Small Wonders

“Dear Family (What a lovely word, and how blest are they who have one!)”

"Magic happens. Magic happens. MAG-IC! HAP-PENS!" The phrase reverberated in my mind, repeated, punchy and insistent; staccato and relentless, like rain on a tin roof, as if to carry it through the powerful amnesia that can obliterate even the bare moments between waking and opening one's eyes. I have seen the most elaborate, vivid and wonderful of dreams vanish without so much as a "pffffffffft," simply because I had the poor sense to open my eyes.

I reached clumsily to my nightstand and created a sonic clatter of ceramic, plastic and shuffling paper, sending my glasses to the floor, before remembering that what I was looking for was already on the floor. I grabbed my writer's journal and pen and fumbled to push the light switch and find the next clean sheet of paper. What date was it? My half-sleeping mind couldn't compute and so I left it. "It's not important anyway. Just write it down," said the voice in my head. So I wrote at the top, "5 ____ 2018, Magic happens." And then I began to scribble as fast as I could everything that I associated with that. Full sentences, partial phrases, single words that I hoped would be enough to jog my memory later.

Here is the list:

Jungle ambush

Astral projection

GG's lamp

Slugs

Double rainbows

Order of the Good Death

Team Chan

This is our relationship now

Through a glass, darkly

The gap

No try, only do

GG's poetic license with Chan misery

the Sound and the Fury

The writing is barely legible because I knew my grasp on these ideas was tenuous and time-sensitive. If I allowed myself to snap back to full wakefulness, or stop to find "just the right words," they would be gone. Magic happens, magic happens, magic happens. But this is often the way that it happens, and if you aren't ready for it, it will pass you by for a more ready recipient.

The truth is, if I did not believe in magic, this blog and book I am working on might never have been started.

Old Chan Magic

But I'm a scientist, you might point out; why do I believe in magic?

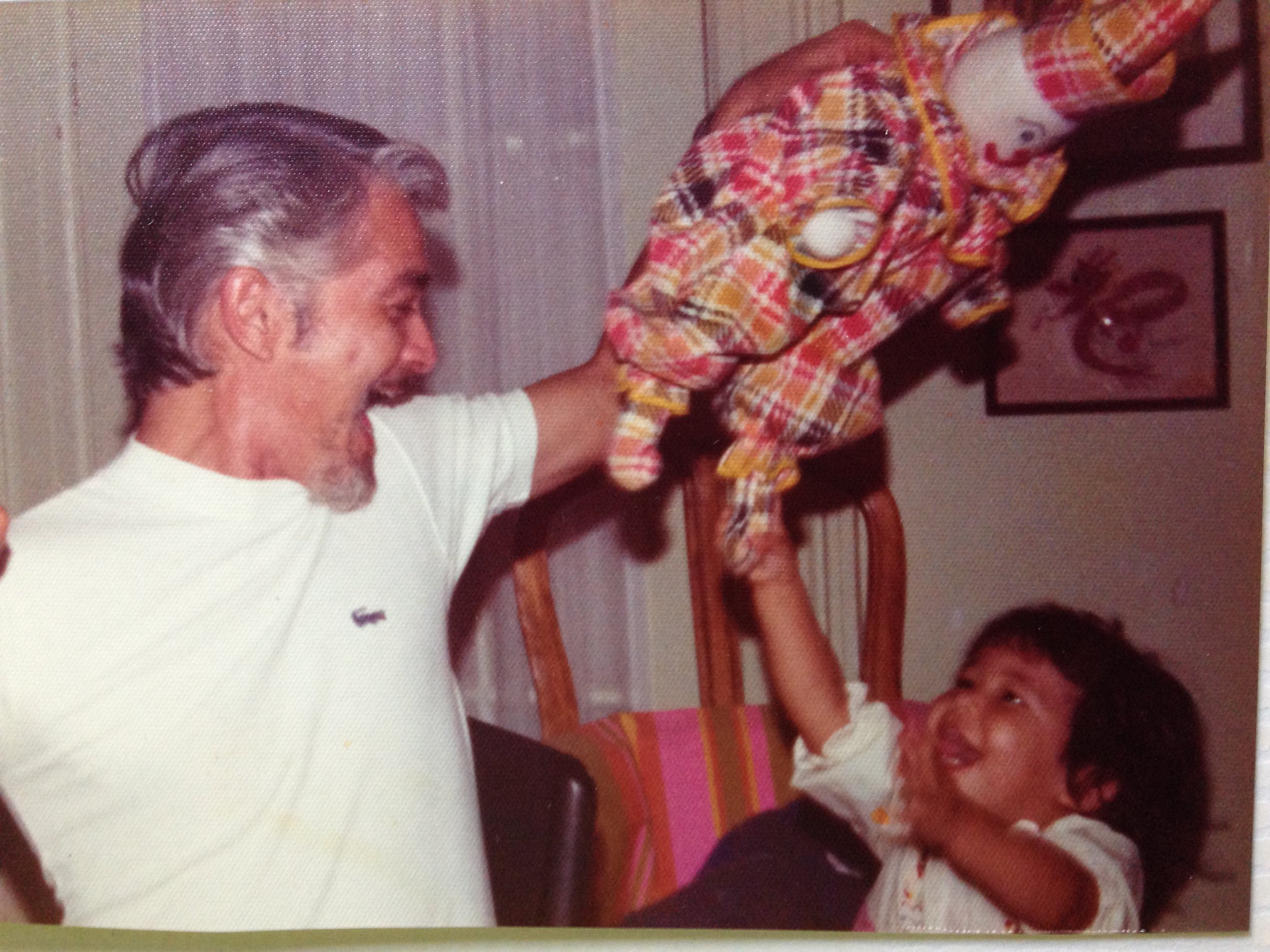

Maybe it started the day that Dad grabbed the nose from my face, which sent my hand flying up to check and make sure it was still there. Luckily it was... but then, how could be it there in his hand? I wondered about it for weeks. Maybe it was the way he could wrap his pointer and middle finger around his thumb and then lift at the joint and take the top part of his thumb with it. "Did it hurt?" I asked. And he let me feel the joint - smooth and flat; hmmm, no blood or shards of bone, I noticed. Curious, verrrry curious. I looked up and checked his face for clues. There was none. Only a twinkle. Maybe it was the summer morning that Dad brought me outside before breakfast - barefoot and in my nightie - and leaned down in a hushed whisper to point out the fairy circle of toadstools that had sprung up overnight after a wet period.

