The Third Rail

Miss Van Doehren was scribbling numbers on the chalkboard at the front of the classroom in 3B when there came a rattling, brittle-sounding knock on the frosted glass portion of the classroom door. Principal Tipton eased it open a crack, grabbing the edge of it with one hand and slipping just his upper torso through. “Miss Van Doehren?” he said in a hushed tone. “Can we borrow Robert Earl for a moment? The camera man is here.”

I had been copying the figures from Miss Van Doehren’s chalkboard, but froze at the sound of my name. I looked up and from side to side, to see if anyone else had heard what I had heard. Miss Van Doehren - scrawny, plain, pleasant - turned to me and nodded with her head toward Principal Tipton. “Earl? You may be excused. You can finish up when you get back.” I stood up and laid my pencil in the groove at the top of my desk. A rushing sound began to rise in my ears, as my classmates rustled and a number of boys started “ooo-ing” good-naturedly, but I clenched my jaw and stared them all down, daring them to keep at it. Miss Van Doehren slammed her yard stick on the desk. “That’s enough, children,” I heard her say as I exited the classroom, not too hasty. “The newspaper is doing a story on Earl and his siblings,” she continued as I closed the door behind me. “Let’s all be supportive and curious when he comes back.” I barely registered her words, fading into the hallway ether behind me. Newspaper?

