Orpheus

I love you, darling, and I could go on writing all night. But I’ve got to write home, and the radio has so much to say [about the bombing of Pearl Harbor two days prior] that I’ve got to see what is being said. - Earl

P.S. Bob bought himself a 50c pipe. He’s heard the girls saying how peaceful and relaxed I look smoking mine, and how much they like to smell the smoke, and how much they like a man “who smokes a pipe,” so he rushed out to make arrangements to “look peaceful and relaxed” and to let them “smell the smoke from HIS pipe” and to have them fall over HIM. […] Right now he looks like a self-conscious frog with a stick stuck in his mouth, and he keeps asking “don’t you think I’m remarkable? I’ve started smoking a pipe! Don’t you like to smell the smoke?” HA! HA! HA! HA!

- Letter from Dad to soon-to-be-wife Gretchen

December 9, 1941

Dearest Darling,

Two significant things happened to me today, the first (the most wonderful thing that’s happened since I got your Christmas message) was that I got the eight letters you wrote before Christmas. I must have worn the writing off. I’ve read them so many times for this was the first word I’ve received from you. […]

The second thing is that I broke my most cherished possessions – Orpheus and Morpheus. Ever since I arrived in India I’ve contended that the native drivers are more of a menace to life than all the axis soldiers combined, and today it was quite forcibly proved. Although I emerged from the incident with only minor abrasions on the elbow and knee (right side) tomorrow I’ll be sore as a boil on that side, and everything in my pockets on that side was broken. I was riding my motorcycle along when I saw a British lorry (truck) coming in the opposite direction. When we were only about 100 feet away from each other the Indian driver suddenly cut across the road to make a turn. He put out his hand, but what good did that do when we were so close? The entire road was blocked, so there was nothing to do but put on the brakes, hold on tight, and wait for the motorcycle to come to a stop from the skid which was inevitable. (The back wheel always comes around and the motorcycle slides down on its side when brakes are applied suddenly). I got up hopping mad and cussing, and if there were not a heavy fine imposed by law for mayhem on a native, I’d have beaten him to within an inch of his life. As usual, nothing can be done, and I’m mailing the remains of Orpheus and Morpheus to you. Please send them to the Kaywoodie people (Kaufman Bros. and Bondy) in New York City to be repaired. […] Keep them safely for me, and some day you’ll sit in my lap while we enjoy a good smoke of Walnut and Orpheus. [...]

I love you,

TFNAA

Earl (February 11, 1943)

The Fifth Sense

My phone vibrated on the couch cushion beside me, letting me know a message had come in. It was from Michael - my nephew who is four years older than I (long story) and Dad and Gretchen’s grandson. “What was the name of your dad’s favorite tobacco,” he wrote, “Captain Black? I can’t remember the name…”

Getting a message like that in the midst of my day, apropos of nothing, often with little or no follow-up, makes me feel less alone. Like a sonar ping sent out from a submarine, it roves the murky depths, listening for echoes of itself. Someone else is out there thinking of our shared past, in meaningful ways and just because. He wants to know if I am too, or if he is alone at sea.

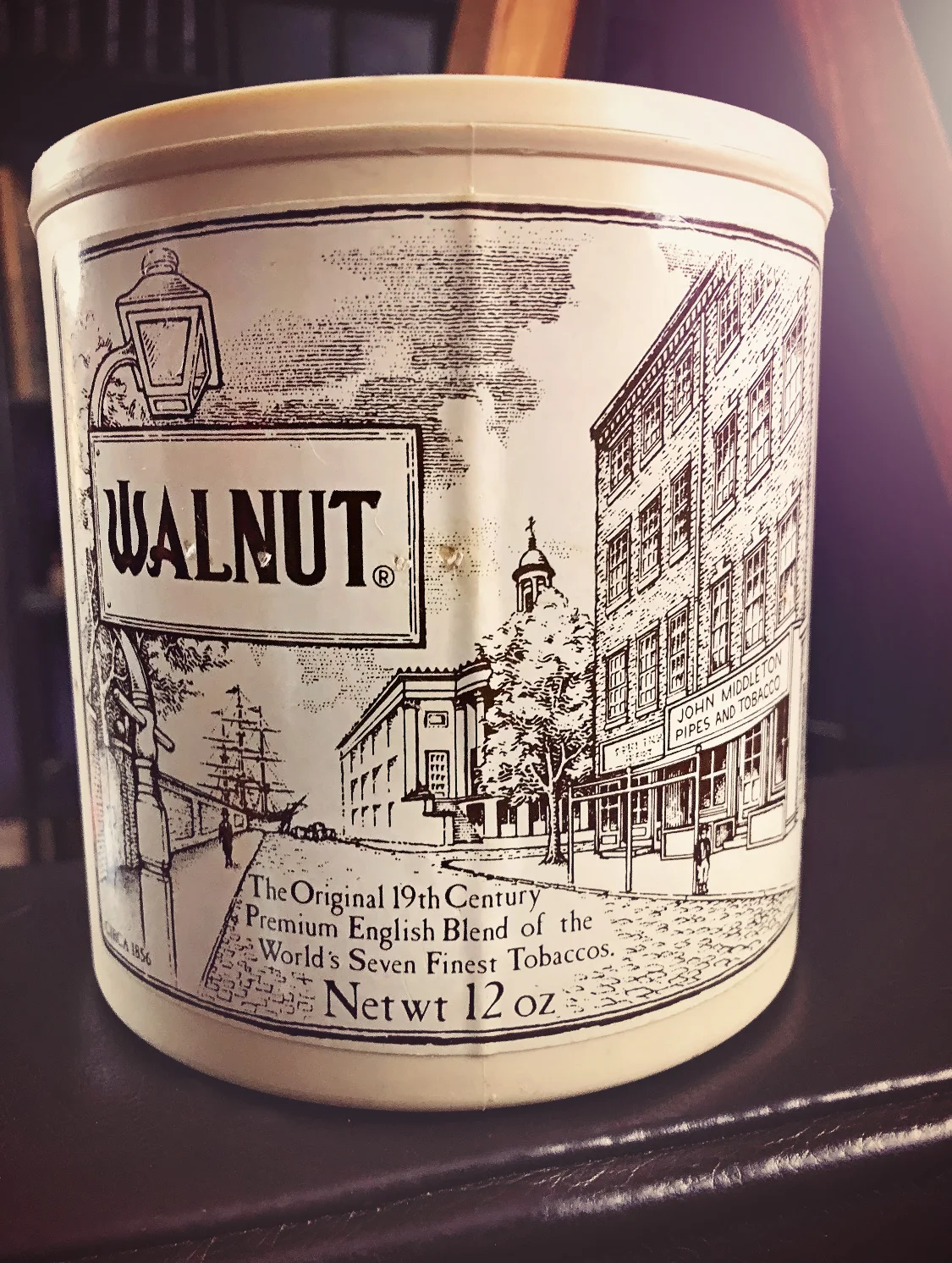

I reflected the pulse back to him: ‘Walnut,” I typed with my thumbs. “Just Walnut.” Then I retrieved an empty canister from the bottom of the hall closet, where it has been sitting full of pennies for the last two and a half years waiting for me make a decision about it: “Use me or don’t. And if you don’t, then why am I here?” I set it on the arm of the couch and took a picture of it to send along with the message.