"Where are the fairies?" I asked, breathless, squatting to peer under the nearest bush to make sure I hadn't missed anything. I felt the damp hem of my nightgown stick to the back of my calves when I stood up, and saw wet segments of fresh-cut grass stuck to my toes.

"They only dance in the moonlight and when they know no one is watching," said Dad. Catching the disappointment in my face, he pressed on, "But sometimes they get drunk on dew and fall asleep and you can catch them out in morning, if you're a skilled observer. Looks like maybe we just missed them." My mind reeled and I played with the toadstool ring for the rest of the day, until it shriveled and disappeared.

When Dad died, a woman at his memorial stood up and said that "Bob always seemed a little bit...magic to me." The pause was pregnant, as if she thought people might find that an odd descriptor. But rows upon rows of heads nodded in agreement. Another likened him to Peter Pan. Of course, I knew just what they were talking about. What they didn't know was that Old Chan Magic ran wide and deep. Dad had just been their, admittedly, very charismatic and addictive, "gateway drug" to the real Source.

(note: if you are on mobile, turn phone horizontal to read captions for slides below)

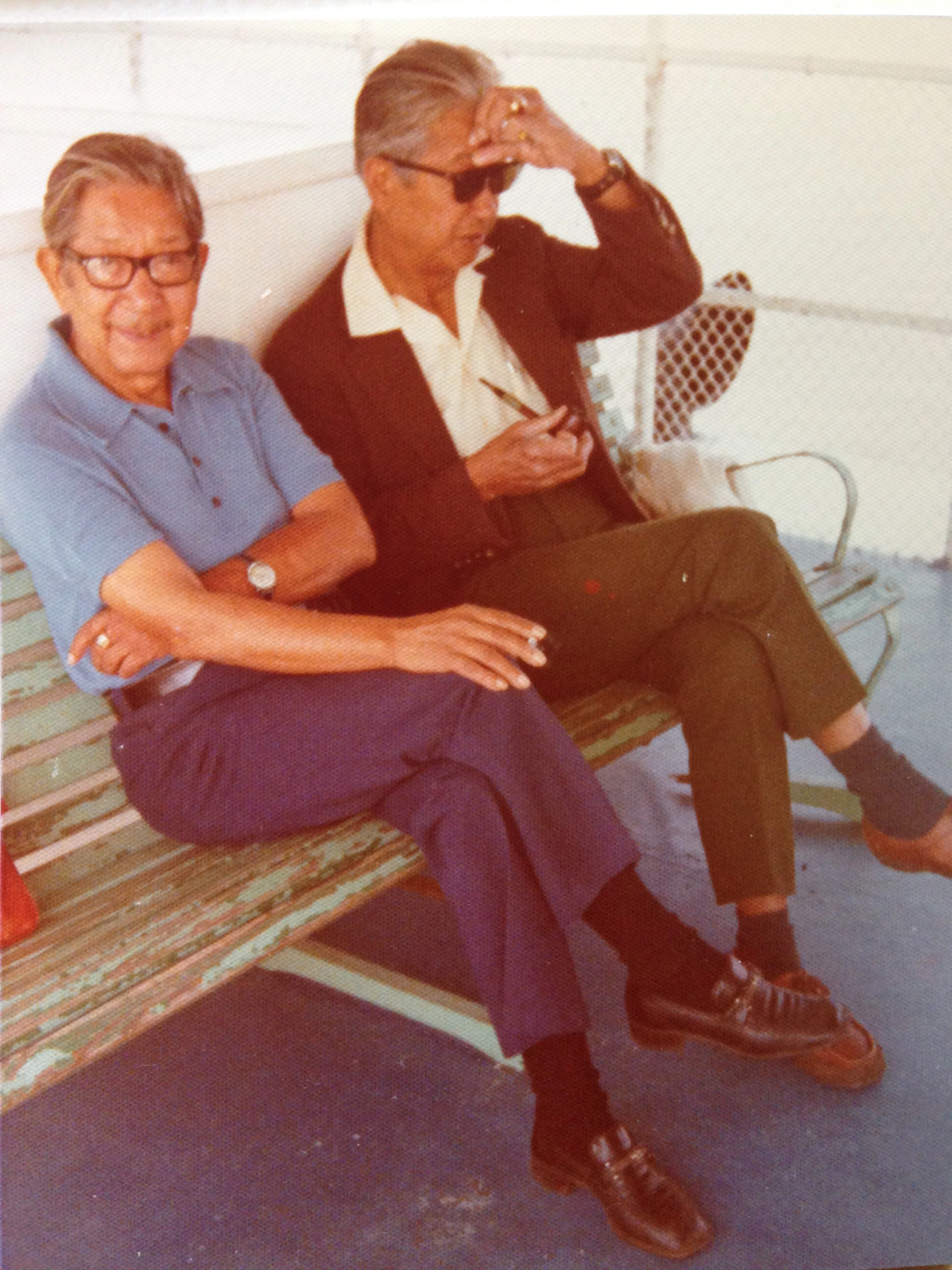

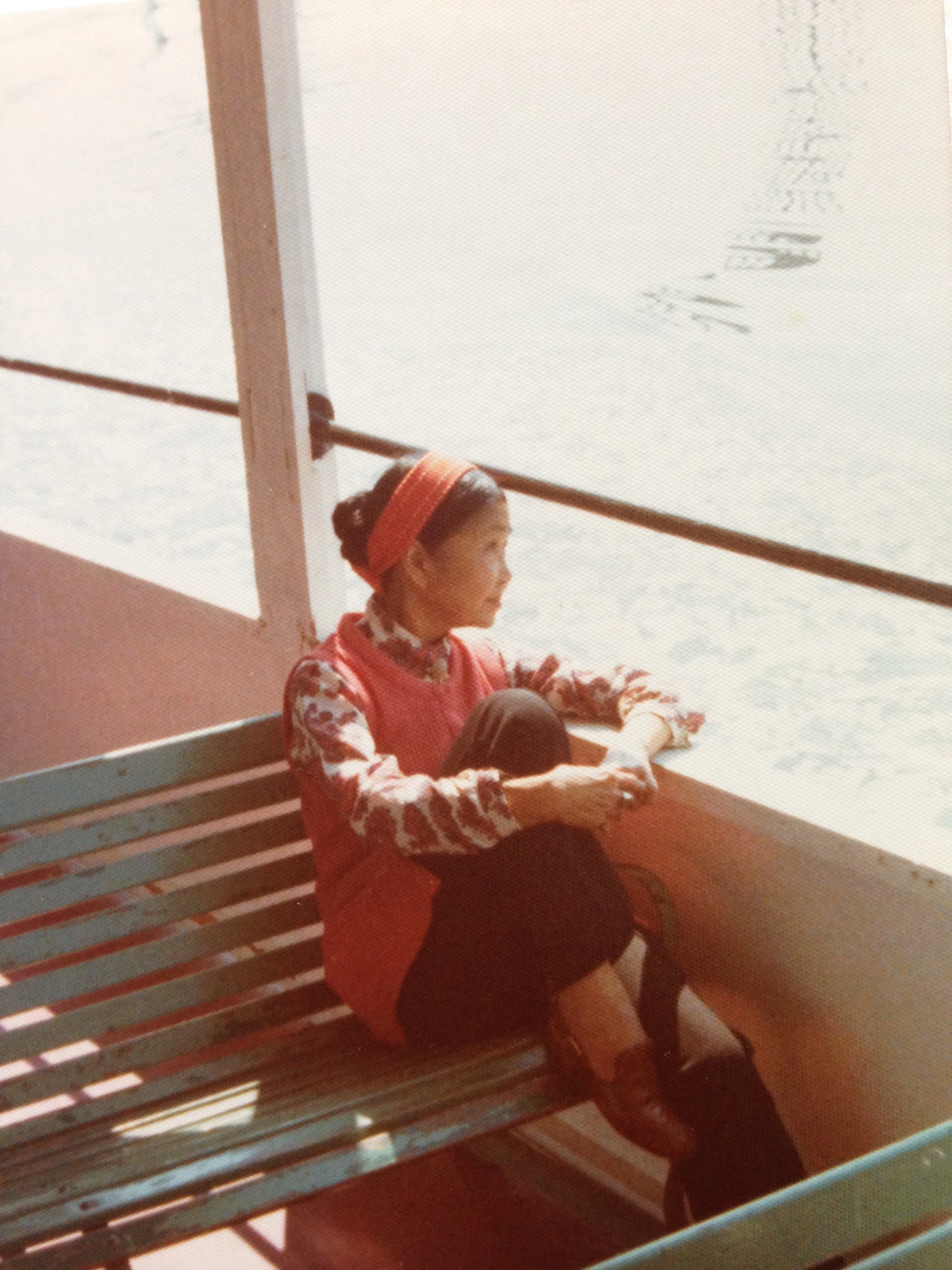