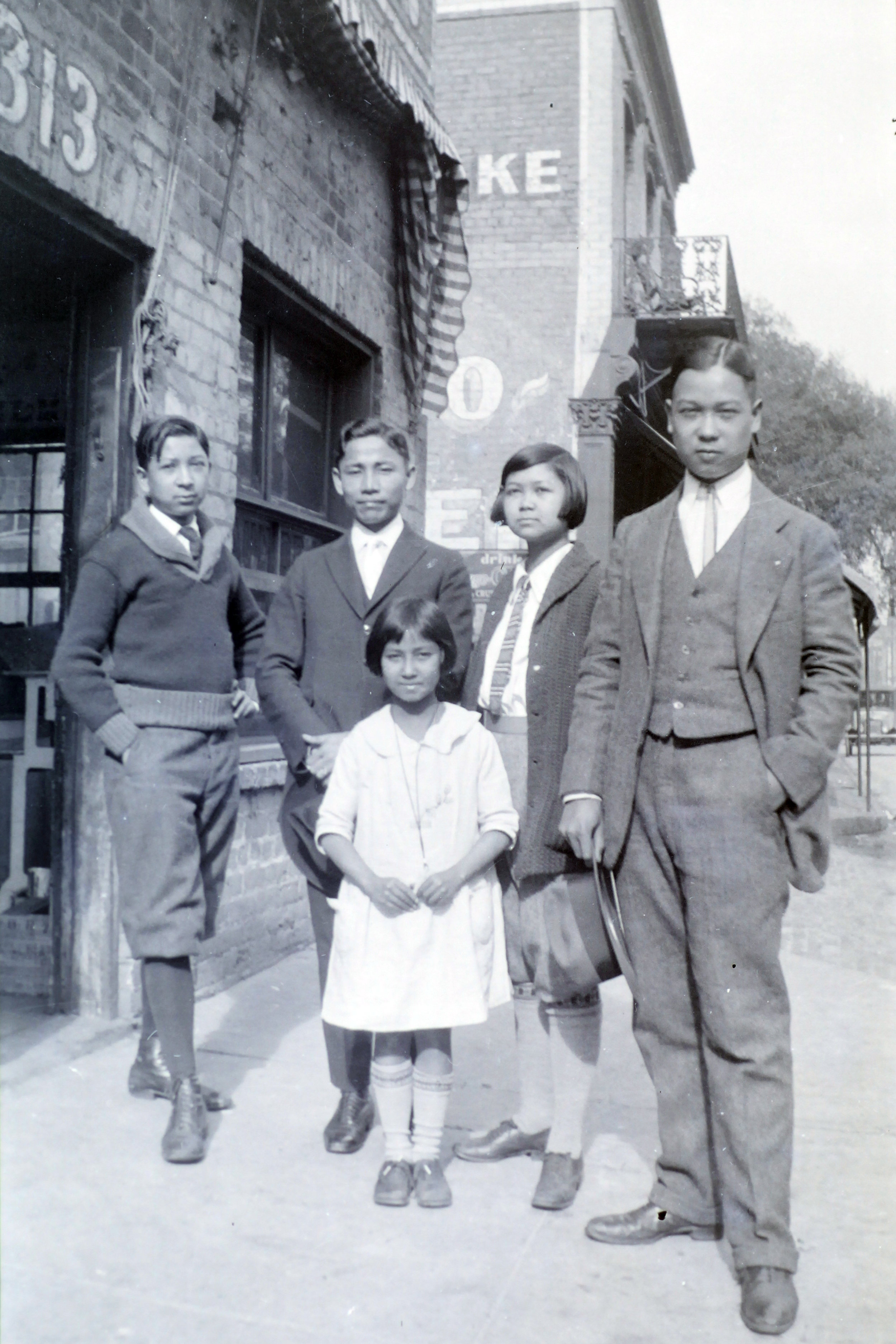

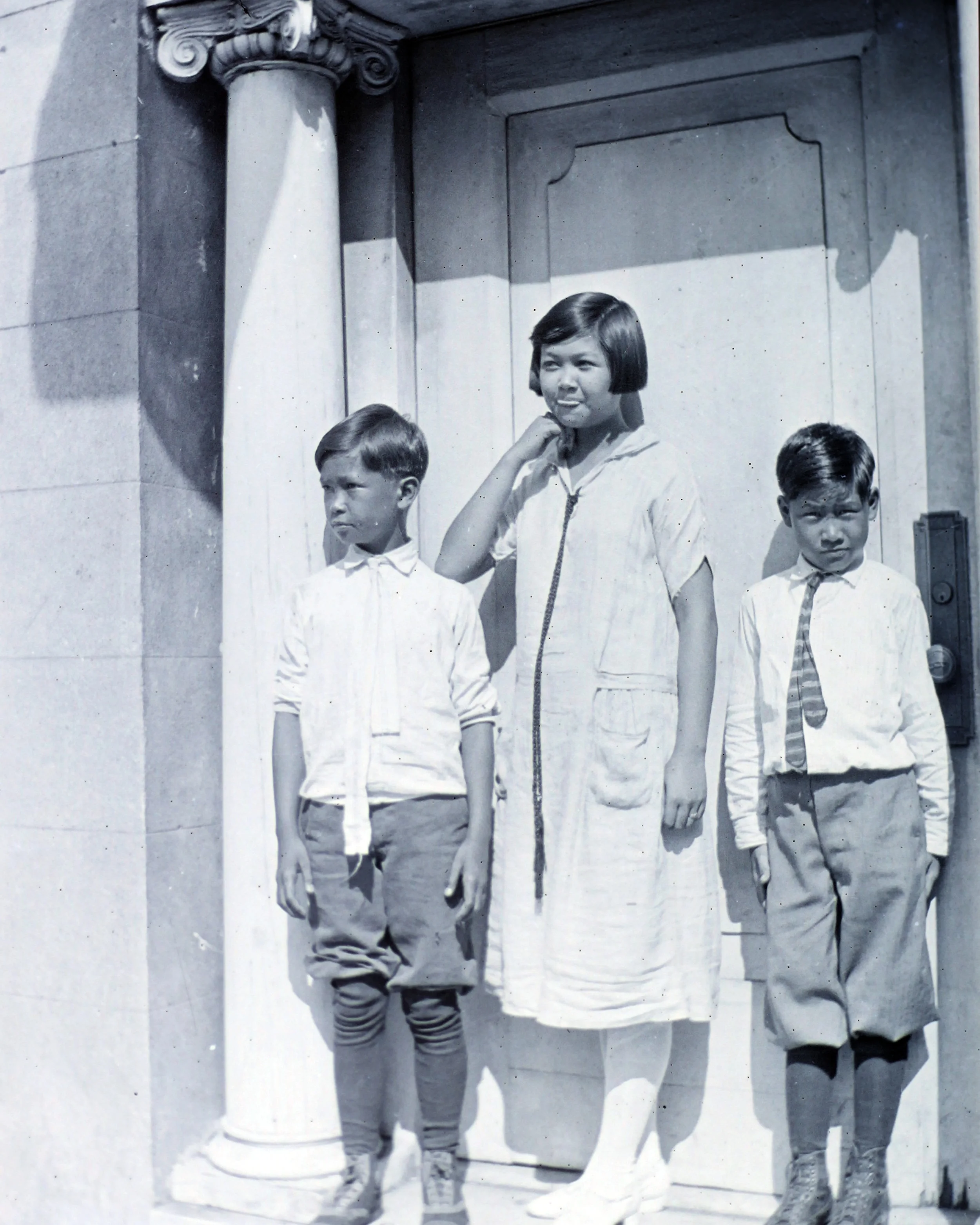

I followed Principal Tipton down the green and white linoleum-tiled corridor. The sound of rubber soles squeaking and shuffling reverberated off the white plaster walls and, safe from view of my classmates, I trotted to keep up. We exited a side door into a bilious cloud of bright and humid shade that, after the school’s inner gloom, made me squint and duck my head. My sister SinFah was there, two years older than I, as were my sister Gerald and brother, Sandor, both in the Savannah-Chatham County Junior High School. I did not at first perceive anyone else there except for a rather sorrowful looking cat with matted fur and a weeping eye, which huddled by the brick wall, in the lee of a trash receptacle, squinting at us disinterestedly. Once my vision equalized, I realized there was also a man in a straw skimmer hat there, holding a press camera slightly askew by the large bulb flash. A damp, wrinkled suit and crooked tie with a dab of mustard that had been wiped away at some point earlier in the day gave him quite the appearance of a vagrant. Only the camera suggested he was there by design. As the son of a laundryman, I couldn’t help but notice, No self-respect.

Principal Tipton shook the press man’s hand quickly, wiping his own afterwards absent-mindedly on the front flap of his blazer, and then set about arranging me and three of my siblings in a row. He took us by the shoulders and marched us sideways, this way and that, standing back to take in the effect, before finally settling on the most obvious composition - oldest/tallest to the left and youngest/shortest to the right. Sandor, Gerald, SinFah and Earl.

The press man took out a notebook from the inside breast pocket of his suit jacket and drew a pencil from behind his ear. “Okay,” he said, licking the lead tip, “so tell me one at a time your name and grade level.” He scribbled something across the top of the page and looked up when he was ready. Sandor said his name first, and the press man started to write but abruptly stalled, staring blankly at the space beneath his thumb and forefinger. “What was that now?” he asked, frowning slightly, as if he wasn’t sure he’d heard right. “San - do?”

My oldest sister said, “I’m Gerald,” and got another look, at which point she grudgingly conceded that her legal name was Gladys Geraldine. This is what the man wrote down, to her disgust and my own delight. At SinFah, he gave up all pretenses and dropped the notebook and pencil down to his thighs and looked off to one side in exasperation. I almost felt sorry for him. Almost. He seemed relieved when I told him my name was Earl. “Okay… E-a-r-l…C-h-a-n…. Smartest kids in the whole school, eh?” he asked, underlining something heavily twice and jabbing a period onto the page. For a moment, I wanted to jab that pencil onto his face. He looked up, shaking his head. “Ain’t that somethin’. That’s a real feel-good story. Our readers are going to love it.” He slipped the notebook into his pocket, and rolled the pencil back behind his ear. “Okay, you ready?”

Principal Tipton ran around behind us to take his place slightly to the side of Sandor. As an after-thought, he reached his hand out and placed it - stuttering at first, but then more firmly - on Sandor’s shoulder. “Smile everybody,” he said, peering around Sandor to make sure everyone was complying, and then stood tall and showed his own teeth broadly. The press man raised the camera to his face and said, “okay, everybody, 1, 2, 3…” I lifted my chin and looked straight into the camera. I’ll show you. The flash bulb gave a burst of light and then exploded with a percussive crack and a thin cloud of smoke.

Before

I was ten, and entering the third grade, when my brothers, sisters and I were invited to attend Savannah’s public school. I was too young to know that Georgia state statutes still called for segregated schooling or that my brothers and sisters and I amounted to a social experiment, confounding as we did bureaucratic definitions of race.

Prior to this, we had been tutored at home, first by Mr. Gregory - floppy-haired and reticent, a man in riding pants and boots, who, as far as I could tell, always arrived on foot, but liked to brandish a riding crop against his thigh or on table tops as we droned through spelling and conjugation drills. I was a quick study, rarely needing to go over anything twice. I spent lots of time swinging my feet or jiggling my leg under the table during lessons. I felt the hot prickle of the Georgia heat under my collar, and turned my head longingly to Mama’s kitchen window, which she almost always left open, hoping to catch a breeze.

According to my sister SinFah, though, Mr. Gregory was “ever so handsome” and so it was with great histrionics on her part that we eventually graduated from Mr. Gregory at home and started trekking through Forsyth Park, Sinnie openly sulking, to reach the doily-laden, mahogany dining room of Mrs. Latimore - old, chubby and slightly musty-smelling. I rather liked her, though. She was smartly dressed in tailored one-piece wool or canton crepe frocks, with frilled, pleated, scalloped, or otherwise ornamented collars. She had an affinity for checks and paisley patterns that seemed to me very fresh and young, and stood in intriguing contrast to her silver floss hair and thickening waist. Likewise, while she was always respectably coiffed in finger waves, everything gathered at the nape of her neck, I noticed that there was often a nimbus of unruly stragglers about her head that made her look perpetually hurried, harried, excited and/or slightly out of breath, whether or not she was any of these things. This effect was heightened by the natural bloom she still had in her cheeks, giving her the overall gestalt of a much younger woman than she was. She looked old, but felt young.

Mrs. Latimore smiled down her nose at me through her half-moon spectacles and liked to give me a look as if she had a funny secret and was pretty sure I was in on it too. I wasn’t, but I always thought I’d like to be.

Our new tutor, I was delighted to discover, cared almost nothing for drills. Her dining room, with the lace-curtained windows flung high, felt airy and expansive, as did the way she wandered lightly around the room with great billowing arm movements while she talked. While Mr. Gregory had had a very dour voice for such a young man, Mrs. Latimore - easily forty years his senior - seemed almost girlish when she spoke. Her voice never droned, but tripped and tumbled, increasing in speed and intensity whenever something was of particular interest to her, which it seemed like most things were.

The truth is, while I had been less good at hiding it, we had all languished under Mr. Gregory’s pedantry. I was quite sure, in fact, that Gerald was at least equal, if not superior, to Mr. Gregory in all the three R’s. We Chan children were bright, studious and respectful, as well as each other’s only school- and play-mates, and so there had really been nothing to hold us back but Mr. Gregory’s own stodgy notions. Or was it limited expectations he had had for us? It’s not for me to say.

Mrs. Latimore, by contrast, breezed through our lessons in reading, writing, and arithmetic, each at our own level, and as fast as we could learn them. And then it was on to geography and history, which really got her arms billowing. She had a chalk board on wheels that she would shuffle in backwards with each morning, and set up diagonally in the corner, in front of her china cabinet, filled, I noticed, with rather plain-looking white dishes. While we learned geography and ancient history, she drew whimsical depictions in chalk of the Pyramids of Giza, the Nile River Delta, the Sphinx, the Parthenon, the Colosseum, and one day, with extra care, the Great Wall of China. It was already drawn when we filed into her dining room that morning. My heart swelled, and I looked over quickly to my siblings. Archie and Sandor took a seat and seemed to be sitting a little taller, while Gerald and SinFah were openly grinning from ear to ear. We were six American-born children (my baby sister Bernice still at home with Mama), all spellbound by the romance of Papa’s homeland, and we felt kinged and queened for a day.

Papa spoke of the Cathay of his childhood as you would a beautiful dream. That may well have been what it felt like. Fleeing at the age of 19, Papa was ever the reluctant exile - quite sure he hadn’t had anything good to eat since 1889, for example, and shunned American cabbage as a useless, tasteless thing. “Taste like hay!” he would cry in dismay, every time as if it were the first. “Chinese cabbage sweet!”

Although he made a living laundering other people’s clothes and starching and curling their collars, it meant something to us that Papa was not “really” a laundry man. He wasn’t a very good business man either, according to my brother Archie who was a lot older than me and starting to learn how to run things. Too willing to extend credit to people who can’t pay, he said. But what did Papa know about business? His head was in the clouds. He studied philosophy (Confucius, Lao Tzu, Zhuangzi) and wrote poetry. He had won a poetry contest in the capital the year of his exile, and been carried in his home village, swaying and triumphant, on the villagers’ shoulders, notice in hand, to see his father, who was the village Schoolmaster.