“The Original 19th Century Premium English Blend of the World’s Seven Finest Tobaccos” says the label, in a wobbly and irregular font that makes me think of the Artful Dodger scuttling waist-high between great coats - an orphaned, wily, good-natured cut-purse, on the loose in London’s foggy streets. I think, in a Dickensian world, Dad would have been the Artful Dodger, rather than the sweet and hapless Oliver Twist. The image behind the lettering shows a pipe and tobacco shop on a gas-lit, cobbled street that leads down to a harbor where merchant ships - sails rolled up on their masts - bob on the horizon, recalling more pungent and exotic shores.

What a drag that all this vintage-y goodness has been slapped onto a beige plastic canister, I thought, not for the first time, realizing that this is why I can’t seem to make up my mind about what to do with the thing. I mean, beige plastic??? Come on.

“Thanks for the picture of the Walnut tobacco,” Michael wrote. “It is so ingrained in my experience with him.”

A simple statement. A simple question: “what was the name of your dad’s favorite tobacco?” But the subtext, I knew, was that Michael misses his Grandpa Earl as much as I miss my dad. For a moment, we were in commune.

“Me too.” I wrote. “I was hoping the canister would retain some of that rich, sweet scent, but it doesn’t.”

“I think the tobacco has to be smoked nearly to when it is placed in the canister to get that succulent, almost opioid presence,” he replied. “I do miss that smell so much. Words cannot describe it.” And then, after another moment, “I’m grateful that I don’t crave tobacco anymore, but holy shit balls, that pipe could put a spell on me.”

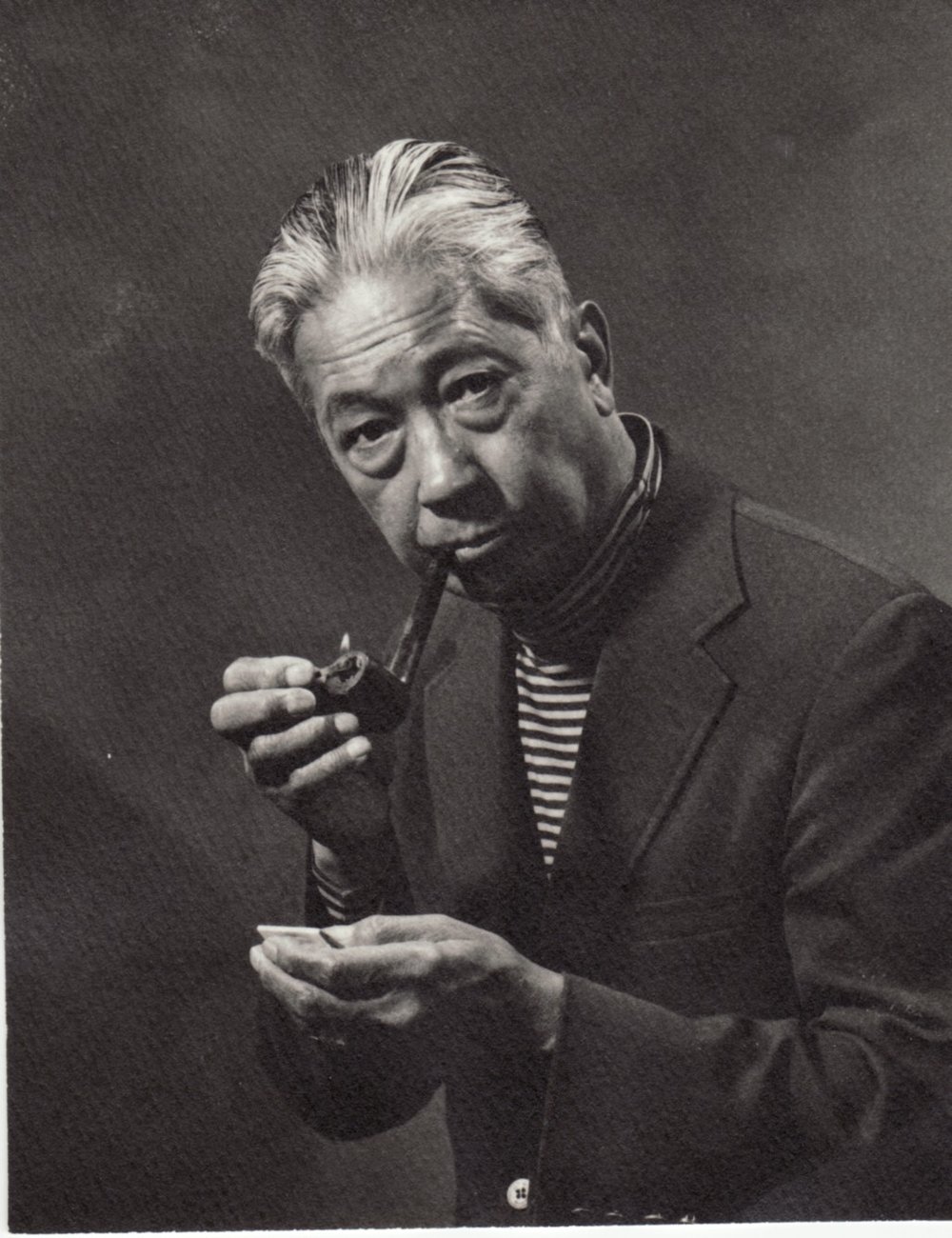

Whether it was the pipe or the man who cast spells on mortal men, I’ll leave for you to ponder. Dad started smoking a pipe when he was 14. I don’t know where he picked it up or why - whether out of curiosity, enjoyment, or youthful rebellion - but he cut a striking figure with one, which he would not have been insensitive to, for he had a streak of vanity that he was wholly unembarrassed about. He used to say, “Well, it ain’t braggin’ if it’s true.” He was rarely to be seen without a pipe in mouth, hand, or pocket again until he was 85.

That was the day the doctor slipped the X-Ray onto the light box hanging on the wall, and turned to Dad, pointing out the small white flecks in the bottom of his lungs.

“Early-stage emphysema,” he said. Seventy years a smoker, Dad quit the pipe cold-turkey that day, (mostly) lost the cough, and lived close to another 20 years un-intubated.

That was long after I had left the house, though, and so the memory of Dad sitting by the fire with legs crossed and a book on his lap, a pipe jutting out from between his teeth, is the very image of … can I say it? Yes, it’s “home.” The smell was warm, mellow and sweet. Cigarettes I find, by contrast, to be abrasive and bitter; cigars, revolting; but Walnut tobacco smoke is smooth. It pours into your nostrils, like a potion, and travels to the back of your throat, hanging there heavy and redolent before the faintest wisps curl forward over your tongue. When it reaches the tip, where the sweet taste buds are, your brain receives the message to be on the look out around here for some kind of candied confection.