Every summer the family hopped in the car and made the 2-3 day drive down to Savannah, Georgia to visit with the Chan family - the Source - all the uncles and aunts and cousins. Grandma and Grandpa were long gone, but there was still a huge family down there in the 1970s and 1980s. Savannah, to me, was steeped in magic that had only little to do with the twisted limbs of the live oaks and the hanging moss. True, the effect was that of a veil, which covered everything and begged to be lifted. At night, steamy cobblestone streets released a fog that swirled around antique light posts in the squares turning them into soft glowing orbs. It felt to me, as if there had been cast a glamor on this place. Things were not always what they seemed, for better or for worse. But that wasn't just a bit of moss and fog talking; that was Old Chan Magic.

* * * *

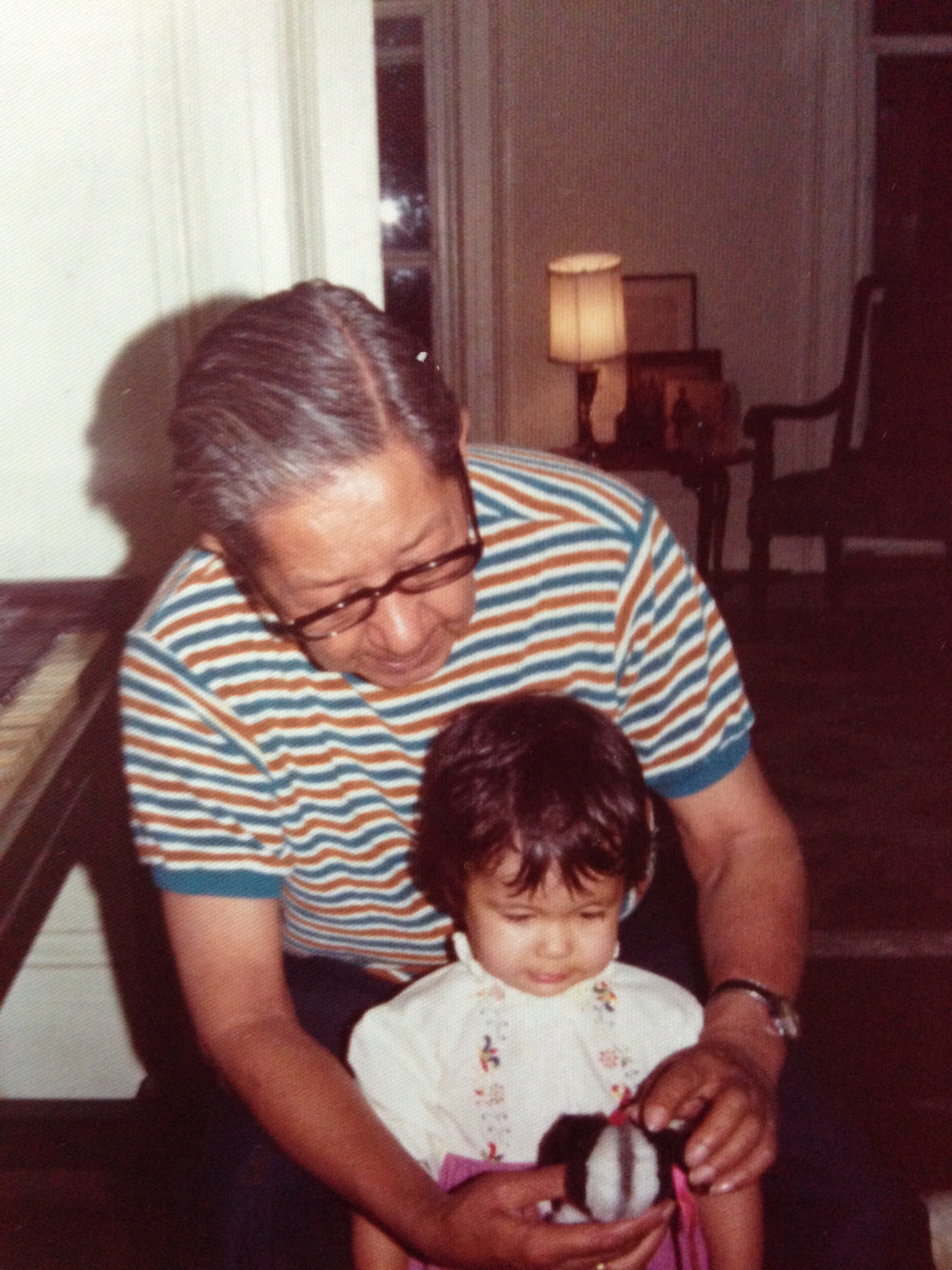

"Do you hear them talking?" asked Uncle Sandor, as he turned around in the front seat of the car, making the vinyl creak. We were sitting in a parking lot waiting for someone to come out of the Piggly Wiggly after one of those big southern rain storms. He wore his signature short-sleeved striped polo shirt, not quite buttoned to the collar, and in a shade of blue that accentuated his skin - brown, beautiful, and impossibly smooth for his age. His eyes gleamed at me, expectantly, the same way Dad's did when he swiped my nose. I was the Chan family's own small wonder. No one expected me to come along at this stage in the game, when most of my aunts and uncles were settling in to retirement, and my cousins were parents and even grandparents in their own right.

