular sequence, and maybe in a number of different places. Various actors are often involved. One thing happens, and then another. I’ve pulled them together here into three little stories, because this particular group of random and otherwise unrelated events feels like it holds the key to a lot of what I am afraid of to this day, and maybe some of what is holding me back in my writing project.

So, I experienced some things, and maybe I took the wrong lessons from them. I didn’t know they were the wrong lessons, of course. I was just a little kid. To me, they came across as what writer, Lisa Cron, has called “hard-won pieces of savvy intel.” I gathered them up and hoarded them away as a roadmap to survival and success.

More interestingly, if I look at the most challenging relationships and circumstances I’ve encountered in my life since then through the lens of those improper “lessons” I had “learned” during those fraught couple of years, then they start to look a whole lot different. What used to be “disappointments and betrayals I suffered, and deserved, at the hands of others” became an indication of “unhealed wounds of my own, which had set me up for feelings of disappointment and betrayal.” And as for what I deserve… it is everything good and to shine on. Same as you. What a difference this slight change in perspective makes.

Now what to do with this new-found knowledge? If these little stories hold the key to why I am stuck in my book - I doubt myself, I am afraid I’ll be rejected if I shine too bright, I fear success as somehow “undeserved,” “accidental,” or “selfish” and think the most interesting thing about me is my perfectly inspirational family (that can therefore have no flaws). How can I integrate these misbeliefs, heal from them, and let them go?