Papa said he hopped to the ground, stumbling and grinning, and then straightened himself and composed his face to approach his father, who was not his father in public, but the Schoolmaster. And so it was the Schoolmaster who took the notice and scanned it, gave a terse nod of approval, and handed it back. Only Papa, who stood close, could see the glint in his eye that bespoke a father’s pride. It was one of the last times he saw his father and so we heard the tale often.

Papa had received a classical Chinese education and had meant to become a Confucian Bureaucrat and work in the Imperial civil service. It was what all the best and brightest young men of China did. But life had had other plans for him. The Empress Cixi was a tyrant and soon Papa found himself not trying to join the government but organizing to overthrow it. For his leadership, he was named and convicted in absentia and condemned to death by beheading. The tale of the murderous round-up of his village and his own violent escape gave me nightmares. It was hard to reconcile with the quiet grace of his slender frame, or the delicate way his hands held the brush when he painted poetry or laundry tickets.

And now, here he was, half a world away, starching and ironing shirt collars for people and helpfully forgetting to collect the fee. But he sang when he worked, and the laundry workers, who were all Negroes and mostly life-long employees, chuckled at him and shook their heads and called him “Boss” with a fair degree of affection. I reckon no one in the place ever set out wanting to clean and iron their lives away, and maybe there was a kind of kinship about that, maybe they understood each other. And Papa knew that dignity lay not in what you did but always in how you did it. “Remember you are a Chan,” he said, whenever we found ourselves in a morally ambiguous situation, as if that were the only guidance we’d ever need.

Papa held us in thrall with his tales when we were at home, but it was thrilling to find ourselves talking openly about China in the outside world, here, with Mrs. Latimore. Her effort and excitability hinted, I thought, at exotic longings a lot like my own. From what Mama said, Mrs. Latimore had been born and raised in Savannah and never been further than Charleston after suffering an early widowhood, but this seemed to have no bearing at all on her sense of wonder about the world outside. Indeed, if anything, it seemed to bank the fires of her imagination and make them glow. I pondered whether Mrs. Latimore might not see our five little black heads bent over her dining room table and think that she was quite on an adventure of her own making, though. Anyone could see that she enjoyed raising eyebrows, always in the most demure and respectful ways, of course. “Tutoring the heathen Chinee” would certainly have raised a few.

I pursed my lips in repressed glee. An image of my ebullient teacher had come vividly, and unbidden, to my mind: riding on a camel, tossing the end of a head scarf dramatically over one shoulder like one of the Three Wise Men, and looking rather regal doing it. Although she didn’t look the part in any way, there was a feeling about her that if, by some magic, she suddenly did find herself on camel back, or sipping strong coffee in a Turkish bazaar, she’d startle for only a moment and then quickly sink down with a conspiratorial smile and avoid detection for as long as possible, while she steeped herself in the guilty pleasure of doing what everyone expected least of her do. I liked that about her. I liked it a lot.

In Mrs. Latimore’s dining room, I realized for the first time that I loved school. I began to grasp just how wide and wondrous a place the world was and I wanted to see all of it. I imagined sending Mrs. Latimore picture post cards from each of my ports of call.

Dear Mrs. Latimore,

Agra is the bees’ knees. I am lunching on fresh mangos at the Taj Mahal. Do you know what a pangolin is?

Sincerely,

Your pupil Earl

I had never had a mango and never seen a pangolin, but at this point, was pretty sure I could identify either one if it ever crossed my path. She also introduced us to great literature. Reading - real reading, not Mr. Gregory’s drills - burst a window open on to the world for me. It was a revelation. Gerald had been reading Grimm to the three littlest of us - SinFah, me, and baby Bernice - for years, which held us transfixed. But Mrs. Latimore guided me toward The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood; The Life and Strange, Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe; and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. I read them voraciously. I had heard that reading was supposed to help one sleep, but when I had to put these books down at night, because I shared a room with Mama and Bernice, I often lay awake for hours. I couldn’t sleep for all the fierce and savage color, all the magic and swashbuckling magnificence: mountain peaks, ocean trenches, improbable beasts, enchanted forests, stunning feats of derring-do, cunning villains, clever heroes, and friends of the heart. I tossed this way and that, my body humming with expectation for all this world had to offer. Mama would turn over sleepily and pull me closely to her to calm my body, but my mind galloped on. By golly, it was a smorgasbord, limited only by my own imagination, I realized, and that was growing by the day.

A Million Dreams

One morning I shuffled to the kitchen and found Mama there alone. My coarse hair stood on end in a rooster tail, and flapped stiffly behind me as I walked. I had the strangest feeling in my chest - like soap bubbles or butterflies. I examined it for a minute and determined that yep, there was no doubt about it: I was excited about something. But what? I couldn’t say. “Mama,” I said, still with a frog in my throat, “I feel kind of excited right now.”

“Hmmm, that sounds nice,” she said, absently, while laying out the bowls. Barely taller than us children, Mama was small in stature but a great colossus in my view. She was gentle, she was kind, and she was beautiful, beautiful to me. She had a face that made me want to both stop in my tracks and run to her and lose myself. She was not Chinese like Papa. But nor did she look like the wives of Papa’s clients either. Actually, she never spoke about herself at all, and since we had enough to fire our imaginations from Papa’s tales of China, none of us ever thought to ask much. We accepted half-murmured statements about “California” and a “Spanish ancestor” and left it at that.

Papa often watched Mama move about the room with an inscrutable look on his face, and then with the heart of a philosopher-poet, would say she walked “like a little grass.” Mama, who had heard this innumerable times because it was just his way of saying “I love you,” would chuff in amusement and wave his statement away, which was her way of saying “I love you, too. Not in front of the children.” This might then encourage him to stand and give a perfect impression of our mother’s bouncing and swaying little gait, showing us just exactly how a blade of grass might look if it decided to uproot itself one day and go for a walk.

I approached her and pressed on. “But why do I feel excited when I don’t even have anything special to do today?” She stopped what she was doing and reached for my cheek, face shining, and slid her fingers down to my chin, lifting it to get a good look at me. I was surprised to see her eyes glistening with sudden emotion. “Oh, Sugar, that’s just what you call being happy to be alive.”

Gerald read all the books I did, and did it about twice as fast. She soon called for a daily game of Robin Hood and his Merry Men in Forsyth Park during our walk home from Mrs. Latimore’s.

“I want to be Robin Hood!” I yelled. My mind had just leapt about ten adventures into the future at the mere mention. Planning was well underway when I was pulled sharply back to the present.

“You can’t be Robin Hood,” said Gerald. “I’m Robin Hood.”

“But you’re a girl,” I frowned.

“Listen, Oil Can - it’s my game,” she said, snorting at her own joke, knowing that it drove me batty. Earl Chan lent itself well, I suppose. If it weren’t my own name, I might have laughed too. I had once thought of a clever retort by calling her Glad-Ass (a double-whammy because it played on her most hated name to begin with) but I quickly learned that while she might be a girl, there was still a pecking order, and I was at the bottom of it.

“Don’t call me that!” I fumed and retreated into disgruntled silence.

“OH!” Soon my spirits were rising again. “I’ll be Little John,” I cried. I threw my chest out and turned this way and that to survey the imaginary landscape for footpads and cutpurses. I could knock a man out with a mighty back-hand blow! What would it be like to see the world from Little John’s heights? How long would his stride be? I stuck one leg out and stretched it as far as it would go and took one and then another giant leap. I turned back and was going to do it again in the other direction when Gerald laughed.

“You can’t be Little John, silly!” she said.

“Why not?” I asked, my chest deflating again, this time real anger starting to prickle at my ears.

“Because Little John is huge and you’re little.” Again, I found it hard to argue with her on this point. And so I contented myself for the time being with first one then another of the lesser merry men - Will Scarlet (a great swordsman), David Doncaster (a loyal friend). These weren’t bad, really; quite respectable, actually. But then one night I discovered Gilbert Whitehand, who was a skilled archer. Together with Robin Hood, they were reputed to be the best archers in all of England. At last I had my man!

That night, I lay awake again, imagining myself not only hitting the bulls-eye, but then the arrow in the bulls-eye! Shooting the Sheriff of Nottingham’s arrows right out of the sky! I heard Mama’s slow and even breaths beside me and I closed one eye, held my thumb up in the air, and focused on a small water stain on the ceiling above my head. “Pewww!” I whispered to myself.

One thing was clear. I needed a bow. But how? Could I make one? I started mentally sorting through the materials I would need. It couldn’t be one of the fallen branches we saw lying here and there around the park; those were brittle and would snap. I needed something supple….