Sandor was waiting to see how long it would take for me to discern who "they" were that were "talking," but of course I knew immediately.

The windshield wipers, squeaking on the glass, had clearly been saying "Sleepy Sally, Sleepy Sally, Sleepy Sally" since the moment we pulled away from the curb at his house on Sickel Drive. Uncle Sandor said they had something different to say every day if you were willing to listen.

Yesterday, they had been going on about potato salad.

Another time, I sat sullenly on an orange and green flowered sofa in GG's eat-in kitchen area. I had slid all the way down so that only my head was propped against the back cushion, and my feet, in little brown t-strap Mary-Jane shoes, dangled an inch or so above the wood floor. I stared straight ahead with my eyebrows knit into a frown. Mom was nowhere to be seen, and Dad had probably thrown up his hands and stalked from the room long before, muttering about my being "a pill." He had no patience for pouting children, perhaps because he knew no remedy if you were unwilling, and Dad, you must understand, liked to fix things.

"Do you think Alexka will talk to her Aunt Gerald?" asked GG of no one in particular.

I shook my head vehemently and clenched my jaw tighter. She tried bringing me out about her cats, Frodo and Miranda. Miranda was the smallest and Frodo easily the biggest cat I had ever seen, and since Miranda was Frodo's mother, they made a comical pair, and no one had a greater passion for cats than I at the age of five. So GG was not wrong to try the cats first. But I was immovable.

"Well, you're doing it wrong," interjected the lamp on the side table next to me, seeming to address itself to GG. My eyes jerked to the left where the lamp was, and then quickly over to GG, who was sitting there quite still and with a knowing twinkle in her eye. I looked straight ahead again, determined not to be tricked out of a mood. "Oh really?" GG asked the lamp. "Yes," said the lamp imperiously, "any fool can see she's had it with people." And then, more solicitously to me, "Haven't you, girl?" The voice was gravelly and small and sounded like a goblin or an elf on his third horn of mead, but not frightening in the least. I slid my eyes more slowly this time back to the lamp and considered. And then, because the lamp had got it just about right... I nodded.

"But you would talk to me, wouldn't you?" said the lamp. "Because I'm not a dirty rotten human being, I'm just a lamp." I sat a little higher on the couch and nodded again. I looked to GG who kept smiling at me, still twinkling, legs crossed, not moving a finger. "What seems to be the trouble, little girl?" said the lamp.

And I turned straight to the lamp and leaned in on the armrest and said to it, conspiratorially, so that GG might not hear, "Daddy's a liar. He said we were going to go to the beach and catch clams today, and now we're just going grocery shopping."

"I hate when that happens," said the lamp, with gratifying emphasis on the word "hate." "Why are you going grocery shopping?"

"A family party," I said, rolling my eyes and flinging myself back into an aggrieved slump.

"I hate family parties," said the lamp. "They're the pits." I giggled involuntarily because I actually did love family parties, more than anyone had a notion of. "What do they need groceries for?" the Lamp pressed on, "Let's just feed them cat food." I laughed out loud, forgetting all about the fact that I didn't like to show my teeth when I smiled. And that was that. Add perfect ventriloquism to the list of small wonders one was like to find if you hung around the Chans for very long.

It wasn't that everything was a bowl of cherries, mind you. Dad had stopped visiting family sometime around 1950 for reasons that are even now unclear to me. All I know is that things picked up again when Mom (and I) came in to his life.