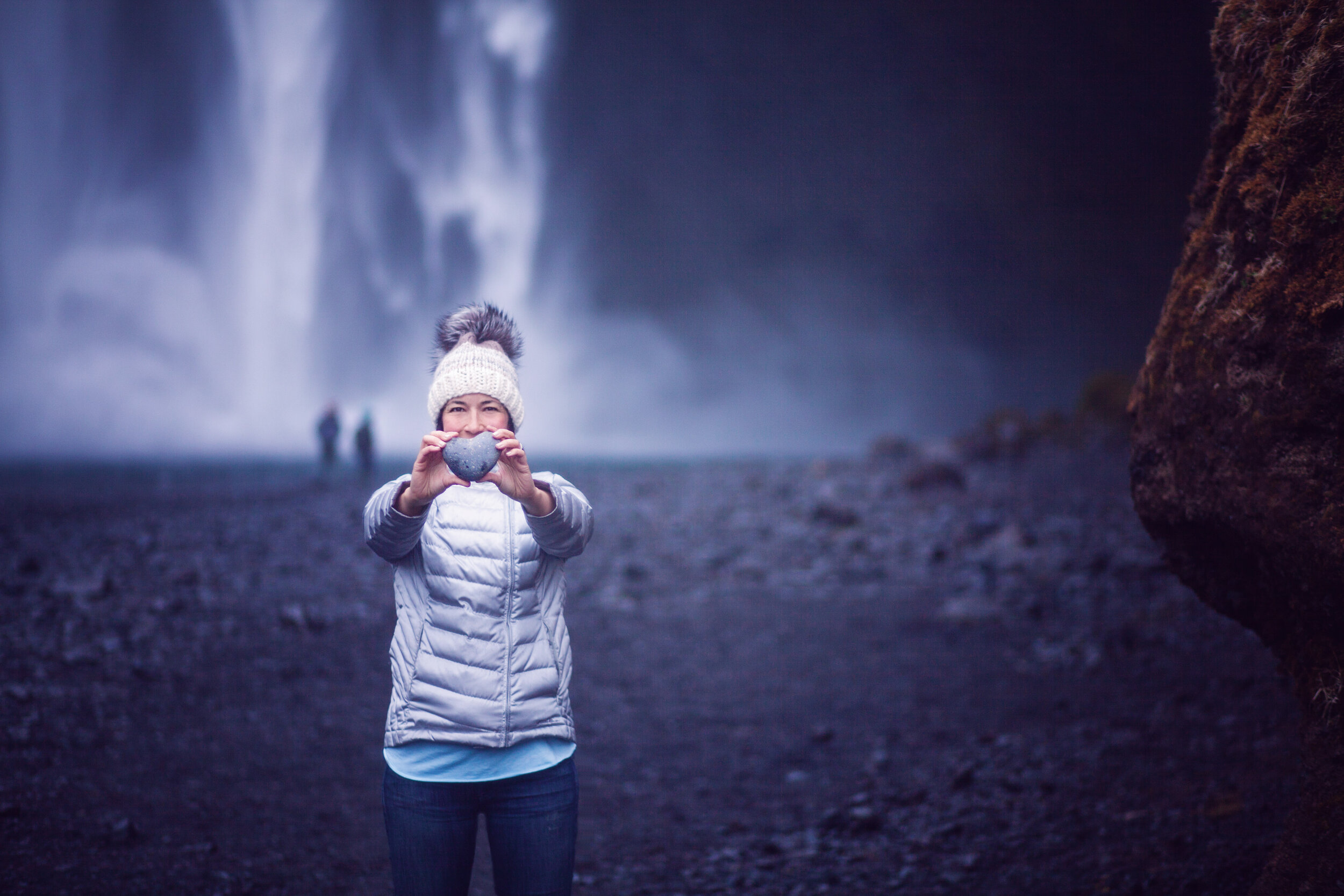

I went to bed last night with these questions on my mind, knowing that I needed to figure them out if I was going to be able to finish this blog post, let alone finish a book. And as I drifted back and forth over the threshold of sleep, I became aware that I was standing at the base of the mighty Skogafoss, my favorite waterfall in Iceland. I was close enough to feel the billowing vapor and cold spray on my cheeks. The thundering waters created a low vibration in my chest. I had one hand stuffed tightly into the pocket of my silver coat. The other was holding the hand of a child. I looked down and saw…myself, about age 9. Hmm, that’s curious! Her hair was in two messy braids and she wasn’t wearing a coat. She stood tense and trembling by my side, pressing her knees together and clenching her other arm to her chest, where she bounced lightly up and down, teeth chattering. She looked up at me and I could see excitement, eagerness, and uncertainty playing all at once over her face - is it okay for me to be here? And it struck me just how intolerable it was to imagine a child such as this one ever needing to ask that question. In truth, I had never seen a brighter, more earnest, imaginative, kind, and yes, beautiful, child in all my life, and I was overcome with emotion. I knew immediately what I needed to do. I fell to one knee, wrapped her in my arms, and held her tight, as if I could save her, and as if only she could really save me.

“My darling,” I said to her. “You are precious to me beyond measure, and I will love you forever.” And I meant it as much as I’ve ever meant anything in my life.

I felt her trembling cease as she relaxed into my embrace. The moment felt so incredibly good because I was feeling it from both sides, the giving and the receiving of love. I was infused and saturated with it. And then I fell asleep.

And here is what I think has happened. I was called to dredge up these old stories to tell them first and foremost to myself (thank you for listening!). In doing so, I have uncovered a part of me who, despite wonderful parents and a solid upbringing, did not get all of her needs met. For decades, there has been a wounded and fearful child hiding in the wings of my subconscious, yearning to be seen and more importantly, cherished, and acting out in ways that I was not even aware of because she did not feel either of those things. And now that I’ve rediscovered her and shone a light on her, I don’t have parents anymore who can hug that hurt away. But I can hug the hurt away. It reminded me of the quote from The Faerie Queen:

“For whatsoever from one place doth fall,

Is with the tide unto another brought:

For there is nothing lost, that may be found, if sought.”

It means that whatever you have lost, no matter how precious, can be found in other forms elsewhere. It won’t be the same, but if you stay curious, and are willing to look, you will find that it is enough.

So here, then, is another reason why we tell stories. Stories, if told right, can show us where the wounds are. And stories, if told right, can help us stanch the bleed. On the other hand, it turns out that I’ve been telling myself other kinds of stories that have been threatening to hide and perpetuate the old wounds that no longer serve me.

My vision showed that my destroyed sense of home, belonging, and feeling safe in how valuable I am - could be found again inside myself, and not just as airy metaphor. I can quite literally be a parent to myself, or at least the wounded part of me who still needs one. All I have to do is close my eyes and conjure it, and I don’t feel lost or alone anymore. And doesn’t that mean that I’ve effectively found my way back to the Shire?

Stories brought me home. Just like I thought they might. Now I save myself. Just like I hoped I would. At long last, I am neither orphaned nor homeless, and that’s the best story ending I’ve ever told.