The next day, which was a Saturday, Gerald fashioned herself a newspaper hat with a paper feather, and I made myself a bow from a spring branch I cut from the althea tree in our little walled garden and some twine from the laundry. It took some trial and error, but I eventually figured out that if I notched the ends of the bow, it made it much easier to secure the twine there, tucking one end into the notch, and wrapping it several times around the top and bottom and slathering it with glue to hold. I put notches in my arrows, too, whittled from scrap wood taken from out back, so that I could fit them onto the bow string. My first test shot traveled several feet and was reasonably accurate. I was pleased as punch and Gerald borrowed the Kodak to take my picture.

Gerald and I, Robin Hood and Gilbert Whitehand, prowled the park and took cover behind the ornamental light posts, commando crawled through azalea bushes, and crouched behind park benches. Friendly, gentle Mr. Reilly, the policeman who patrolled the park, was appointed High Sheriff of Nottinghamshire. By Gerald, of course, even though no one could have been more out of character than this kindly Irishman in the role of the hated King’s Sheriff. Dear Gerald – she always got her way.

Gerald wore her hair in a page-boy cut that didn’t catch in the branches, and often put on Sandor’s short pants like mine. Sure she drew looks but she didn’t care one wit. “I knew from the start that boys were considered better than girls,” she said to me one day, breathing heavily on the ground next to me. “And if I can’t be a boy,” she ran in a stooped trot across the path to crouch behind the bench across from me, “at least I can have a boy’s name and wear pants when I want to.” She had no patience for skirts and bows, or for that matter, sewing, cooking or dolls either. We both rolled our eyes at SinFah’s prissy antics, so moody, so boring. Gerald was a bookworm and an adventurer like me, and it is no surprise that, even three years my senior, she was my favorite playmate.

On these walks home, Archie, our oldest brother and almost done with schooling, usually ran ahead to get back to the laundry on Whitaker Street, where he was expected to work until supper time. He didn’t like the stories as much as we did anyway. His big passion was the circus, and any time off from the laundry would find him out at the carnival grounds by the big tent, if it was in town, or otherwise painting and cutting figures for his home-designed flea circus. A budding business man, he charged neighborhood kids a penny to come and see it, which they gladly paid, and stood in line to do so.

Sandor, second oldest, would soon have to follow into the family business, but sometimes still took a turn as the Sheriff of Nottingham. He did so offhandedly, though, and mostly when he determined that to do so would foil and annoy Gerald. He was the trickster in the family, but always gentle, never mean. Meanwhile, Sin Fah might ordinarily have liked to play Maid Marian, if her older sister weren’t always Robin Hood. “What’s romantic about that?” she had railed. So she usually walked at a distance from us - far enough away that she didn’t really have to play, but close enough that she could follow along and snipe criticisms at us about what we were doing wrong. Bernice at this time, the littlest, was still at home with Mama and she looked so cute when she ran to us.

Two years on, we learned that we were finally going to go to school with other children - white children - and it was time to leave Mrs. Latimore. Mama and Papa came to collect us on our last day, a bright and balmy May afternoon, and brought with them two tea bowls with saucers, in thin, cool porcelain - lightening to translucence at the rim - painted in long life and medallion rose pattern, a gift for her kindness and the great skill and care she had taken with us.

Papa presented her with the tea bowls with a little bow. Mrs. Latimore’s face was bright with emotion and she fussed embarrassedly over the delicate things, like eggshells in her palm, priceless treasures. Papa helped her give them pride of place in her china cabinet, central spot of the middle row, popping beautifully against her plain whitewares. She stood back, with hands at her cheeks, shaking her head in delighted disbelief. She looked gratefully to Papa, reached a hand out to Mama’s arm, and then cast her gaze over each of our six dark heads and blinked her eyes as the color rose up in her cheeks. She cleared her throat before speaking. “Mr. and Mrs. Chan, the honor has been all mine. What an adventure it has all been. You have no id-….” She took a deep breath and finished, “You have curious and delightful children. I know that more regular schooling will take them far, and I can only imagine what they will bring to the classroom and their new classmates. I will miss them all greatly.”

”You hear that, children?” she said turning to us, and stroking my hair with her palm because I was closest to her. “Don’t forget poor old Mrs. Latimore. Come back again for tea and cookies and tell me everything’s that new.” I was sad to go, and I don’t really know why, but I never did go back for tea and cookies.

Papa, the Goodwill Ambassador

Papa had included the tea bowls in the Chinese Christmas Box he ordered from Guangdong for us every year. More of a crate than a box, it usually stood about three feet by four and was made of rough wood, and sealed with oiled paper to keep the moisture out. Covered in large Chinese brush characters, and often taking months to reach us, it arrived looking well-traveled, a magical dispatch from a lost fairy realm.

To open it, Papa would have to drag it into the large laundry room in back of the store, and pry up the lid using a crowbar and hammer. We danced on our toes and jockeyed for proximal position when the lid came off, whereupon all six of us would dive simultaneously in and tear the packing to shreds, sending great tufts of straw and Chinese newspapers flying, littering the concrete floor at our feet between the wash tubs.

Inside the box, on the top layer, were silk handkerchiefs in jewel tones of turquoise, jade green, rose, and purple, exquisitely embroidered at the edges for the ladies. Then came over-sized white ones, sturdier, more masculine, and with wide hems as was appropriate and stylish for business men. There were delicate ladle-like soup spoons, chopsticks housed in individual silk bags, tea bowls, saucers, and vases. None of these treasures was for the family, of course, but tokens of appreciation that Papa distributed to prominent Americans - judges, lawyers, government officials - who had shown kindness, support or aid to Savannah’s Chinese; to loyal patrons; and to personal friends. Papa was the acknowledged leader of the city’s Chinese, and he took his good will ambassadorship seriously, always dressing impeccably in the most up-to-date and modern fashions, running a tight ship at the laundry, and going out of his way to make friendly connections with the city’s luminaries, as well as civilian and business communities. Certainly Mrs. Latimore, who had undertaken the liberal education of his six children for years, was exactly the kind of person he wanted to honor.

Underneath the gifts of good will, were things for the family: colorful and fragrant tins of Oolong and Jasmine tea, and wonderful things to cook with - water chestnuts, bamboo shoots, dried mushrooms, and always, at the bottom, a large, coarse earthenware jug of soy sauce, corked on top and sealed with red wax at the spout. Our mouths watered. Other things, which Papa held up with especial appreciation, we wrinkled our noses at, like salt fish and month’s old duck eggs. But there were treats in there, too - sweet bean cakes, candied strips of coconut, and the thin-shelled lychee nuts, which were not nuts at all but dried fruit. There was nothing like it in American stores and we made them last as long as possible, which was not very long because Papa kept a stash of them in the storefront and stuffed handfuls of them into the pockets of children who had come to drop off or pick up their fathers’ starch-stiffened collars. “Here, put some in your pocket!” he would urge. “Good! Eat!”

My favorite was the red fire crackers, in singles or in long connected strings, which we could set off in the walled garden after dark, snap, crackle, and popping at our feet, the acrid smoke filling our noses. “Smells like China!” we’d cry. I also found the strange wooden rings and metal puzzle boxes that challenged you to take them apart and put them back together again, both irresistible and mystifying.

At the bottom was Papa’s own treat - a stack of black discs with bright orange centers, containing within their rings the music of his homeland. If he had restrained himself through the opening of the box thus far, the emergence of the records sent Papa up the stairs two at a time back to the parlor, where he fumbled with a new Victrola needle and, by the time we had all filed in behind him, had put the first disc on and turned the volume to full blast. The cacophonous clanging of Chinese cymbals and falsetto screeching of male opera singers made us plug our ears and giggle, while the cat streaked from the room. Our father, though, sat flopped in the sagging velvet wing chair with this hands behind his head, eyes closed, and face turned to the ceiling in a look of pure transcendence. Mama walked lightly to the Victrola and dialed the volume down, admonishing gently, “You can hear that all the way down to Bull Street, my darling. What will the neighbors say?”

We didn’t have much money, but it felt like we were growing up in a golden palace.

Our Gang

In August of 1923, we started at the public school. The kids there were curious. I took my seat in the front row on the first day and could feel their stares boring into me from all sides. I wasn’t nervous. Papa had told me that morning to walk tall, “Remember your name is Chan.” If I caught one staring at me, I looked him or her in the eye straight back until one or the other of us broke the gaze and smiled into our desk. Making friends was pretty easy after that.