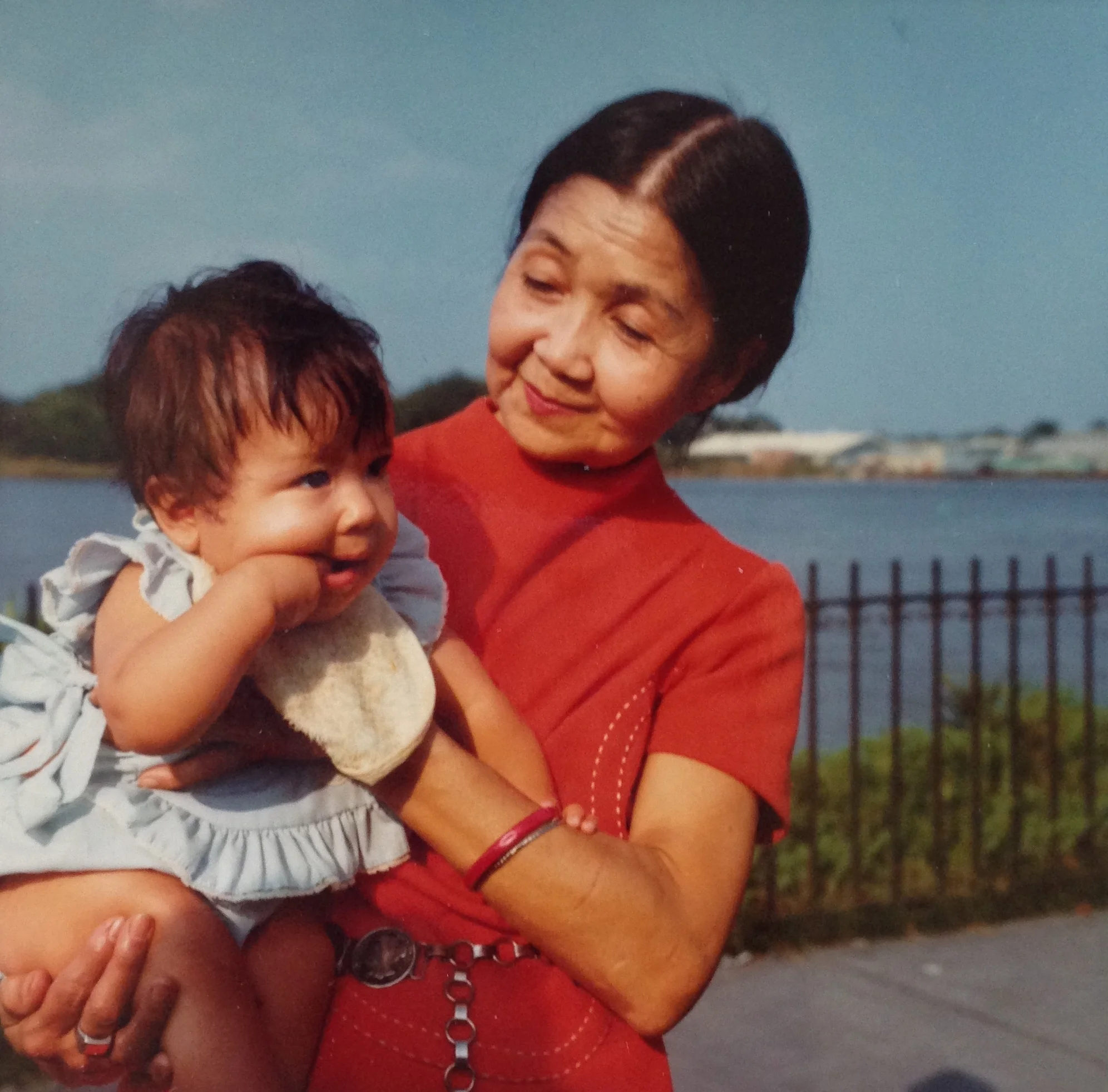

But GG was a poet, and the Keeper of Dreams in our family. She knew your heart and sussed out your greatest yearnings without your even having to speak them. What is more, she caught them for you and kept them safe, filing them meticulously into the family lore as if it were already a done deal, even if you yourself fell spectacularly short of what you had intended. All you had to do was want to be something, and you were it already in her eyes. Everybody was their best self in her calculation: a writer, a film-maker, a showman, an artist, a hero. Isn't that the most magical thing of all? Dad called it poetic license, which was his own euphemism for denial. But I knew it was more complicated than that.

It was GG who showed me that the best way to find magic was to actually look for it, and she set about doing it at slightest provocation. Even the giant slugs that came to the stoop and invaded the cat bowls on humid mornings – the width of my hand and two flights of stairs up! How ever did they get there?

She presented these otherworldly beings to me as closer to fairies than goblins. To her they were tiny nighttime revelers, “wingless, footless, boneless, blind,” riding on mysterious moonbeams to her door. One day she wrote a poem about them, “Snail without a Shell,” and she called them fondly a “lethe for old pain.”

I tell you, to call a slug beautiful and then make another see it, too, is Old Chan Magic in action. GG taught hushed reverence before ugly things but, because she frequently cussed, wore one earring - like a pirate - so she could always answer the phone comfortably if called, and had a crush on Magnum P.I., she breathed witty irreverence. Nothing is to be taken too seriously, she seemed to say, nor was it meant to be. Least of all, ourselves.

To believe in magic, you have to have this combination: an expectation that beauty and mystery can be found anywhere; a willingness to search for and see it; and a deep and unabashedly held belief that oneself is not to be taken too seriously.

“Willingness is next to Godliness”

In October of 1995, GG wrote Dad a letter, excerpted below, shortly after our latest visit:

[...] Now back to our quarter century of annual visits. Our members (all the generations) lacked none of the faults that other families display: pettiness, gossip, criticism, coldness, misunderstandings, downright lies. But somehow this group has had that streak of nobility that kept us together - since there have [also] been mutual admiration, sympathy, generosity, union in sorrows, happiness in attainments, pride in achievements. I like to think that our father and mother could come in and join us smiling, because they had brought up "good" children. As I go over the second, third, and fourth generations, I thank the mates we have had to produce such excellence.

The Sinnie problem has meant a silent telephone. However, I wrote her to explain how you had to get going on a day's notice, just as you told me to do. Her birthday is celebrated from the actual day 11/6 to 11/11, formerly Armistice Day. If possible, I hope you will send her a note or card. "Be ye kind one to another."

Robert Earl, you have stayed young, strong, with legs good-looking enough to go bare down Bull Street! I am sorry you don't ever want to meet any of our old friends so that they could see how you look and talk. I thank your wife for some of that! (The physical, not the indifference to the "friends.")

Love to all

And then three weeks later:

Sinnie called the Sunday night after you had gone. She was most amiable. She felt that you had come down because of Eunice's death to see the family and especially Nannelle. So she did not regret missing your visit, as she said she hated death and burial events and never went near them. Said you, Robert Earl, had "matured into a good person" and that the two of you could talk for hours, both so well educated and traveled.

I didn't meekly say, "Well I ain't never been to no collitch or been much farther than Pooler 'cept wunst or twicet."

Your visit was a pleasure to all of us. But nothing erases the years when this place had cots and suitcases all over, and midnight lemon pie (homemade) and trips to the night spots with SANDOR AND AT LEAST ONE PLAY. These caps [all-caps letters] are volunteers, not of my making.

We have much to be thankful for, all of us. Muchas gracias, Padre Dios. Pardon errors. The light is terrible in "before dark of morning."

Karen, I was so happy to see you walking [after hip replacement], calm, and your nice, diplomatic self. You need it among the mad Chan Clan.

Gerald

I grew up steeped and rooted in this sort of everyday magic. Lamps could talk. Fairies were real. Slugs were old friends. A stuck caps-lock key only made your letters more lively and fun. Disappointments and failures were just steps along the way. And serious family rifts were distilled down to a hilarious essence that, if it didn't always heal, at least did a lot less harm. I suppose all this left me ... willing; open to see things from a variety of angles; able to seek and find beauty in ease as well as in hardship; and ultimately, aware that some things just need to be felt rather than "explained" or "understood."

The question is, are you now willing to take your dose of Old Chan Magic with me? If you aren't then you're going to miss half the show later on. So gather 'round, friends, because I am going to share with you three family ghost stories. And if you are lucky, that Old Chan Magic is going to cast a glamor upon your day, and temporarily inoculate you against the bitterness and cynicism of the world. And who knows what can happen when bitterness and cynicism are overcome, even for a day?

Exhibit A: Ba Comes to Visit

When Dad was eight or nine - old enough, anyway, to remember - Papa (my grandfather) came to the breakfast table with tears streaming down his face. His father was dead, he said.