“I’m grateful that I don’t crave tobacco anymore, but holy shit balls, that pipe could put a spell on me.”

An unbent paper clip made tinny scraping sounds as he cleared the bowl of the dottle - the unburned tobacco remnants left after a smoke - and then came the fleshy thumping of the empty bowl against his palm as he readied and stored the pipe for next usage.

In conversation, Dad puffed away, making alternatively amused or serious eye contact with whoever was speaking - grunting, chuckling, nodding, blowing smoke, all with a pipe stuck between his teeth. When it was his turn to speak, he brought the pipe down slowly, cupping the bowl in an upturned palm. It was an open pose, indicating receptivity, a relaxed demeanor, and thoughtful, honest engagement with the topic and the person at hand.

If you had touched on a hot-button topic, though, he could grab the pipe from his mouth with remarkable speed and turn the bowl in his fingers in one deft move, so that the stem was now facing outward and could be jabbed threateningly at the vicinity of your chest as an apparent (and Michael thinks, completely intentional) extension of his middle finger.

Literary Familiars

Quick, what’s your favorite animal? Seriously, now. What is it? Think for a moment.

Have you got it?

Now come up with three words to describe the animal and the things that make it your favorite. Write them down.

Go ahead. Do it.

And don’t scroll down and ruin the surprise. Have you got your animal and list of traits?

Now what if I told you that your favorite animal is actually you, or your animal familiar, and the qualities you admire most about it are the dominant facets of your own self - the ones that you most aspire to and most deeply identify with? Feel free to try this on your friends; it’s fun. I asked my husband the question in preparation for this post. Secretly, I have always compared him in my mind to a giant sea otter - lolling around on his back, devoted principally to play and sleep and eating clams, and prone to slipping away in a deep dive if asked to be industrious for any reason.

So when he said his favorite animal was “the sloth,” I suppressed a loud guffaw. Why the sloth? Because it’s “unusual,” he said, “relaxed,” and “reminds him of Costa Rica” (i.e., “vacation”).

“Sooooo…” I said, “you like the sloth because it’s eccentric and lazy?” I snorted in triumph. “Sounds suspiciously familiar!”

“Well what’s your favorite animal?” he asked.

“Jaguar of course. A black one. Solitary; powerful; mysterious and rare; intuitive.” When I told him the trick, we both cracked up. What an odd pair we make. Maybe we should write a book on marriage, The Jaguar and the Sloth, a love story for the ages.

You Are What You Smoke?

It occurred to me that the Favorite Animal Party Trick might be applied to more than just animals. One could try the same exercise with objects that we hold dear, for instance. As an archaeologist, I can tell you unequivocally that artifacts - things - are not just inanimate objects. They speak to you - if you know how to listen, and if you ask the right questions.

Think about the ways that people use objects to make statements about things - who they think they are, how they think the world should be. Artifacts are exciting not just because they can tell you what year or range of years that a soil layer dates to, or how wealthy or poor the inhabitants of a site were. Artifacts are exciting because they offer a window into the mindset of the people who used and discarded them. An archaeologist can take an artifact, or a document, or a landscape, and “read” it for information, not just about a person’s activities or economic status, but also about that person’s dreams, aspirations and daily taken-for-granteds.

Dad bought pipes that are collectors’ items today: Kaywoodies, Savinelli Long Johns, Stanwell Danish Stars, Craigmoors, Peterson’s Kapmeers. As he never had much money, this is a perfect example of how rich with meaning an artifact can be. It goes way beyond a person’s simple “purchasing power.” He preferred the Flame Grains for their riotous swirls of red wood leaping and gleaming on the bowls, their three-dimensional shimmer giving the appearance of flickering firelight. He took pride in smoking Walnut, which he called “the aristocrat of tobacco” in his Kaywoodie, which he called “the aristocrat of pipes.”

He also anthropomorphized his favorite pipes, giving them names and attributing character traits to them that, like the favorite animal exercise above, were only thinly veiled reflections of his own most prominent qualities. There was Orpheus, god of music; Morpheus, shape-shifter and master of dreams; Ulysses (known by the Greeks as Odysseus), legendary wanderer, cunning warrior and culture hero; and Chiquita, the “little girl,” but probably closer to “a hot little number.”

I don’t imagine that Dad consciously named his pipes after aspects of his own self, but upon closer inspection, it cannot be disputed. Dad was a divinely gifted musician. He was a shape-shifter - not in the sense of “hiding” who he really was, but in the sense of honoring and giving full expression to every possible facet of his being - an immigrant’s son who became a scholar; a scholar who became a warrior; a warrior who became an inventor; an inventor who helped spy on an empire. He was a legendary wanderer, a cunning warrior and maybe the most famous culture hero you never heard of (yet!). And he was nothing if not a sassy little spitfire, flirtatious and bold, hard to pin down, and the life of every party.

Orpheus

I learned about Orpheus, Morpheus, Ulysses and Chiquita from Dad’s box of war letters, and I confess having to look up who Orpheus was. As I read about his story, a shower of recognition ran undulating down my spine and out to my extremities.

No mere mortal, Orpheus was the son of one of the Muses and a Thracian prince - a Greek demi-god whose divine gift was that of music. There was no limit to his power when he played and sang; he had no earthly rival. The gods alone were his equal. No maiden could resist the allure of his song, no love he desired could be denied him. Even the stones on the hillside pulled themselves free, and rivers reversed flow and changed course in sweet surrender, wanting only to be nearer to the man with the silvery melodies.

When Orpheus’ new bride, Eurydice, died of snake bite, Orpheus wandered the wild solitudes of earth alone, forsaking the company of men, and finding comfort only in his music. He roamed the world, playing, always playing, until one day, he met a band of people who could not hear his music, and who tore him limb from limb.

“She’s due to fall in love with me this winter, because she said, ‘It’ll be a cold day when I fall in love with Earl.’”