I recognized more than one in the corridors as being among those who stopped by the laundry to drop off or pick up collars for their fathers, who were bankers, lawyers and judges, dry goods kings and automobile dealers. I soon found out that several of my classmates also lived within only a few blocks of me. This made it easy to fall in to a little impromptu group of friends after school that we soon started referring to as Our Gang - Will, Frank, and George were from my grade in school. Ned was older and should have been in one of the higher grades, but had been held back at least a year and he looked comically large in the school yard. Will and Frank’s fathers were a dock worker and a brick layer, respectively, and Ned’s father worked at the forge at Kehoe Ironworks. George’s father worked at Union Camp, a division of American Pulp and Paper Company.

Will was my first friend at public school. We some of us called him Wee Willie Winky to get his goat, but learned soon enough that we put our own hides at risk to do so because although he was small, he was strongly built, like a bull, and he acted like one too. He was square-jawed and pugnacious, but overall an outgoing and good-natured kid who was never really wicked, just wanted to have a good time. While I went to lengths to control my rooster tail and make sure my hair was always well parted and combed down, Will had a shock of wild curls he rarely took a comb to and chose to control mostly by wearing a baseball cap, always turned to one side. His clothes were often dirty and mine were never so. We couldn’t have been more opposite in looks or surface temperament, but we got on like gangbusters. We played jacks and marbles, stick ball in alley ways. We went to the Five and Dime for penny candy and loitered on the front stoop to eat it, butterscotches and peanut chews, caramel creams and bit-o-honeys.

One day, when we reached the store, there was an old Negro man sitting on the bottom step and leaning against the post. He was decently dressed, but his clothes were old and hung on him like maybe he used to be a much bigger man and had just… shrunk a little bit. But then I saw the way his ankles showed and figured maybe they were hand-me-downs. I fingered my own waistband bunched up under my belt and wondered what an old grandpa was doing in hand-me-downs like me.

He was dusty and grizzled-looking and needed a shave, but I could see by the way that he lifted his head as if to catch a breeze and looked in the middle distance when we approached, that he was blind. I reckoned you could forgive a man for not shaving every day if he couldn’t see what he was doing. He held a little tin cup on one knee and I stopped in front of him. I knew what the cup was for, but he didn’t ask for anything, he just looked almost-at-me and smiled. “Hey Mister,” I said, smiling back. I figured if he couldn’t see me smile, maybe he could feel it, kinda like the way he seemed to feel how tall I stood.

”Hello, child,” he said, waiting. And because I didn’t say anything, “It’s a mighty fine day today.” He turned his head to catch another breeze. “Yes sir, a fiiiiiiine day. You goin’ in to get yourself a cold drink?” Leaning in with an eager look cast over my shoulder. “A Coca-Cola?” I stared at my nickel, rubbing it between my thumb and forefinger.

“Nah, I was just here with my friend, gonna go get us some candy,” I said, although this was suddenly a much less delicious-sounding proposition to me than it had been.

“Candy! Oh now…let me see, I remember I always wanted to get the licorice…and them cracker jacks! Those were the berries. They came with a toy surprise inside,” he chuckled at the memory.

“I like the butterscotches,” I said. “And the peanut chews - dark!” Will was standing impatient in the doorway, waving at me to come on. I dropped the nickel in the man’s cup and followed Will inside. “What’d you do that for?” asked Will, a little put out, as if it had been his nickel I’d dropped in the cup.

“Bless you, honey,” called the man, through the screen door that slammed behind us. “Bless that child,” he said again to himself.

“I don’t know,” I said to Will. “I just felt like it. I’m not hungry anyway.”

“Who said anything about ‘hungry’?” said Will.

Will and I played hide and seek in the park and ran races on stilts made out of tin cans and twine. I never laughed so hard or had so much fun in my life as I did with him.

On Friday nights, I took to going to bed fully clothed so that on Saturday mornings, Will could swing by the laundry early, and tug on a piece of string I tied to my big toe when I went to sleep and dangled out the second floor bedroom window. I felt that tug and my eyes flew open as if I had been waiting up all night, and I unhooked the loop from my toe, jumped out of bed, grabbed an apple or a slice of bread from the kitchen, and ran downstairs, ready to embark.

Will had a lot of friends. Some of them I liked and some of them I didn’t as much. It was all the same to Will, though. You know the sort. If he could have a good time with you, you were in. Ned was one of the ones I didn’t like as much. He was older by at least a year, maybe two. Big, blunt-nosed, sometimes surly, his hair and body bristled like a baboon with a toothache. He liked to pound a fist into his palm whenever he got to talking about someone or something he didn’t like, which occurred pretty much daily. He wasn’t aggressive toward me, not really, but I know I confounded him. He often addressed himself to everyone else in the gang and simply pretended I wasn’t there. I suppose we tolerated each other because we both wanted to remain friends with Will. I had never really had playmates my own age before, and I was eager for it to continue that way.

George was another of Will’s friends. He was tall and lanky and I liked him a good deal. But he walked, even at age 10, with an old man stoop in his shoulders, like he was trying to shield something precious and delicate against his chest. This gave him the initial impression of being chicken-chested, but he wasn’t. To tell the truth, I kind of felt sorry for him. George’s father sometimes turned up at the school yard in the middle of the day, disheveled and belligerent, alternatively trying to coax and command George to come speak to him through the fence. George usually saw him coming before he got there and would spin his back to the road and make as if he couldn’t hear, but eventually his father would kick up such a fuss, pacing and calling out and sometimes rattling the fence, that George would have no choice but to go to him. I can still see him standing there, stock still, hands in his pockets, looking at his feet while his father’s voice, indistinct and wheedling, sometimes angry, carried on the breeze. George slightly nodded or shook his head in response and when he finally broke free, trudged back to the school yard, chest even more hollow than usual, shoulders hunched up around his neck, and more often than not, in a foul mood and liable to lash out. I could see why that might be the case. Try as I might, it was impossible to imagine being ashamed of Papa.

When George spoke, which was not all that often, he tended to fidget, and looked compulsively down and away, or rolled his eyes dramatically up to the ceiling, as if eye contact was physically painful for him. One on one, though, he was a pretty good egg. I could also see he couldn’t stand Ned, probably knew his type, and since I had pegged him for a big dumb bloviator myself, that tacit understanding became part of George’s and my budding friendship.

Finally there was Frank. Frank was little like Will, but without the big personality that demanded you forget it. He kind of went along with whatever the gang was up to, but fed off the momentum we had going on, and was like to go too far with it, and ruin the fun. After that he’d usually fall into a despondent funk of self-excoriation, which was tiresome in its own way. If we were playing tag, he’d end up tackling you and knocking your teeth in the dirt and suddenly the game would be over. Or if we were swimming in the river and splashing each other, he’d try to dunk you and hold you under and we’d march, coughing and spluttering, in sodden disgust back up the river bank with him scrambling behind us. “I’m sorry, y’all! I didn’t mean it! I was just trying to have fun! Come on, don’t go, don’t leave! I won’t do it again, I swear, scout’s honor!” But then we’d go for cones or something and we’d get into some good-natured jostling, and Frank would ram someone hard enough to knock their ice cream in the dirt, and so it went.

Everything was copacetic except that I did make the mistake of telling them my sister called me Oil Can one day, and the name stuck. Ned found it particularly funny and it was one of the only times he spoke directly to me. “Yeah, ‘cause you look like you fell in a vat of oil! Hey, Chinaman, you’re oily, you better wash that off!”

“No, dummy,” said Will. “It’s his name. Earl? Oil….? You get it? Chan? Can….? Gee, you’re none too bright are you Ned?” Ned drew himself up and started punching his palm, but Will was untroubled. I looked down at my hands and saw them, maybe for the first time, through someone else’s eyes. Then I looked at Ned and thought, if anyone had asked, and they hadn’t, that he looked like something that just crawled out from under a rock. I put my hands in my pockets and wandered off to gather chestnuts for my slingshot. When I picked the next one up and husked it from its spiky shell, revealing the deep swirls of brown and amber tones and a smooth gloss that mesmerized, I couldn’t help but notice that it was the exact same color as my hand.