"WHAT?!" cried the family in a great eruption. Mama dropped the iron frying pan full of sausage, making a great clatter on the stove top. Archie, the oldest, stopped mid-chew, his biscuit hanging limply from his fingers. He felt a stabbing tightness in the pit of his stomach. Any significant changes in family fortune fell heavy on his shoulders. Sandor was goofing off as usual, until Sinnie slapped him. Gerald had one hand over her mouth and Bernice, the littlest, looked around confusedly.

The Chan kids had never met their grandparents - on either side - but there was the Chinese Christmas box that came every year and brought with it bright papers, exotic items, teas, foodstuffs, and aromas from what Papa called "home." They knew the phonograph records of Chinese opera that Papa would put on after the laundry had closed. They watched from the stairs, looking through the balustrades, as their father - always working, always working - turned the dial at day's end to full volume and eased back into his chair, eyes closed.

The kids plugged their ears at the clanging cymbals that bashed their ear drums and the screeching falsetto voices that rose and fell in great cacophonous waves. They laughed at the cat clawing its way up the stairs in a panic; and shook their heads at their father whose face exuded only radiance. They knew that the pictures they had taken out in the courtyard or at the photography studio around the corner, all dressed in their Chinese costumes, were mostly for A-mah and A-yeh.

"What do you mean?" said Mama and all the children, questions tumbling over each other. “How can you know? When did the mail come?" Papa said he didn't need any mail. He had awoken the night before and seen his father sitting at the end of the bed, weeping.

His face frozen in disbelief and alarm, Papa had scrambled upright in the bedclothes. He screwed his eyes shut and opened them again, widening them to make sure he wasn't dreaming. "Ba?" he had said, clutching a fold in the sheet. But there was no answer. His father only hung his head in his palm and wept.

Papa had fled China over 30 years before, at the age of 19, escaping his own beheading by the Empress Cixi for his leadership in the rebellion that would eventually depose the dynasty. He never saw his home or his family again. That is a tale for another time. What is important here is that six weeks after Papa came to breakfast with heavy heart, a telegram arrived from China - Ba was dead, and he had died the night that Papa had seen him weeping at the end of his bed.

Exhibit B: Jungle Ambush

America entered World War II when the rest of the world had been on fire for over two years. The fighting took place on multiple fronts, and required the proverbial "all hands on deck." America's "Europe First" strategy made it imperative, therefore, that China stay in the war in the East to tie down more than a million Japanese soldiers who might otherwise interfere with the Allied defense of the Pacific. The problem was that China was depleted from years of fighting and might never have been up to the task of mounting an effective defense against Japanese military might to be begin with.

In September 1940 the Japanese invaded French Indochina and cut off all sea and rail access routes for supplies to the Chinese mainland, and in April 1941 they signed the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact, which further cut off land routes through Russia or Turkestan. Only the Burma Road remained, then, as a link to China from the outside world. And with the fall of the Burmese city of Rangoon (now Yangon) and the airfield at Myitkyina (pronounced MITCH-en-aw), even this last life line was cut.

So by early 1942, when American forces were really getting underway after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, China - a key ally in the Pacific - was hobbled. It was the Allies' mission to use India as a staging point to eject the Japanese from Burma and build the Ledo Road to restore land communications to China - from India, through Burma.