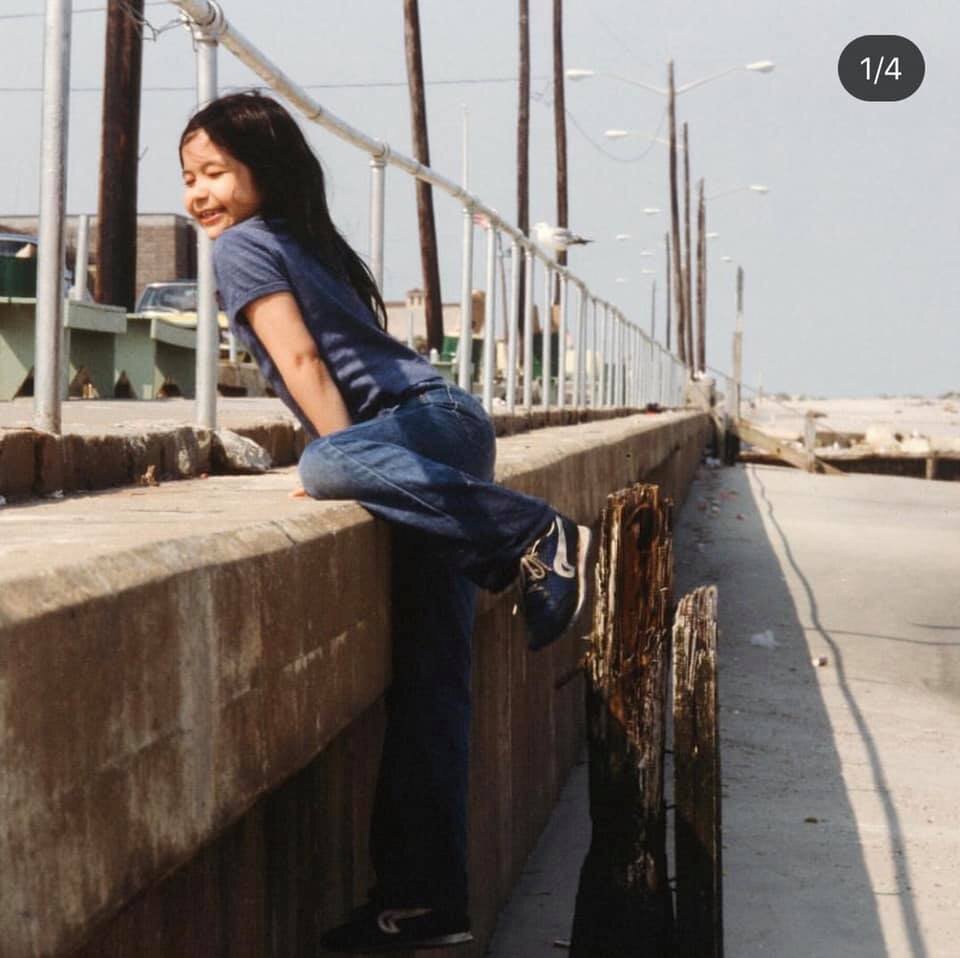

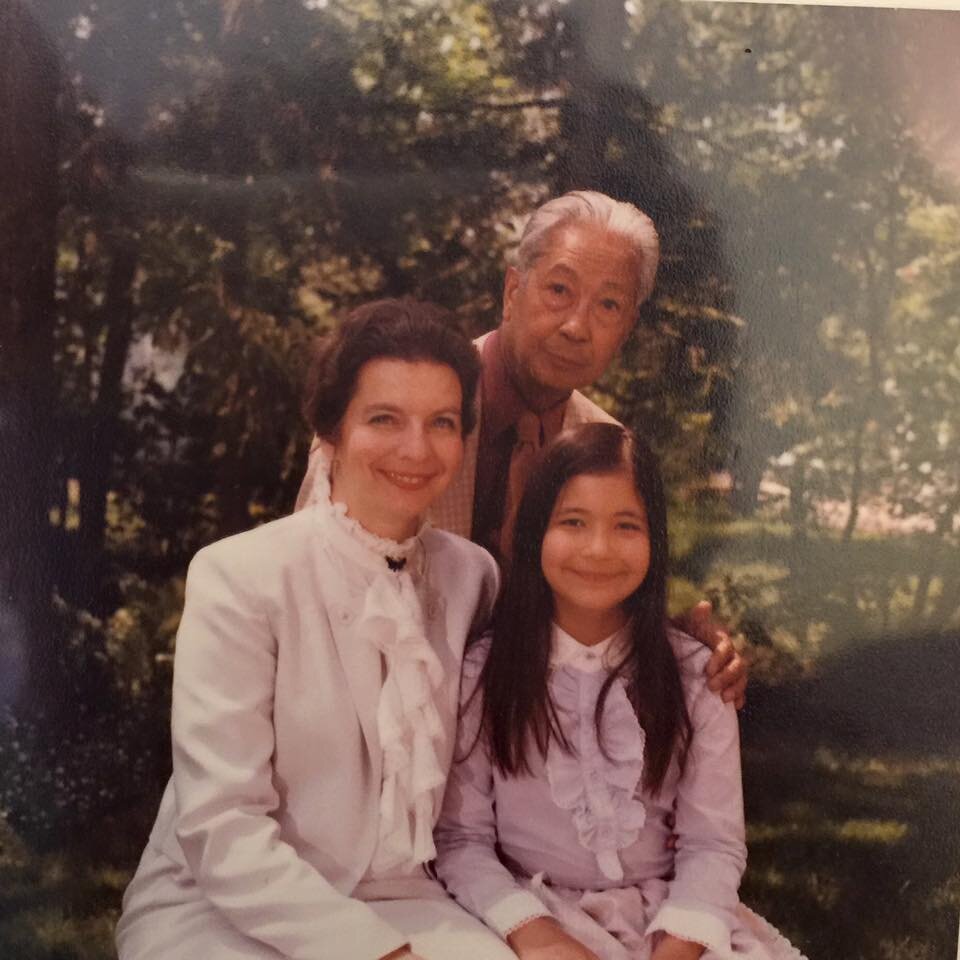

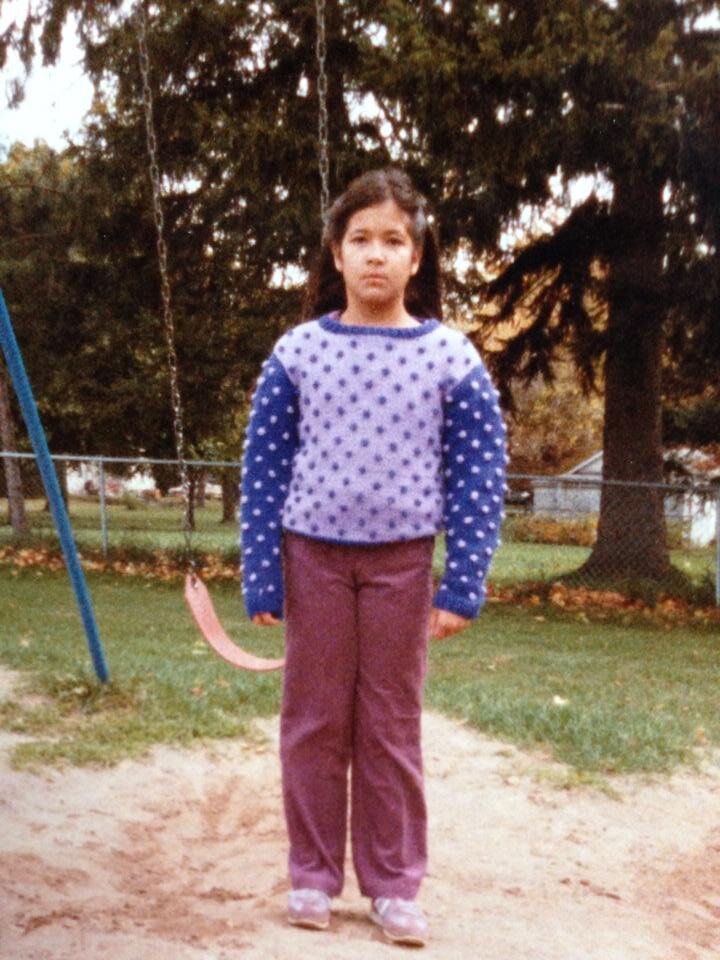

UPDATE: Today, just one day after publishing this post, “Facebook Memories” coughed up the pictures of me below - pictures that Dad took of me, on another occasion…at Letchworth State Park, when I was about ten. It reminds me of what he told me in Ghostwriter: “You don’t really think you’ve been doing all this writing by yourself, do you?”

Like, Comment, and Share!

Although the buttons below work, Squarespace is currently struggling with a bug that erases the tracking at random. I’ve lost hundreds of likes and shares from throughout the blog, and new ones also tend to disappear (NOOOOOOOO!) So please don’t let low or no numbers shown deter you. Likes and shares still help boost my visibility and readership, even if the numbers don’t stick around to show it. Thank you for reading, liking and sharing!