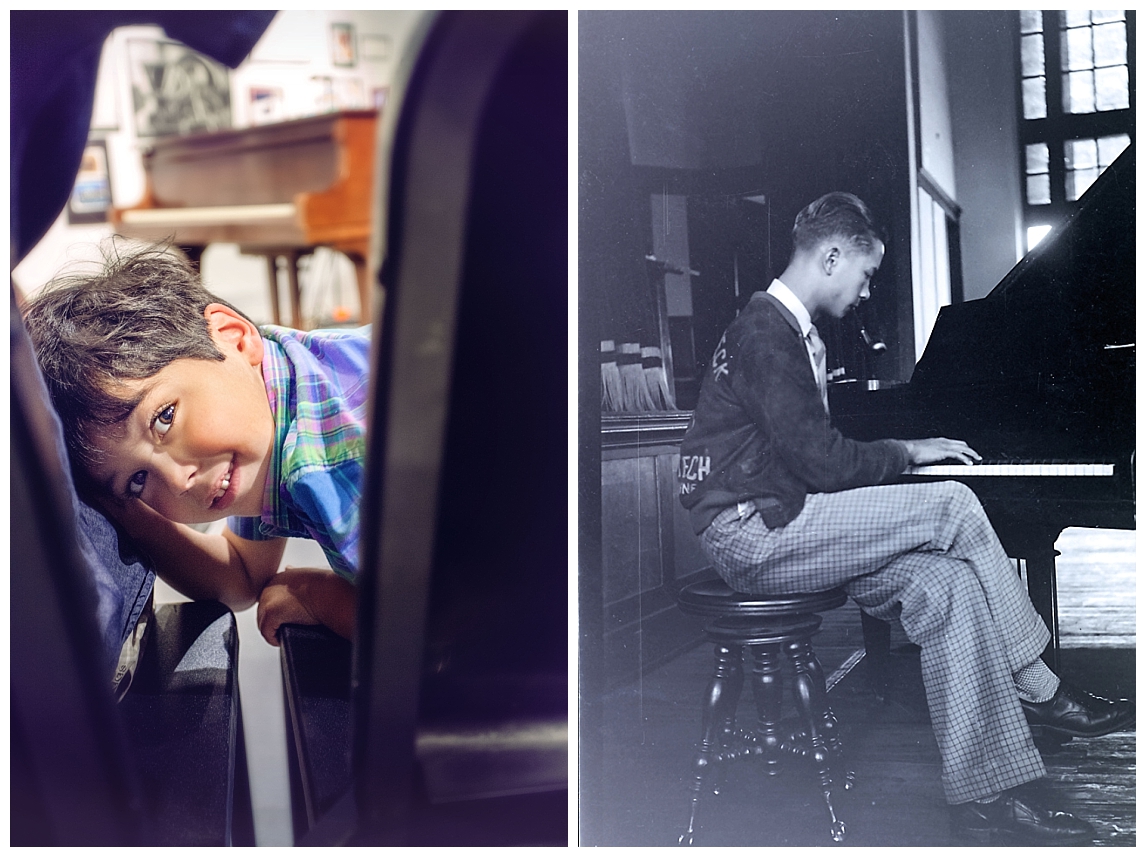

One thing my nephew, Michael, likes to send since Dad died is music. Often, I will open my email inbox or text app and find a link to a jazz piano virtuoso like Jesus Molina, below, with no explanation, and none needed. We both know what’s going on. Dad was a great pianist and he passed his love - if not his immense skill and dedicated practice - to both of us. Neither of us plays as well as Dad did, but we get by. Michael plays better than I do. He also plays in the improvisational style that Dad did. I have recently rededicated myself to lessons and am constantly striving to improve myself, but I sometimes joke that while I might sound pretty decent, what am I really, but a trained monkey? Anyone can read the notes.

But you see, Dad didn’t need notes. True, he was classically trained, despite his father’s wishes. The Chinese patriarch thought that piano was for girls. But my aunt GG, who was enthusiastic enough, had a wooden ear, and could play anything you put in front of her, but sounded like some kind of Model T-1000 Android doing it. Meanwhile, Sini, the second oldest girl, sighed and moaned through lessons. All Dad could do was smolder and yearn in the corner. When Sini finally announced imperiously that she was through with piano, Dad turned hopeful and pleading eyes to his parents, who - miracle of miracles! - grudgingly gave in to their son’s emasculating impulses.

Dad must have been not only a brilliant but a determined student because he had learned Liszt’s Liebestraum No. 3 by the time he was a teenager. It starts off simply enough, but don’t be fooled. The piece requires a virtuosic ability that few humans can aspire to. And what do you think he did with that raw natural talent for classical music? Well, in time, he turned his back on it. I never heard him play a classical piece in my life. Imagine being able to play Franz Liszt and never doing so! O cursed fate of mediocrities, to witness such a thing.

Dad’s soul required something altogether saucier and more invigorating. He sought out Harlem Stride, ragtime, old standards and improvisational jazz. And because there was no one in white society who respected “that old jigger music,” nor could teach it, he was completely self-taught. I get chills just writing that.

From there on out, he didn’t need notes. Heck, he didn’t even need a piano! Any flat surface before him would do as he riffed with strong and elegant fingers on the dining room table, on the steering wheel at a stoplight, or waiting for food at the diner. Because he was usually humming along in a low, gravelly voice that seemed to well up from somewhere very deep inside him, you could follow along with the melody, but he wasn’t doing it for you. It was spontaneous expression and it was part of who he was. Music was like a bodily function for him; it coursed through his veins like lifeblood, and inhabited his body fully.

He lost his virginity under a piano when he was 14, which isn’t exactly material to the story, but a fitting little piece of trivia. And I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that in the end, music saved his life.

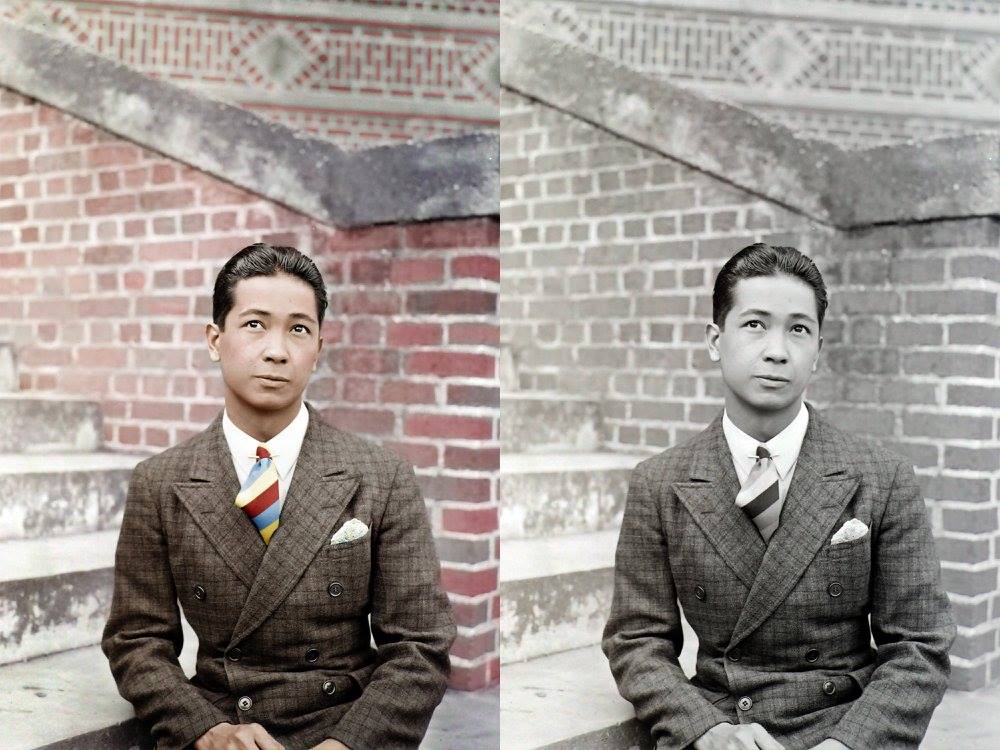

Earl Chan, College Man 1933-1940

Dad entered college as a Freshman in 1933, at the age of 20. He had had to work two more years to save up enough to go at all, and he continued to work through school - boxing (undefeated, 33 and 0); ROTC; a day of waiting tables, which ended with him throwing a nickel tip back in a customer’s face and telling him to go get a hair cut with it.