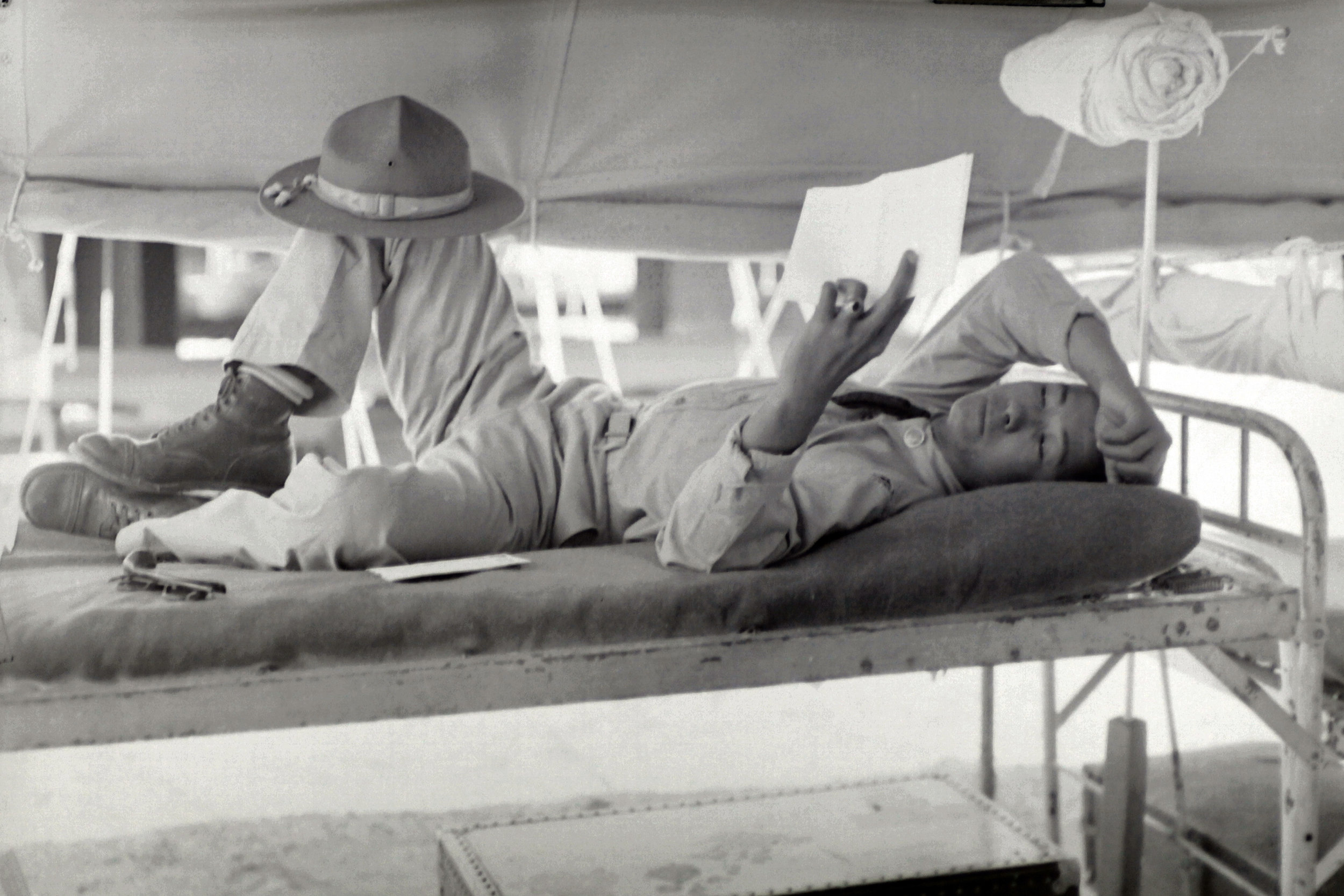

To that end, and in the summer of 1942, General Joseph "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell established The Ramgarh Training Center on a tea plantation in India. He further thought that Chinese soldiers could be as good as any, if properly trained, as survivors straggled over the Indian border, starving, wounded, and in defeat. He recruited Allied officers from around the world to come to Ramgarh to train these soldiers in the weaponry and jungle warfare (i.e., guerilla) tactics developed in the West, and raise vast polyglot armies to fight the Japanese. Dad was among those officers called, and he arrived at Ramgarh probably in October of 1942, which is when the Americans took over operations from the British there. He was put in charge of Chinese troops and he taught hand-to-hand combat, weaponry, and other guerilla tactics.

Meanwhile American engineers arrived in December and started construction on the road. The problem was that Burma, besides being roughly the size of Texas, is also one of the most inhospitable places in the world, with jungle so thick that whole armies could pass in short distance of each other without knowing it.

To march through Burma was to hack through wilderness in a perpetual, often deadly, struggle against Nature. Climate extremes of intense cold, smothering heat, and three months of monsoon rainfall greater than anywhere in the world, combined with dense jungles and swamps, where cholera, malaria, brush typhus, berry-berry, dysentery, and tropical fevers and sores claimed the lives and limbs of many Allied soldiers - and the morale of most all.

Furthermore, there were the mountain barriers of the Himalayas and no roads. Supplies were brought in on mules. Imagine trying to supply an army with what a single-file line of pack animals can carry over treacherous mountain passes. Many mules fell to their deaths in mud-slides, or by losing their footing on the narrow paths, taking the supplies and sometimes their Sherpa with them.

Meanwhile air supplies had to be flown in "over the Hump" - the highest part of the highest range in the world - some 15,000 feet up through a cauldron of air currents that caused ghastly and near-constant levels of turbulence. Great gusts hurtled planes toward earth, like giants spiking a ball. Planes flipped upside down, were lifted uncontrollably to dangerous heights only to then be dropped into free fall. Hail, sleet and torrential rain were the norm, and roiling thunderstorms appeared out of nowhere, blacking out all visibility and turning the heavens into a bubbling mass of treachery where no man could tell up from down, earth from sky. Yes, finding a land route was critical.

Conditions on the ground for building a road, however, were hardly better than conditions in the air for flying a plane. The Ledo Road project dealt with impossible terrain, monsoon rains that repeatedly washed away progress, and equipment and supply shortages. How exactly does one get a steam roller over the Himalayas? Asking for a friend....

Meanwhile the jungle was so dense that there was almost zero visibility and the lurking dangers were legion - anything from an ambush squad of Japanese soldiers to pythons, insects, bears, leopards, or angry baboons that can rip a man limb from limb. Yes, did you know? American soldiers were sometimes killed by local wildlife.

Dad screened the advance of the road, sent with his guerilla teams as "long-range penetration groups" behind Japanese lines to gather intelligence, blow up bridges and rail lines, call in air strikes, rescue downed allied fliers, and engage in guerilla warfare tactics when necessary. I asked him once over a sandwich why they needed hand-to-hand combat, when they had guns. Why didn't you just use your guns? "Did they jam in all the wetness of the jungle or something?"

"No," he said, hesitating. It brought him no pleasure to intrude on my innocence. "No. It was because we had to kill silently."

At the time of this story, Dad had Captain's rank and was moving his men through the jungle from Point A to Point B. He had received word from intelligence, however, of a Japanese ambush planned for somewhere en route between those two points. The problem was that they couldn't tell him where it would be.

Scouts sent ahead a few days prior had not yet returned, and timing was everything so Dad and his men embarked anyway. They followed a faint trail through the jungle. The jungle is awash with sound - birds, crickets, monkeys, snakes, insects. Modern eco-tourists and travel bloggers in Myanmar are likely to describe jungle treks as invigorating - a must-see experience that is well worth any fleeting discomforts. But for soldiers it was more akin to being buried alive. The foliage closed in around one, hiding untold terrors from view and inviting your imagination to do its worst.

The constant chirp and whir of crickets seemed to emphasize the asphyxiating heat, and the lonely call of an Asian Koel sounded like a slide-whistle piercing through the din. As the call increased in pitch and frequency, like string instruments in a thriller, so too did the men's sense of suspense and dread on the ground.

And then there was the silence, in between all the sounds, barely discernible but felt in the marrow of one's bones - falling heavily, menacingly, and like a choking blanket. It was the silence of death.

Eventually, Dad came to a fork in the trail and stopped, not knowing what to do. Down one path lay certain death; down the other, only possible safety. It was a Hobson's choice and he stood there, paralyzed with the weight of it. Sweat stung his eyes. No one spoke. No one moved. The Asian Koel sang its song.

Suddenly, he caught movement ahead. Narrowing his eyes and honing in on the source, he saw that it was one of the scouts, a friend of his, who had gone on three or four days before. He suppressed the urge to let out a "whoop!" of celebration. Far ahead on one of the paths, at the bend, the scout looked back from behind some dense foliage, jerked his head and beckoned silently with his hand, "this way." And then he disappeared. Dad followed.

Each time they came to another bend, he looked ahead and there was his friend, beckoning them on. This continued for several hours, and Dad anticipated some hearty handshakes and a slap on the back at day's end. There would be stories to tell.

As the day waned, the men reached the end of the trail - safe. Alive. But what they found was the scout's body. The level of decomposition indicated that he had been dead for several days.

Dad would never say one way or another what saved them that day. He knew what he saw. But he also talked about dehydration, paranoia, fever, terror - the dark magic of the jungle. I suppose it could be partially attributed to those things. But I'm pretty sure I know what he saw. Aren't you?

Exhibit C: Dream House

It was during these long-range penetration missions that Dad began to have a recurring dream. It was of a well-appointed house, somewhere in America. This house evoked many lovely emotions in him: safety, home, a sense of belonging.

The dream was always the same. He walked down the path leading to the front door, entered the house, and wandered from room to room, enjoying the sense of ease and feeling of the familiar. He did not know what the meaning of the dream could be, nor was the house anything from his life back home, so he chalked it up to jungle and battle fatigue. Who wouldn't want a lovely home to retire to in their dreams, while their body rotted in the jungle mud and wet, shivering with malaria and nearly expiring from brush typhus?