An Unexpected Visitor

One day a boy named Jimmy turned up at the river. He came upon us sitting on the bank, trying to make fishing poles. I had my whittling knife out and was trying to demonstrate to the other boys, who were seated around me, how I had smoothed a branch for my bow and arrow, and how to tell the best kind of branch for it, not too stiff and not too soft. I was getting ready to demonstrate the piece de resistance, how to notch the end to facilitate the attachment of the line, when Jimmy sidled up to the group said, “You don’t have to do all that, you know.” My annoyance at being publicly contradicted soon turned to curiosity when I saw his face - open, helpful, matter of fact. My hackles smoothed. “How so?” I asked.

“See?” he said, pulling something out of his pocket and holding it out. “Look at this.” It was just a wooden dowel, about the width of his palm, with string knotted around the center and wrapped in a thick coil all around. He had a hook tied to one end and a little lead sinker, and a tin can full of earth that he kept worms in. “It's called hand line fishing. My daddy taught me. We get catfish around here, large-mouth bass, bluegill…. on the regular. My grand-mama fries ‘em up on Sundays.”

Jimmy had red hair, cropped close and mostly hidden by a baseball cap. He was the first redhead I had ever seen up close and I couldn’t help but be curious and stare at him the way my classmates had stared at me. His eyelashes were thickly curled, growing in deep auburn at the root and lightening to yellow at the tips. They rimmed dark and earnest eyes the size, it seemed to me, of mama’s cookies. It was an arresting combination that made eye contact hard to avoid and easy to hold - even for George. Jimmy was quiet but not particularly shy, and I liked him immediately. He didn’t go in for all Ned and Frank’s hokum and was untroubled by Will’s direct and challenging nature, but nor was he beguiled by it either. I started to think he might mainly be hanging around for me, which made me feel pretty good. He didn’t go to school with us, but he started turning up for our after-school capers on a regular basis, and eventually, almost daily. He was calm and easy-going, what we called “copacetic,” and balanced our group out well I thought. We often met at the river, but you could catch us pretty much everywhere, sometimes even taking the streetcar to the edge of town, downriver, and wandering around in the sticks, where the insects grew louder and the vegetation closer, Spanish moss hanging in great sheets over our heads.

The Dead Girl

There were old plantation homes out there, several of them having seen better days and at least a couple that were abandoned and falling to ruin. Gerald said they had probably been burned by General Sherman during his storied march to the sea. At any rate, we traipsed into the overgrown lands and had a grand old time tip-toeing across rotting verandas, peering into broken windows. We gaped at the rain-soaked, dismal and crumbling remnants of impossible luxury - dusty chandeliers, broken mirrors, shattered glassware strewn across the floors, soot and mold licking up the walls, splintered balusters. A thick layer of grime lay over everything, piles of leaves banked in the corners, and animal droppings evidenced the new inhabitants everywhere we looked. It gave us the heebie-jeebies and we loved it. We also scurried around the grounds and played hide and seek in the slave row and the once-elegant landscaping gone to seed, which created all sorts of secret and hidden spots.

One day, Will’s voice called out from a distance. “Y’all quit hiding! You gotta come see this! You hear me? Come out!! Come see! I’m over here!” I crawled out from under a thick curtain of rhododendron two stories high and followed the sound of Will’s voice to a back corner of the land, where he was standing under an enormous magnolia, next to a rectangular structure that, upon closer inspection, revealed itself to be a family tomb. The stone was covered in algae, and masses of ivy grew at its base; decades of rain and weather had worn the details down to indistinct lumps, but I could still make out two fat cherubs floating on either side of a central crest with the family’s name on it: MANIGAULT.

But what Will was pointing to was not the tomb itself but something next to it. We drew closer and peered around the side to where he was looking, and saw that the door to the crypt had been broken, and a cast iron casket was protruding almost in its entirety, as if someone had tried to drag it out but given up and simply dropped it, feet still up and inside the crypt, head down and on the ground. Hot, spidery prickles shot all up and down my spine and crawled up my scalp. I was suddenly very aware of my own heartbeat in my ears and my breath, which was coming quick and hard.

This was no ordinary coffin that I had seen, but cast into the shape of a shroud, the details of the “folds” clearly visible on the surface, appearing to “wrap” and “drape” in awful manner. I thought of the mummies in Mrs. Latimore’s dining room and felt my knees wanting to buckle. More astonishing still was the oval plate glass that was fixed over the head, where the face should be. We leaned in to see what we could see, and, with great cries of fear and loathing, leapt back as one. “I’m gonna upchuck!” yelled Ned, wheeling out of control and trotting to a halt well outside the circle of shade cast by the magnolia. He broke into laughter and bent at the waist, dramatically gripping his belly, to continue his pretended retching. Will, George and Ned ran around in circles trying to wrangle each other and force first one then another to come in close for another look. “NO! You think you’re the Big Cheese around here, you go!” said Ned to Will, dodging his grasp and spinning away with surprisingly fancy footwork.

Meanwhile, Jimmy and I hadn’t left the spot to begin with. We were rooted. The last thing I felt like doing was all that hootin’ and hollerin’. We stared at each other over the coffin, he on one side, I on the other. We both slid our eyes back down to see, and then suddenly, I fell to my knees and leaned right over to get a good look in the face window. I could feel the warm moisture of my own breath bouncing back to me.

She looked like she was sleeping, head resting gently to one side. There didn’t seem to be anything dead about her. I raised my hand instinctively to the glass as if to tap on it lightly and see if she would wake, but let it hover there motionless instead. I guessed she was about my sister Bernice’s age, six maybe seven. I turned my head sideways to get a better look at her. Her cheeks were still chubby and pink, her eyes lightly closed. Her blond hair was parted in the middle and done in tight ringlets, with a pink bow fastened above the curls on each side.

“How long do you think she’s been here?” asked Jimmy in a half whisper.

“I have no idea,” I said, “but I’ve never seen that hairstyle.” I looked up at him. “You?”

“No,” said Jimmy. “She could have died fifty years ago. Seventy five!”

I looked back down at her. The little Manigault girl, maybe old enough to be someone’s grandma. I could see her kneeling by her bedside, her little hands clasped fervently beneath her chin.

Now I lay me down to sleep,

I pray the Lord my soul to keep.

If I should die before I wake,

I pray the Lord my soul to take.

I didn’t tell Mama or Papa or anybody about what we had seen that day. It was our secret and brought our gang closer together I thought. Dead bodies can do that, I guess.

It took us some time to build up the courage to return to the Manigault house, and when we finally did, we discovered that someone else had found her too, but these were vandals. Someone had cracked the face plate with a rock. The little girl’s flesh, which had been so pink and plump, had now, in a matter of a couple weeks, grayed and caved in on itself. Her eyes were withered in sunken pits, and her mouth was beginning to pull back in an ugly grimace, showing her little teeth - white like a picket fence. It was foolish to think such magic could last. Some people just see a good thing and want to wreck it.

An Initiation

By October, our gang had settled in to a well-worn routine. Riverbank meet-ups, fishing, swimming, rambling, roving, ice cream treats, games of tag. We knew how to get each other’s goat, and mostly enjoyed doing so. George’s mood had darkened considerably since the summer though. His father had been fired from the Pulp and Paper Company, and when George came humping along with shoulders up around his ears and a deep frown on, we all knew to give him some room for a little while.

It was one such day that we were kicking pebbles on a country road outside of town and had fallen into a natural game of tag. George had arrived last and looking disheveled and surly, but we could feel him relax a little more with each hundred yards we left town further behind. It started to feel safe to drum up a little fun. Jimmy was “it” and it was all a good time until he tagged George, in what George felt was an unfair manner because he had been blocked from dodging the tag by a tree that “got in the way.” Now, obviously, a tree can’t get in anyone’s way, Jimmy reasoned. “A tree has roots and doesn’t move. You just ran into a tree!” he said, snickering. “That’s a whole other ball of wax! I tagged you, you’re it!”

“I’m not it!” said George.

“Yes you are,” said Jimmy, “you’re cheating!”

“I’m not a cheater!” said George, seething. “Take it back.” I had never seen George be the aggressor; gee, that was what the shoulder hunch was all about - shielding himself from a bad situation, not causing one. But something inside him must have broke because all of a sudden he lunged at Jimmy with bared teeth and a growl that was pure animal. Jimmy was quick and light on his feet, but George was tall and his reach was long. It wasn’t but a few seconds before he grabbed Jimmy by the back of his shirt, ripping it from his waistband, and swung him around like a rag doll and the fight was on. They grappled with arms locked around each other’s shoulders, peeling at each other’s fingers and each trying to reach down and grab the other by the knee or ankle. George finally got a hold of Jimmy by the belt and swung him hard in an arc, out and away, grabbing the ball cap off his head as Jimmy skidded into the dirt.