Before long, he was also playing musical gigs with his newly formed band “Robbie Chan and the Georgia Five.” They played private parties, school dances, community socials, and though he was on piano, there was little doubt - from his look to his talent to his overflowing charisma - who the star on stage was. He made frequent appearances in the gossip column of the school newspaper, called The Technique - “harmonizing” with girls, “casting amorous eyes at” girls, “dancing” with girls, “capering about,” “breaking,” and “celebrating in a big way.”

“With the idea of becoming God’s gift to the fairer sex, Earl Chan, that intrepid scholar, danced hither and yon at the Anak dance last Saturday night, breaking here, capering about there, and really celebrating in a big way. ”

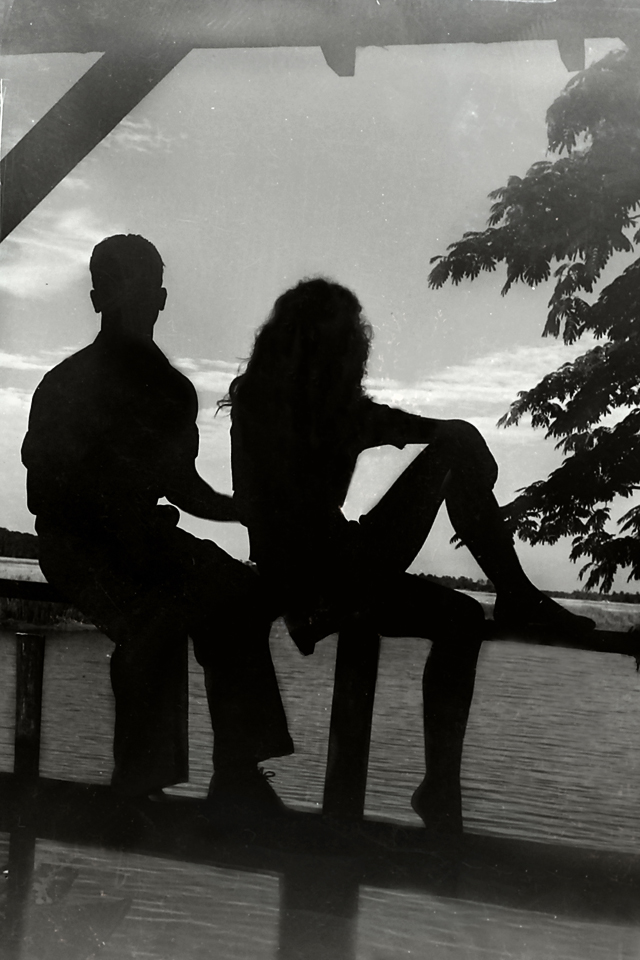

In 1939, he met Gretchen Best, who was also a college student in Atlanta, and he never looked at another girl again. They were married on Christmas Eve, 1941.

The War

While fighting overseas, in the China-Burma-India Theatre, the opportunities to either play or to listen to music were drastically reduced. But music, or the lack of it, was a frequent topic in his letters back home. He seemed to soak it up when- and wherever he could, like moth to a flame, and to shrivel a little at the shadow of the musical life he had led back home. Instruments were hard, but not impossible, to come by, and he showed ingenuity in building a make-shift radio for him and his men from a downed Japanese airplane. His only complaint was that he had to share musical tastes with everyone around, which he did not. Read some excerpts from his letters on the topic below.

December 9, 1942

Dearest Gretchen:

Last night the colored soldiers aboard had an old-fashioned songfest which took me all the way back home. In going to and from the dining room we are compelled to go through their quarters, and it was there that I stopped while some 25 voices harmonized in Roll, Jordan, Roll; Old Kentucky Home; Ain’t Guine Study War No More. Most of those who were not singing were pretty sick boys, as attested by loads of regurgitated food in buckets, on beds, and on the floor. One sergeant with whom I spoke protested that he is a land (emphasis on land) soldier, and “sho’ will be glad when dis trip is over - ERK, ERK, ERK” (that last was the pork and butterbeans he’d had for lunch).

I’ve got my sea legs after 2 days, and have not lost any of my food. The decks today were strangely less used than yesterday. In fact, 4 of the 6 boys in my cabin were confined to bed with bad cases of mal de mer.

A navy flying boat and a B-19 appeared today to circle around the ship and then fly off to the horizon. Other than a pair of herring gulls who have accompanied us, these were the only signs of life we’ve seen. Did you know that:

a) I love you for always?

b) the sea is blue - the color of your eyes?

TFNAA

Earl

January 20, 1944

[…] I forgot to tell you that I bought a portable foot organ while I was in the city. I’ve always wanted to play Cavalleria Rusticana on an organ, so I made the man throw in that piece. The organ has 4 octaves and a nice tone and cost 150 rupees. When I returned I discovered that other men did not ridicule me as I thought they would, but on the other hand were delighted. Two of the sergeants play - one with sweet harmonious chords, the other one half in dischords. But I now find that all the tender care I gave my organ on the trip back up over bumpy roads will avail me nothing, for tomorrow I move up and I can’t take it with me. I’ve sold it for what I paid for it to the sergeant who plays dischords. I don’t actually know, for I’ve only heard that mail goes up there only once every two or three weeks; today was my last chance to get any letter from you and none came - so goodbye, Beloved, until next month some time.

TFNAA

Earl

March 27, 1944

Beloved,

You wonder what I do on Sunday? Well, to tell the truth, I never know what day of the week it is. The days are not monotonous; each one brings a different problem with a different solution. Routine business may come in - then again I may go far afield for emergencies. But there’s no periodic recurrence of any event which would define any day as Sunday, or Saturday, or any of the other five. To me they’re just days - milestones in my journey back to you.

Back at base they have Sunday church services; here they do not. We have ‘em on any day of the week that the chaplain, who is mobile, comes around. This is about once a month, and you know that I wouldn’t go except for one thing - I have to play his little foot organ (4 octaves) which folds up like a suitcase. I want one when I return.

Dear, you must not think Peggy’s letter was strange. She’s loyal infinitely, and is the only friend I’ve got. From the time she started working for me, she has pulled me through a lot of tough spots, and will continue to do it as long as I call on her for help. She’d do anything for you or me or us; to me she’s been a godsend.