“It’s funny how we’ve learned to laugh at our misfortunes. Take dysentery, for instance.”

Dad's letters home were alternately humorous and grim about field conditions. In Delhi the men called it "Delhi Belly," he said. At Ramgarh, they were the "Ramgarh Runs." And here on the Ledo Road, they were the "Ledo Leaks."

Dearest Sweetheart -

If I stay here much longer I'll go crazy. We die if we don't eat, and if we do eat we get the [redacted by Army censors] -sentery). We get dhobi itch from the washing and B.O. if the clothes are not washed. We studied language in one dialect and the men speak another. The only two congruous things over here are that I love you and you love me. (4/28/1943)

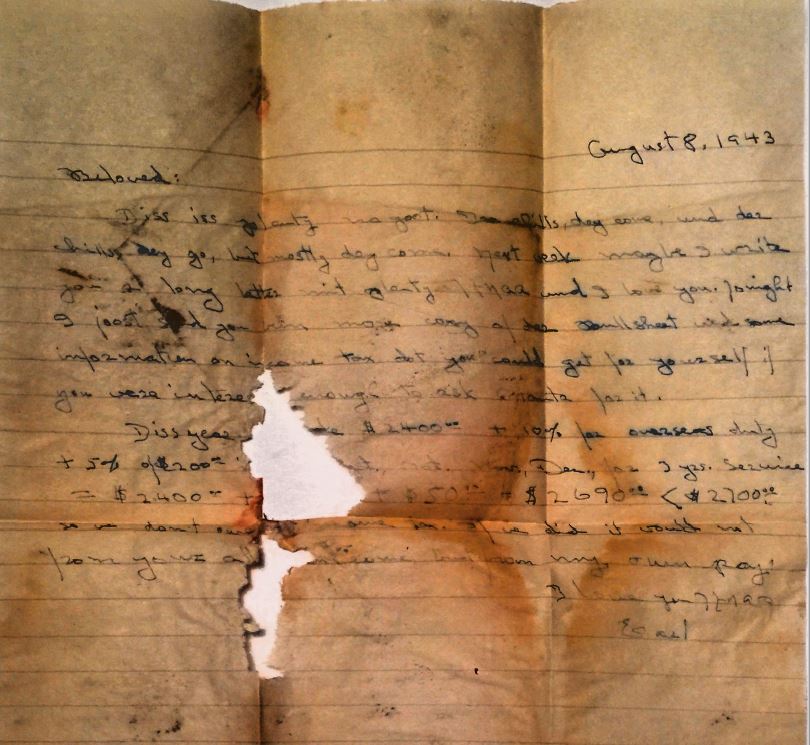

Or take this one, the paper browned and rotting by rain, sweat, and mold, perhaps even blood - a rambling missive from the depths of a fever dream. It begins,

Beloved:

Diss iss plenty no goot. Da chills, dey come and da chills, dey go, but mostly dey come.

Brush typhus, a mite-borne form of the illness, made him wish for death. It didn't kill him, but it left him nearly sterile. Nearly.

The dream house was a welcome respite.

At war's end, he returned home and was stationed for awhile in Washington D.C. One day he was out for a drive in the outskirts of the city when he started getting a powerful sense of déjà vu. Everything was strangely familiar though he had never traveled this route before. And as he was trying to sort out this uncanny feeling, he drove up on the house from his jungle dreams. He stopped the car, incredulous, and stared. His ears started ringing and his vision swam for a moment.

And then he made a snap decision. He got out of the car and strode to the front door. He took the brass knocker in his hand, hesitated, and then let it fall. Footsteps approached on the other side and a black woman opened the door, dressed in a domestic's uniform. She appeared to be in the middle of cooking. She took one look at the man standing before her, and her eyes turned round in an unmistakable expression of fear. She let out a yelp and slammed the door. Footsteps hurried back into the depths of the house. Dad stood on the porch for a moment and decided to knock again. He simply couldn't turn away.

This time the "lady of the house" appeared. She saw Dad in his uniform, stared for a moment, apologized, and invited him inside. She asked the cook to bring lemonade and finger sandwiches. The woman, still visibly shaken, curtsied and fled to the kitchen. The lady invited Dad to sit in the parlor, and they did their introductions and made a little small talk. Dad was exceedingly good at charming banter, so I am sure this part was lovely.

But while they talked, he scanned the space around him and realized that he knew where every room in the house was. He asked if he could use the bathroom to wash his hands and found that he knew where that was too. He went there in something of a daze, rinsed his hands and splashed water on his face. Patting himself dry, he stared at himself in the mirror above the basin. When he returned, the woman asked "Lt. Col. Chan, it has been so lovely to spend this time together, but what is it precisely we can do for you?"

Going over the possibilities in his mind, he decided to stick to the truth. He said, "Mrs. Pratt, thank you so much for your hospitality in this exceedingly unusual intrusion upon your day. I must tell you that I felt compelled to come to the door because while I was in the jungle in Burma, I had a recurring dream about this house. And I had no idea what it meant; I only knew that I felt good here. And when I saw the house as I was driving by today, I recognized it instantly. Then I came inside and I knew where to find everything - even the bathroom.” He lowered his eyes in discomfort. “I only asked you where it was to be polite."

Expecting to be laughed at, invited to leave, or at worst - threatened with police action - he awaited her response with trepidation. But who could have foreseen what happened next?

"Well," she said, "that doesn't really surprise me. You see..... we've seen you here many times."

* * * *

In his final months, I talked to Dad and reminded him of this story. I told it to him just as I did here and when I was done he teared up and nodded, momentarily at a loss for words. Yes, he remembered. "I don't know what it was," he mused, choking back his emotion, "that told me I belonged there."

I told him that I tell our boys this story and it is one of their favorite stories of all time and this pulled him from his reverie, bringing back a hearty laugh. "Oh?" He said. "And what do they say about that?"

I said "they think your life has been full of magic."

He was silent at this, his eyes fixed someplace in the distance. And with another glistening in the eye, he said "Yes" and nodded, turning his eyes back to me. "That it has."

To life's small wonders, then. The ones that delight us, the ones that heal, the ones that save and the ones that, well, instill a sense of wonder. Magic happens. Indeed it does.

Like, Comment, Share!

Although the buttons below work, Squarespace is currently struggling with a bug that erases the tracking at random. Please don’t let low or no numbers shown deter you. Likes and shares still help boost my visibility, even if the numbers don’t stick around to show it. Thank you!