Jimmy landed on his elbows, knees up, and stuck there like a statue. His stillness was preternatural, almost like he was summoning some protective coloration, like a chameleon, like he was lying there trying to pass for a rock or something. Only his chest heaved up and down, and I thought of the mouse I cornered once in Mama’s kitchen with broom and bag in hand - tiny, still, and gasping. George had staggered backwards a few steps and had Jimmy’s ball cap in hand. He continued to scowl, open-mouthed, but the spell was broken. We were all frozen in our respective places.

Jimmy’s hair, normally hidden under the ball cap, now stood up in unmistakably stiff and woolly peaks. His eyes, dark and vulnerable, scanned our group and found mine. My insides had turned to liquid. Was he waiting for me to say something? I could hear his voice in my head, with just a hint of a question, “Earl…?” I opened my mouth and closed it, like a fish hauled up on the river bank and left to gape. I licked my lips because my mouth was dry and then, because I couldn’t bear it, I broke the gaze. I looked at my feet and instinctively shuffled backwards, heat rising painfully in my chest.

I looked to the side and saw Will squinting with cocked head, like he was considering a bug in a jar. Frank giggled nervously.

It was Ned who broke the silence. “Well, well, well, lookee what we got here, boys,” he cried in glee. His voice, which was entering the early stages of puberty, sounded more abrasive than usual, serrated even. “Looks like Jimmy here’s a nigger!” He laughed raucously in disbelief and said it again, “Jimmy, how come you never said nothin’ about you bein’ no nigger?” I flinched inwardly and shoved my hands deeper into my pockets.

George looked down at the cap in his hand and frowned, confused almost, and tossed it at Jimmy’s feet. He turned and ambled away, rolling his eyes up to the sky and shaking his head almost imperceptibly. He hadn’t meant for things to get out of hand like this. I could see that. I also knew that a rock in motion stays in motion, until and unless somebody does something to stop it. Who was going to stop it?

Jimmy reached cautiously for his cap, never taking his eyes from us, and gave me a last, lingering look. I managed to stare back at him but found I could say nothing. I ducked my head and took another step back. At that, with hat in hand, Jimmy scrambled to his feet, turned tail and ran, as fast and as hard as I ever saw a boy run, all elbows and knees, shirt tail flapping, never looking back.

“Run, nigger, RUN!” yelled Ned, throwing a pebble after him.

“Yeah, SCRAM, nigger,” shouted Frank, who seemed now finally to have found his part to play. I looked over at that little pipsqueak and saw him for the sorry sidekick that he was. But then what did that make me? What does that make you, Oil Can?

Willie Chin & Co.

I hung my head and scuffed my Chuck Taylors in the Georgia dirt, turning them a deep dusty yellow at the toe, which faded back to brown at the back. I kept my eyes on my toes, not thinking too much about what had just happened, but not able to think of anything else either. My mind was empty, my ears ringing. I clicked my teeth together in absent-minded patterns, sliding them side to side, listening to the light scraping sound of enamel on enamel. Nobody said anything much after that, and I walked well away from the group anyway.

The boundary between dirt road and cobblestone was abrupt. You could see yellow sand sprayed out in amongst the cobbles and knew you were back “in town.” We got to the turn off, where Will, Ned, and Frank, who all lived in the same neighborhood, had to go in one direction and I in the other. George had peeled off some time earlier to places unknown. The atmosphere was subdued. Even Ned seemed, if not contrite, then at least sorry that all the fun had been ruined and annoyed that everyone seemed to be blaming him. “Bye, Earl,” the boys muttered, not quite in unison. “See you tomorrow?” I gave a half-hearted flap of the hand over my shoulder as I turned toward home. In fact, I didn’t see them tomorrow, nor the next day either. The magic was gone.

The Willie Chin & Co. laundry storefront was on Whitaker Street. Papa had started as the “& Co” when he first arrived, after a failed attempt at running a restaurant, and then bought the place outright when Mr. Chin retired and returned to China. The name, though, stuck.

Papa kept the sidewalk in front swept sparkling clean, but I came in the back way, along a dirt alley bursting with weeds. Broken shards of glass, rotten bits of wood, rusty nails, and bits of old roof flashing accumulated at the base of the buildings and crunched underfoot if I left the center of the path, which I did, for it was mucky with poor drainage. I kicked a sodden shoe that lay on its side out of the way and when it rolled over, landing on the upper, noticed a large hole in the sole. Papa was always complaining about “not ver’ much money” but one thing he never did was let us have holes in our shoes. “Your name is Chan,” he said, as always. I was suddenly unsure that I knew what that meant.

Pushing open a weathered wooden gate door about seven feet high, I entered the walled, dirt-swept courtyard behind the laundry. There was a dilapidated lean-to to the left, inside the gate, filled with old buckets, scrap wood, barrel hoops, crates, broken furniture, old broomsticks. A mildewed brown blanket was thrown carelessly in a heap on top, for reasons unknown. The door to the laundry room was open to help circulate air. It was hot as blazes in there, even in October.

I looked to my right and saw Charley, the laundry foreman, on his break, sitting on one of the lower steps that led up to the second-floor residence, above the laundry. He had one knee up and was resting an elbow on it, dangling his hand limply with a hand-rolled cigarette smoldering between two fingers. Charley had plenty of gray hair by this time, but his arms were smooth and muscular like a man’s 20 years his junior. His once-white shirt was a dingy, sodden brown, open halfway down his chest, with sleeves rolled to the mid-upper arm. It was a comparatively cool day for October, but his dark skin glistened with sweat right down to the backs of his hands.

I shuffled toward the stairs to head up to the kitchen. Charley had been eying me since I walked through the gate. I didn’t feel like saying hi and wasn’t even going to ask him to move. I put my hand on the rail and made to squeak past him when he broke his silence.

“Hey, boy,” he said with a chuckle in his voice, “what you lookin’ so glum for?”

I slid my eyes up to his and pursed my lips in a tight smile and looked down again.

“Aww, it’s nothin’,” I said and went up the stairs. I could feel him turn to watch me and felt his eyes on the back of my head, which prickled, but I didn’t turn around.

I’d known most of the people who worked in Papa’s laundry my whole life, but Charley was a special friend of mine. He had helped me make my own handline fishing dowel like Jimmy’s and even upped the ante by showing me how to tie a fly to the hook and telling me the best holes to go to. Charley was friendly with all of us kids – my two brothers and three sisters – but there was a special twinkle in his eye for me. He called me a little scrapper and bust out laughing at a lot of the stuff I did and said. Mama might be exasperated, and Papa mad, but Charley was always just amused.

His favorite story to tell, and he told it often, was how, when I was a little boy – maybe three years old – whenever I got sick of the “church ladies,” as he called them, coming over and taking up Mama’s time, I would take that little wooden chair – “that one right there,” he’d say, pointing to a chair whose seat was shin high, still sitting in the corner of the courtyard – and “throw it…down…the stairs! And then what you think, that boy start cryin’? Like it was him that went tumblin’ down, and Miss Annie would come runnin’.”

Charley would break up then, both legs off the ground when he laughed and typically had to stamp it out when they came back down. It was kind of contagious. I got to thinking that sometimes he was just looking for something to laugh about, though, because the stuff that made him roll around wasn’t even always that funny. Sometimes it was, and sometimes I got the feeling that he just felt like things had gotten too serious for a spell. When he recovered himself, if I was in striking distance, he’d grab me and ruffle my head or give my bottom a friendly smack and sum it all up for everybody, the same way every time, “Look at Robert Earl. This boy knows what he wants. And knows sho’ ‘nuff how to get it too!” Like I said. Amused.

However, there was one time when I opened Papa’s large black umbrella and jumped from the second-floor balcony roof, imagining that I would float down like I’d seen in the moving pictures at the Palace. But what happened was that Mama saw me fly past the kitchen window like an anvil. Naturally she came running, but it was Charley who got to me first. He found me bruised and winded in an azalea bush, and his eyes weren’t laughing then.

He said I reminded him of his boy.

“Where is he?” I asked one time.

“I don’t know,” he said, straightforward, simple.

Sometimes, I had to sit in the laundry all day on a stool next to the water gauge, checking the temperature and making sure it was always where it needed to be. It was the worst. All of us had to work in the laundry in some way or another, except Bernice, who was still too little. Archie was the oldest and had to do almost everything Papa did, and some stuff he didn’t do anymore – like mucking out the stables for the horses and hooking up the wagon for deliveries. Sandor apprenticed with Archie, so they were gone for much of the day. Gerald and SinFah were in the front, welcoming customers, taking orders, writing out tickets.