I love you,

Earl

October 18, 1944

Beloved:

Why ‘nell do I always have to have room mates whose taste in music runs a la jazzbo Pruhl [sic]? If I knew then what I know now, I never would have got this dam’ radio. When Bohannon and I were on reconnaissance we found a jap airplane which had been knocked down. The radio was intact, so we took it, we “acquired” a speaker from the signal Corps so we could have music. Or so I thought. I should have seen the “jive” look in their eyes when I brought it in. You know the rest in general. Specifically: a) Last night they turned off Abe Lyman, who was coming in clearly, in favor of Gene Krupa, who came from a station full of static. Thank goodness he was so far away I could hardly hear it. b) We got in on the very beginning of the Student Prince. You know, Deep in my Heart, and Overhead the moon is Beaming. They hawked that right off the air and got a program of all Glenn Miller recordings. They couldn’t put up with “all that talking and slow music.” Dam! Double dam!! I can’t do a thing about it. Pull my rank? No, Dear, I can’t ever do that and you know it.

Albeit, I have a good bunch of sergeants. Their theme song is “you’ll be with us in apple blossom time.” They sing this when they want to deride my audible musings on how long it will be before I take off for home. […]

November 21, 1944

[…] I have good music on the radio tonight, everybody has gone to the show, so I’ve been able to choose my programs. Right now they’re playing Silvia; this piece followed selections from the Chocolate Soldier, and there’ll be other similar music in the 20 more minutes this program is scheduled to run. I miss our Lux plays; but all in all, there are some really good programs here. British music is good because even their popular pieces have not yet degenerated to the Glenn Miller sub-level. Jap programs are always excellent; we not only get side splitting amusement from the dam’ lies they tell - we also get good American music designed to make us homesick. But the music misses its mark - we’re already homesick and the music only tends to cheer us up. We’re all grateful to Tokyo for these recordings.

Combat Headquarters called us up today and said we could come in and eat Thanksgiving dinner if we wanted to. They must have called up all the live troops in the vicinity ‘cause the mess hall was crowded when we arrived. But I didn’t mind the wait - they had fresh turkey and all the trimmings and I think I overstuffed, ‘cause my tummy feels tight now. I want to eat with you again, Honey. I won’t really enjoy anything any more until I can do that again. I’ve just been looking at your pin up picture, and I’ve got to hand it to you for knowing how to make me hurt […].

January 4, 1945

[…] We’re getting some mighty fine music on our jap air plane radio lately. Back up the road the Special Service people established a radio broadcasting station which they call “Halfway House”. The boys who made up the studio orchestra were all dam’ good - former professionals. But you can well imagine the noise they broadcast. Praise Allah! Halfway House has a range of only 50 miles, and now we’re four times that far away. The only stations we can get are in French Indo China, Shanghai, and London. The British can swing out too, but it’s the nice swing which antedates boogie-woogie by 6 years. The japs, in trying to make us homesick, play the same type of music. So my enlisted men may protest the tameness of the music (they’d like Glenn Prahl’s records) but they can’t do a thing about it. Tonight we have an all Fritz Kreisler program, they are now playing Liebestod and I wish you were here to listen with me. Better still, I wish I were there to listen with you. […]

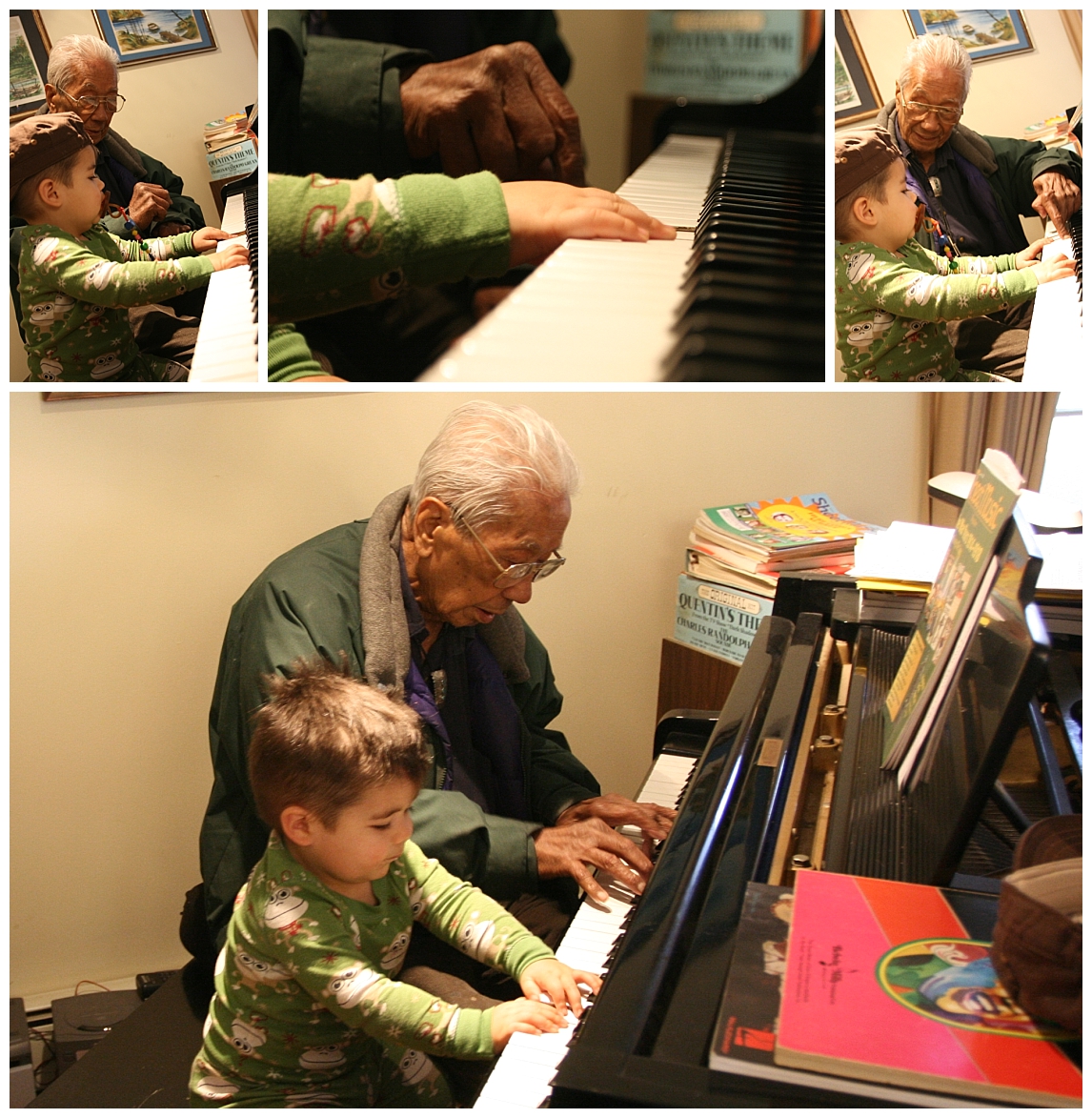

Paying it Forward

Dad’s piano playing was the soundtrack to my life. I often brought my dolls with me under the piano while he played. While I constructed elaborate scenarios, and sometimes used books and other objects to create “houses” and “rooms” for my dolls, I could hear the soft mechanical workings of the pedals behind me, the wooden thumping of the hammers above me, and above it all, clear sweet melodies that surrounded and inured me, temporarily, from all stress, strain or cynicism, all disappointment, fear, or worry. I saw Dad from the knees down and knew that I was safe.