Actually it was Gerald who ground the ink and used Papa’s calligraphy brushes to swipe bold numbers on the ticket papers for customers. She worked the cash register too because she was responsible and good at math. SinFah, on the other hand, flitted around the store, pirouetting and practicing her small talk, making eyes at the young men, and falling in to a morose pout when the store was empty again. If she ever had to do “the work” out there, the aggrieved sighs made it so miserable for everyone that she was eventually relieved of her duties and she could happily return to her plies and glissades, her “Well I never”s and “I do declare”s.

I had a good view of these antics from my stool in the back laundry room, because it was near the doorway that connected the front to the back. From my distance and isolated duty, I could laugh. Sinnie was a pain in the butt. Charley would talk to me like a man when I was back there, though, and let me hand him the wrench while he was fixing laundry tubs.

Another day he had heard me yammering about cousin Wing (who is not really my cousin; our fathers just come from the same village) getting a BB gun and not too long after, he took me out to the courtyard and handed me a long object rolled up in newspaper. He squatted down and brought it out from behind his back, checking over his shoulder to make sure no one was looking for him out the back door. Then he turned back to me with an eagerness I hadn’t seen before.

“What is it” I asked.

“Why don’t you take the paper off and see,” he said. I unrolled the thing and felt my breath hitch in my throat. I looked up at him with eyes wide.

“You got me a BB gun?” I said, dumbfounded.

“Yeah,” said Charley, ducking his head in a nod, his eyes searching my face for something. “What you think?”

“I love it,” I said, still a bit breathless. I ran my fingers over the rich red grain of the wooden stock. I turned the gun up and looked more closely at the oiled black metal, then closed one eye and peered into the barrel. Charley ripped the thing out of my hands, startling me.

“Never point a gun in your own face,” he said sharply.

“It’s not loaded though is it?” I said.

“You don’t know, do you?” Charley continued, “Never point a gun at anything you don’t intend to hit.” He hesitated for a minute to satisfy himself that I had heard, and maybe to ask himself if he had made a mistake. I began to squirm under the intensity of his gaze. He handed it back to me. “You gonna go hit some targets with Wing now?” he asked.

“No,” I said. If Charley was surprised, he quickly hid it.

“Why is that?” he asked. I told him,

“Well, Wing’s daddy broke his BB gun over his knee a couple days ago and then stomped on it and kicked it down the stairs because Wing shot his sister in the butt.” Charley, who was still squatting at eye level with me, hollered enough to make me jump. I started laughing too, and soon enough, couldn’t stop. Charley eventually stood up, leaned on his knees, and gave my bottom another smack and told me to go on and git. “Go set up some cans, then, and get shootin’.” I ran out the back gate into the alleyway and could still hear Charley laughing as he went back into the laundry to work.

I kept that BB gun for many years. Turns out, I’m a crack shot and I never aim at anything I don’t intend to hit.

So it was all Charley on my mind when I went in the door at the top of the stairs and entered the kitchen. I was feeling mighty low. Mama was bending over to get some cold ham out of the icebox for lunch and I slid sideways into a chair at the table, in a slump. Mama dropped the ham on the cutting board on the counter and reached for a carving knife, looking quickly over her shoulder to make sure nothing had happened.

“Mama, are we niggers?” I asked. The question felt coarse and unpleasant on my tongue, but then, I was feeling coarse and unpleasant.

The sound of the knife clattering in the enamel sink jolted me out of my churlish reverie and snapped me back to the present, and it wasn’t one I recognized. Mama spun around and steadied herself on the counter behind her. I had never seen her like this and knew immediately I had made a mistake. I leaned back in consternation and moved my mouth a bit, but nothing came out - speechless for the second time today. Her mouth was pursed and her chest heaved. What scared me the most, though, was her cheeks flushed a violent blotchy red that went right up to the rim of her eyes, which were blazing.

Mama was not a screamer or a hitter. Papa, despite his generally good nature, could hit, and hard, but Mama was gentle, and hardly taller than myself. Even so, I was in uncharted territory at the moment and didn’t know what to expect and the waiting was agony.

After a moment, though, she had reached either some place deep within herself or high above herself and reigned her high emotion in, for she restrained herself to a simple, quiet statement: “All people are children of God, Robert Earl.”

In the silence that followed, and by way of explanation, I told her what I had seen. She listened without interrupting. But when I was done, she didn’t say anything. She went back to the ham on the counter, picked up the knife, hesitated for a second, put it back down and then hissed over her shoulder, “We are not Negroes. Go back outside.”

Soon thereafter, the newspaper man came to our school to snap our picture.

The Third Rail

The third rail, in writing, is like the actual third rail on a train - the (usually hidden) source of electricity, which drives a story forward and which control’s a protagonist’s worldview and actions without their knowing it. It is almost always based on a fundamental “misbelief” that the protagonist has about how the world works and used to be called the much more scary- and irreparable-sounding “Fatal Flaw,” but that’s unfortunate because it is not fatal, or at least, it doesn’t have to be. We all have one (or more) such misbeliefs and we all spend our lives overcoming them. That’s what human life and growth and development are about.

Misbeliefs are almost always incurred during early childhood and can be a single event or a series of circumstances, but they are discreet and bounded, and soon step into the driver’s seat of a person’s life - staying there until and unless he or she can come to rights with it. If you excavate your character (or yourself) carefully, you can figure out

1) what the main misbelief is; and, therefore,

2) where it likely sprung into being and took root; and finally

3) how it challenged your character and promoted either growth or failure at key points throughout their lives.

You have to understand what your character’s misbelief is and where he got it before you can write the story, because when the character enters your book on page one, he already has this misbelief in place and is being driven by it. What is more, the writer Lisa Cron, in her book Wired for Story, points out that the protagonist doesn’t know he is wrong, and actually mistakes the misbelief for a valuable piece of “hard-won and savvy intel,” and the key to getting what they really want in life. The irony is that it’s more likely to be the thing that drives them off a cliff. But therein lies the story, do you see? Will he ever realize the misbelief for what it is? Will he ever come to rights with it? Or will he be driven by the third rail forever?

This blog post was about unpacking what Dad’s misbelief was and where he got it and what it cost him to struggle with it. From my writer’s notebook, a scribbled brainstorm about Dad’s Third Rail:

A mixed-race boy in the Jim Crow South thinks he must be twice as good as anyone else to get half the love. This unspoken anxiety creates a compulsion to control the world around him and his own destiny. He proceeds to spend the next 100 years bending the world to his will, attaining impressive achievements, and conducting shocking feats of derring-do that lead many to remember him as “almost magic.” Moral injury in war contributes to feelings of unworthiness, and destroys his relationship with his son who has his own misbeliefs. Ultimately, he discovers on his death bed that control is an illusion, he must let go of grudges and disappointments, and that he has been worthy all along. He reconciles with the youngest child, lets go the need to with the oldest, and deepens his connection with the middle. He crosses the threshold from control into command and soon thereafter releases himself to death.

How did this happen? Where did it begin? I argue that it began with a social experiment and on the banks of the Savannah River in 1923.

*n.b.: this has been a fictionalized account of true events. All the key plot points described here are historical facts: Dad and his siblings did have a home tutor they didn’t like, and a tutor across the park that they did; they did enter white schools in 1923; they did get profiled in the paper; the laundry foreman was named Charley and he did give Dad his first BB gun; Dad was part of “Our Gang” and one amongst them was “outted” as being black and never seen again; Dad’s mother did get cagey about her past which was, as we learned decades later, because she herself was 1/3 black and actively trying to protect her family by passing. The fact that Dad worried these tales in his pocket for the next 90 years does show their emotional and moral impact on him, and makes them a good candidate for the origin story of his own fundamental misbeliefs. That all said, certain names, and details of events and conversations have been filled in and fictionalized. In places where I didn’t know the literal truth, I have tried to feel my way into a space that is emotionally true, and consistent with the major plot points and the characters of the story.

As I am writing a memoir, however, and not a biography, it is I who am really the central protagonist. And so it remains for me to write my own misbeliefs and origin story, and to find the points of contact and interaction between mine and his. Coming soon….

Like, Comment, Share!

Although the buttons below work, Squarespace is currently struggling with a bug that erases the tracking at random. Please don’t let low or no numbers shown deter you. Likes and shares still help boost my visibility, even if the numbers don’t stick around to show it. Thank you!