He was often playing when I went to sleep at night. Many were also the nights that I awoke hours later to the sound of music flowing through the house again. Dad never seemed to know what time it was. Either that, or he didn’t care. He played as heartily at 1:30am as he did at 4:00pm, sleeping people be damned. It was just the way it was. Sometimes Dad had to play.

I started taking lessons myself when I was nine. I didn’t know it at the time, but this was the way that Dad gave gifts. He wasn’t much into “things.” I can count on one hand the number of “things” Dad gave me over the years - a beautiful pen; a wall mirror that he had made in his woodshop because I asked him to; my exquisite Victorian doll house; a book case with adjustable shelves; a well-stocked tool box…. Even at Christmas and birthdays, and even when the tags read “Love, Mom and Dad,” I knew from the way he leaned sideways to get a good look and was as curious and interested as I was to see what it was that Mom was the one doing the shopping.

Dad’s way of giving gifts was to offer you the opportunity to experience something that had been important to him - not just something that was “fun” or that he had “enjoyed,” but something that touched or affected him deeply. Looking back, I understand now just how abundantly he gave: piano lessons, horse riding, photography, skiing, swimming and diving, fishing (although I wasn’t a very gratifying student on that count), storytelling, world literature, a passion for travel, and of course higher education. He made sure we - my brother and sister and me, his grandchildren - had an opportunity to fold these things into our lives too, if we wanted to. He wasn’t just trying to schedule us; this was reverent gift-giving in its purest form. Each of these things had, in one sense or another, been transformative in his life. He was so eager to give us the tools to transform our own.

The Language of Love

In early July of 2015 we were driving home to Rochester, NY, to see Dad in rehab after he had had a serious fall in the bathroom and gotten a hematoma on the temple and cracked some ribs. We had also conspired with Michael to fly in from Oregon with his son, and dad’s great-grandson, Owen, as a surprise at the end of the week. I was looking forward to the reunion and the surprise, even if the catalyst was less than ideal.

My phone lit up with “DAD” on the screen and began to buzz.

“Hi, Dad!” I said brightly. “We’re on our way to see you. Only about six more hours. Maybe we can have dinner together tonight.”

“Honey?” he screamed. “Alexka?!” My stomach fell to my feet.

“Dad, what’s the matter? What’s going on?”

“Honey, you’ve got to help me! They’ve locked me up!” There were loud scuffling noises as he fumbled with the phone. He had lost the use of most of his fingers, including his thumbs, by this time, as the tendons in his hands had mysteriously seized up over the course of the last several years, a condition called Dupuytren’s Contracture. He made adjustments with each new loss in dexterity, but earlier that year he had found he could no longer play piano with his little “T-rex claws” and it was a devastating blow.

Suddenly he was back. “I’m in prison” he cried, hysteria tinging his voice and making it shrill. Cold prickles ran down my spine, and I felt sweat appear under my arms.

“No, Dad.” I was floored, paralyzed. My mind reeled trying to figure out what was happening. Dad had little “forgetfulnesses” at this point - he was nearly 102 - but he was an entirely lucid man. “You’re not in prison,” I told him. “You’re in rehab right now. You fell. We’re coming to see you; we’ll be there today.”

“I’m telling you, call the police!” his voice rose to frenzied pitch. “They’ve got me chained to the toilet, honey! I’M IN CHAINS!!! HELP ME! I NEED YOU!”

“No, Dad. It’s not true. Let me talk to the doctor. Where is the doctor? Can you see him?”

“FOR THE LOVE OF GOD, YOU’VE GOT TO COME GET ME. If you won’t do it, nobody will!” Then more scuffling, a muffled thud, and the line went dead.

“Dad! DAD!!!” I called him back but no one answered. I looked at Brent and fought the urge to scream, “FLY, YOU FOOL! FLY!” But what good would that do? We had six hours of highway ahead of us and two kids with round eyes in the back seat. I clasped my hands in my lap with a death grip and pressed my head to the window glass, squeezing my eyes shut, stifling my sobs, and pleading for strength and, above all, speed.

When at long last we bundled through the front doors of the Hurlbutt Nursing Home and Rehab Facility, me speedwalking in front, we found that the episode was past and Dad was quiet in his bed, but he looked like hell.

Most horrifying to me was not the brutal black bruise that covered most of the side of his head, but his hair. This man had never had a hair out of place in 100 years, and right now he looked like a kitten whose fur had been licked forward in all the wrong direction by its mother. His hair, more than anything, told me how serious this was.

The nursing staff told me about hospital delirium or psychosis, and that it was common for elderly patients to become unmoored when their physical surroundings are suddenly changed. He was calm but not thrilled to see us - mostly because I was the only person he recognized at the moment, and he had come to believe that I had left him to the wolves that day. He slid his eyes sideways to meet mine in a grim look of grievance. No one in the room but I knew the volcanic rage that smoldered under such a look. The boys, however, did understand immediately that the grandpa they knew was not there and pain blossomed in my chest as I saw them pull back.

Suddenly, and perhaps drawn to the cluster of new people in the room, his roommate - a dapper, well-coiffed gentleman in round spectacles, a tweed jacket and vest with plaid bow tie and a white dress shirt hanging half-way down his thighs - shuffled over to Dad’s side of the room and asked him why he had stolen his pants again.

Chaos ensued. Dad leapt back to life, yelling “Now you listen to me, you son of a bitch! I didn’t take any goddamn pants!” The addled professor - the nurse told me he had been a Russian university professor - shook his head worryingly and tisk-tisked at Dad’s potty mouth; then went to Dad’s closet himself and started to go through his clothes, looking for the missing pants. Dad was sputtering helplessly on his bed like a kid in school trying to tell the principal he hadn’t done anything wrong; in his drifting mind, these were serious allegations and his reputation was on the line. The Colonel and the Professor, both half-naked and arguing over missing pants. It sounds funny, perhaps, but at the time, I clenched my jaw tight - tighter - to keep my composure.

The good news was that by the time we left that night, Dad knew his two little grandsons again. The next day, and every day after that, Jin and Seu went with him to his stationary bike session, urging him on to hit the numbers he needed to be allowed to go home. They drew a picture of his boxing gloves, saying “Knock ‘em out grandpa!” in big crayon lettering that he could hang on the wall above his bed for inspiration.

We spent a week there, gently coaxing him back from the edge of the abyss, back to reality. On Friday, I came in at lunch time with his favorite - a bag of cherries. I put a handful in a Styrofoam cup and brought them over to where he was sitting in the common room.

“Welp, life isn’t always a bowl of cherries, Dad,” I said, “but that doesn’t mean you can’t have a bowl of cherries!”

This was exactly the kind of clever little banter that Dad loved, defined him in a way, and I saw his body perk up and respond to the familiar rhythm of “witty repartee.” And he laughed! Hallelujah! One step closer, back to himself.

While he happily slurped on his cherries (everything is harder with T-rex claws), I looked up to see Michael tip-toe around the corner behind him, nervous anticipation on his face. He didn’t know what to expect either. Tears of happiness sprung to my eyes. Dad struggled to turn in his seat to see what I was looking at, stared for a moment, confused, and then shouted “Oh you son of a gun. Michael! Come here, my boy! Come over here! Sit by me.”

“Hi, Grandpa Earl. I heard you got in a fight with the floor.”

Dad howled. It was heaven. Owen stepped forward and got reacquainted with his great-grandpa by showing him his new camera he got; and then all three boys - Owen, Jin and Seu - got reacquainted with each other; and with each meal, each day, each conversation, Dad’s psychosis faded further to the background.

On Michael’s last night in town, we went to the home’s large dining room, where there was an old upright piano in the corner. Owen wheeled Dad over next to the bench, while Michael took a seat. He figured that a Georgia boy must need some Georgia music to make him feel better, and he just started to play. Stumbling a little without music and breaking off repeatedly to say “it’s been awhile since I practiced,” he still managed to get out some skilled and lively renditions of “Georgia On My Mind” and “Sweet Georgia Brown,” among others.

The love was palpable, and I knew that night, that while Dad still had a journey ahead of him to get back home, and fully back to himself, everything was going to be alright. And it was. Dad loved music his whole life and made it one of his dominant gifts to others. It was so fitting that in the end, when he had lost his own, we were still able to hear the music in his heart and give it back to him.

Dad never lost his taste for singing bawdy little tunes from his days in the college glee club - the more clever and off-color, the better. Get him a kazoo and you’d really have something to write home about. As a young man, I know from the stories that his music was seductive. It beckoned and promised, and lured his listeners with whispers of their own daydreams and illusions. These they could project on to him and imagine him anything they wanted him to be, even half-divine. No wonder he was so popular.

But when I knew him his piano music had more sorrowful, nostalgic strains that seemed to contain a lifetime of yearning and mystery. He became stoic in his demeanor, a transition that pictures suggest was tied to the war. Although always a conversationalist, he did not often share deep sorrow or pain, and I only ever saw him cry three or four times in my life. The first time was at the death of his brother, Sandor. The hollow thud of an earthen clod hitting the coffin lid rang out, and he took in a sharp, ragged breath. “Oh boy,” he said, looking down into his fingers laced at his hips. “I never really felt it till now.”

The second time was on my wedding day. He looked like the Godfather, never taking his sunglasses off the whole time. Mom told me afterwards, whispering it conspiratorially into my ear, that she had had to remove a damp piece of Kleenex stuck to his cheek partway through the ceremony.

The third time I heard him cry was when I told him over the phone that I had lost my first pregnancy and his voice quavered and broke for me. He had been certain it was going to be a girl. I said, “How do you know?” and he said, “Well, what else could it be?!”

When Mom died, he was beyond tears and they never did come.

And the last time I saw him cry was at the end of his life, when he tortured himself over whether he had really needed to kill a particular Japanese soldier he had “picked off” one day when he saw him floating in retreat down the Irrawaddy River, hiding behind a log. “He was just a kid!” he sobbed. “What if he was just trying to get away, and I killed him?”

Victor Hugo wrote, “Music expresses that which cannot be put into words and that which cannot remain silent.” I have come to believe that Dad’s music spoke for him when words failed. He played with an emotion that could be heard only with the heart, and if it caught you unawares, the sweet melancholy could make you weep.

When Dad died and we were planning the memorial, I was surprised to see a person I didn’t know on the list of speakers. It turned out that the woman was the daughter of a man who had grown up as a boy on Dad’s street in Scottsville, the same street I grew up on a generation later. The boy had lost his own father - to an accident or illness or maybe even to the war, I do not remember her saying - and Dad had seen the boy and befriended him. He taught him how to ride a bike and take pictures and to fish; to do a little boxing and mechanical work on the car. The boy - now a man - was, ironically, in Dad’s home town of Savannah, GA at the time of the memorial, away on business. He had heard of Dad’s passing and had called his daughter, telling her she must go and speak. She read his prepared statement and although she had never met Dad in person, seeing what he had meant to her father made her emotional. My memory is hazy on the wording, but I remember the feeling. He urgently wanted people to know that Dad had saved his childhood, made him understand that it was all going to be okay. He wanted us to know that Dad was like a father to him, but one who also taught him how to remember his own dad in healthy and healing ways. He didn’t know what would have become of him if Dad hadn’t seen that lonely boy and known he had needed a friend. He ended with a memory of what it was like to live on Oatka Place. I am paraphrasing:

“Bob’s lights were always on - always. And on summer nights, when he had the doors and windows flung wide, and the crickets were chirping, and the night was warm, and people were settling in to their beds, his beautiful piano music drifted on the breeze, over the rooftops of the neighborhood, and made everybody feel like the world was still a good and decent place; that there was still beauty here, and love.”

Only recently, in the wake of his death, as I’ve seen how I turn to the piano in my own darkest hours, do I begin to understand what those ivories did for Dad, and what that nostalgic yearning all must have meant. I know now that he didn’t just “love music.” He needed it. It took his pain and sorrow and cleaned it, handing it back to him as something beautiful and healing him - and everyone he played it for - in the process. I think that counts as at least semi-divine, don’t you?

“Music expresses that which cannot be put into words and that which cannot remain silent. ”

My own losses and disappointments pale when stacked against his. And yet I knew him primarily as a joyful son of a gun. I never understood until now how much of that was simply a decision to be so. Happiness, it turns out, is an inside job. It takes optimism, grit and discipline to not let yesterday’s failures, fears, grief or disappointments dictate today’s actions. It takes no discipline at all to lie down in defeat or to wallow. No imagination whatsoever to think the world colorless and tasting of ash.

When I think of Dad sitting at the piano, I think I hear him telling me this: Be disciplined enough to choose a good life, when- and wherever possible. It is always possible. And if you will let it, music can be your guide.

Orpheus indeed.

In Orpheus & Morpheus Part 2, we will see what happens when the God of Music meets the Master of Dreams: Morpheus - the shape-shifter, who could take the form of any man.

Like, Comment, Share!

Although the buttons below work, Squarespace is currently struggling with a bug that erases the tracking at random. Please don’t let low or no numbers shown deter you. Likes and shares still help boost my visibility, even if the numbers don’t stick around to show it. Thank you!